Reforming Children Through Isolation And Brutality: Kaduna Borstal’s Harsh Methods

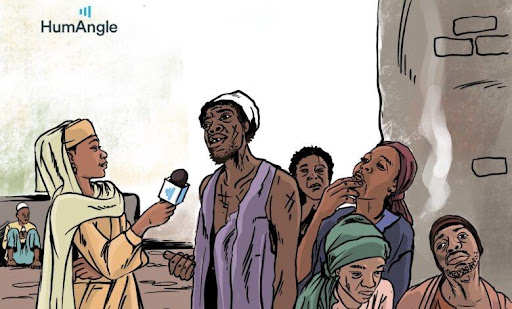

The borstal training institution in Kaduna, Nigeria, boasts of having reformed delinquents, child offenders, and drug addicts. But what methods are being deployed to achieve this? HumAngle investigates.

There was the fact that he stopped attending class at his secondary school and preferred to pass the time by the roadside with like-minded friends, doing drugs and chasing after women. There was the fact that he was merely a teenager and was already so far gone on his way to destruction. But there was also the fact that he was beginning to steal millions of naira from his family to fuel this lifestyle.

That was where his parents drew the line.

Having tried all kinds of admonishments and failed, they panicked, fearing that they were missing an opportunity to reverse an unfavourable course of life for him that was day-by-day inching towards the irrevocable mark. And so they arrived at the decision to commit Muhammad* to an institution famed for its brutality in the hopes that it would reform him.

Upon arrival at the Borstal Training Institution in Kaduna, northwestern Nigeria, that day in 2015, he was committed to a place he describes as a dungeon but known at the institution as the “Black Cell”. There, he was in total confinement for weeks. There were others like him in similar conditions.

Total Confinement

The Borstal Training Institution, which started operating in 1962, was established by the Borstal Institutions and Remand Centre Act of 1960. It exists to reform delinquents, drug addicts, and child offenders, mostly between the ages of 16 to 21.

They employ techniques that range from counselling, spiritual aids, and according to past inmates, dehumanising behaviour.

“It was very bad,” Muhammad tells HumAngle. Everything about the Black Cell was unbearable, from the total confinement to the treatment they received from some staff members, which he says seemed designed to break down their resolve and generally dehumanise them.

But most unbearable of all were the flies and the lice. The cell had all kinds of flies that never left him alone. At some point, lice began to hatch on his bare skin.

“It was total confinement. You can’t even see the Sun unless maybe they open up the place for people to take a bath or use the toilet. That’s all.”

The experience is similar to those recounted by people who have had to be confined at torture houses known as Gidan Mari across northern Nigeria to rid them of drug addiction.

But even these torture houses have since been declared illegal and shut down. Still, residents of places like Kano say they remain in existence.

Asked about the Gidan Mari methods, Musa Dauda Doguwa, the controller of corrections and principal of the borstal institution, was quick to try and distance himself from them. He said it was a terrible way to reform addicts and that they would only come out more hardened.

“It will even make the child hate the parents for taking him there,” he said. He did not directly address the specific ways the institution treated drug addicts or the practice of total confinement when asked.

Drug Abuse Rife

According to Emmanuel Paul Asan, a clinical psychologist with Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Hospital, Bauchi, total confinement for drug addicts is usually done to limit their drug access.

“In confining the person, the patient experiences withdrawal symptoms, such as stomach cramps, insomnia, dreams, restlessness, etc. All these are cravings … confinement is good. Sometimes, confinement comes with psychoeducation and cognitive behavioural therapy to create awareness in the patient,” he said.

However, Muhammad says that the confinement he and others went through was bad enough to make some lose their minds.

He says he was often filled with thoughts about the outside world, knowing that he would not have been subjected to that level of harassment if he were not detained.

Drug abuse in Nigeria is rife. According to a 2019 study, 14.3 million people aged between 15 and 64 years are engaged in the use of drugs like cannabis, codeine, morphine, and others.

Three months in to his ‘treatment’, Muhammad was finally removed from the cell and transferred to the ‘yard’, a place that functioned more or less as a dormitory, and he was categorised under the grade of inmates known as ‘junior boys’.

The difference between the yard and the dungeon, he says, was the chance to go out into the compound and move around. He was also finally able to have access to the psychologists, sports, and literacy programmes the institution ran for students.

But even that did not completely make up for the other experiences he continued to suffer. For example, like other junior boys, he was required to wake up every day at 4 a.m., sometimes even at 3 a.m., and head straight to the lavatory to wash it with his bare hands.

“It was very irritating. You have to do it with your bare hands. Sometimes you even have to pack shit,” he remembers, describing how they were ordered to dig out the latrines. “And many times, there was no soap.”

After that, he had to do chores such as laundry.

Senior boys

But the most humiliating part for him was how he was always treated and talked to in a derogatory manner by those referred to as “senior boys”. For example, if he woke up at 4 a.m. as was required, he had to walk as soundlessly as possible out of the dormitory because if he so much as coughed or made a sound that woke a senior boy up, the entire yard would be subjected to all kinds of punishment that usually culminated in a general beating.

“There was nothing they hated more than being woken up,” he said of the senior boys.

There was also the fact that whenever they received foodstuff and provisions from their parents during visits, they could not keep it to themselves, as they were waylaid and forced to hand it over to the senior boys.

“If you don’t hand it over to them, they will forcefully take it and still beat you up for it.”

Staff play down the harsh conditions. The head of academics, who identified himself only as Bitrus, said the treatment juniors received from their superiors was typical of boarding schools in Nigeria, citing examples from his own experience.

“During our time, if a senior shouts for a boy to come, we would have to run towards him so that he won’t get angry and punish us.”

Perhaps because of this lackadaisical attitude, Muhammad said reporting these injustices to the administrators was not always possible because, in addition to nothing beneficial coming out of it, you would be labelled a ‘witch’ in the yard, ganged up on, and beaten. You would also be ostracised.

“Even the staff are merciless. So you can’t even complain … In the yard, they will point at you when you’re walking past and call you a witch. Then they will gang up on you and start slapping you anyhow. You will hate yourself so much that you will wish for death.

“You may not know from the outside. But all kinds of things are going on there. I knew junior boys who used to eat rotten food from the dustbin because of hunger. There was hunger in that place.”

Is the approach working?

Muhammad feels like the approach used at the institution is necessary and helpful.

“The things that go on there, they are things that you know can never happen to you in the free world, so when you go back to the free world, you won’t want to do anything that will take you back,” he says.

Asan, the clinical psychologist, also explained that drug addiction treatment could be done through either ‘the carrot approach or the stick approach.’ However, the use of dehumanising approaches in treating addiction can be counterproductive.

“The violent approach only hardens the user. It also makes them develop low self-esteem, which is a factor for an increase in drug use.”

When we reached out to Femi Babafemi, spokesperson of the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), on whether the practices at the institution are appropriate and acceptable to the Agency, he replied, “That’s inappropriate if true, but we’ll investigate.” He further assured us that the Kaduna command would be in touch with further details as they investigate.

Rape

Muhammad spent two and a half years there, across the dungeon and the yard, as a junior and senior boy. There were many bad experiences, but the one that stood out were the rapes; the cases he witnessed of men raping boys, even in the presence of other junior boys.

Still, he insists he came out of the institute a better person than he went, especially because of the other literacy programmes.

The literacy programmes the centre currently runs are done in collaboration with organisations like the Yasmin El-Rufai Foundation (YELF), and they seem to be impactful. Book readings are held, and the authors of books the inmates have read are invited from time to time to hold interactive sessions with them.

One such author is Su’eddie Vershima Agema, a renowned Nigerian poet and novelist. Agema says he was there in March this year.

“What I did, on the one hand, was a workshop, and an interactive session on the other hand,” he says. “Surprisingly, they did more of the talking; all the interpretation of my work. I was mindblown. It was very impressive. One of them came to me and said what I had written had filled him with hope and let him know that he could be better, that he has a future.

“The conversations we had there could have qualified as a workshop anywhere in the world, even in England. I’ve travelled to England and different countries to give workshops, and I dare say that was one of the most intellectual, engaging, and beautiful engagements I’ve had.”

Agema admits that the administrators did say that they sometimes used “unorthodox methods” to treat “hardened inmates”. He did not ask what those methods were.

Is it working for everyone?

When Shafa and her family first entered the premises of the borstal institution to visit her brother Braima* she was consumed by a feeling of dread, even before she saw him. There was something about the place that made her feel tense and restless.

“I can never forget how I felt the day I entered that place. It felt like a place of doom. I felt scared; I felt worried, even before seeing him.”

When he was eventually led out into the compound, Shafa’s heart sank, and she began to weep. He looked so dishevelled, his body covered in welts and scars. He would also not look her or her mother in the eyes. The man who led him to them talked to him with a lot of derision, “as though he were talking to an animal,” Shafa recalls. The man yelled at him to ‘confess’ the things he had done in the past to his family in a tone that suggested that it was a conversation they had had before.

Her brother told them he had a gun hidden in his room back home in Minna, north-central Nigeria.

“My mom nearly had a heart attack,” she recalls. “A gun? Why was he talking about a gun? Why does he have a gun? We had taken him there just because of the drug addiction; why was he talking about a gun?”

Throughout the four-hour drive back to Minna, these questions ran through the minds of everyone in the car. As soon as they arrived home, they ransacked his room, searching for the gun. There was no gun.

Much later, when he was finally released to return home, he would admit to the family that he did not actually have a gun. He had merely said that because he hoped it would reduce the beating and humiliation he was subjected to. He needed to confess to something outrageous, to give the impression that he had been gotten at.

The thing that Shafa found most exasperating was that even in the middle of all that policing, her brother admitted to her that he and some of the boys there still found a way to procure drugs, sometimes through corrupt administrators and other times when they were sent on errands into town by the staff.

Dauda, the controller, however, insisted that inmates couldn’t get access to drugs.

“The moment they enter these premises,” he said, “they do not have any kind of access to drugs.”

But Muhammad confirms they could still get hold of banned substances in the institution, especially when they became senior boys. “The only thing is you won’t get as much as you were getting when you were home. Because sometimes when you are a senior boy, the staff will send you on errands inside the town, and you will have a chance of getting drugs there.”

Asked if he came out better than he went, Muhammad says, “Of course; definitely.” He has since gone on to graduate from university with a first class.

Braima, however, came back worse than he went in.

“He doesn’t even stay home anymore,” his sister says.

*This story was produced with support from Tiger Eye Foundation and the MacArthur Foundation.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter