Poor Infrastructure, Underfunding Frustrate Kano’s Basic Healthcare Programme

The Basic Healthcare Provision Fund (BHCPF) was touted as the saviour of ailing primary healthcare centres. However, the grand vision collided with a harsh reality, leaving the ambitious project gasping for breath.

Ladidi Ado’s* journey into motherhood took shape amidst the challenges of a semi-functional primary healthcare centre in her village. This chapter of her life began as she ventured into bringing her third child into the world.

Like her previous two births, which unfolded in the familiarity of her home, guided by the hands of makeshift midwives (ungozoma), Ladidi’s hesitation towards hospital visits wasn’t born out of reluctance but rather out of despair over the health disparities that make it difficult for people like her to access good and affordable health care services in rural areas.

She lives in Agalawa, a village in the Madobi area of Kano, Northwest Nigeria. The primary healthcare facility in her community, Agalawa Health Post, was intended to bridge the gap in healthcare disparities suffered by people in rural areas. But it has manifested various signs of neglect to the level that even those it intended to serve are leaving it for an alternative.

With broken ceilings sagging under the weight of time and shattered windows, the building wore the scars of abandonment. Furthermore, only two people work in the facility, which is meant to look after hundreds of women and their children.

“This is the problem,” Ladidi said. “If you rely on the health post, you may miss it all. So, women in this village find alternatives. They look for a local midwife and use traditional means to deliver their babies.”

Locals have said that the staff work mostly two days a week and close in the afternoon before the official hours assigned to them. When HumAngle visited the health post around 2 p.m., the facility was already closed and the only employee who worked that day had left. Residents explained that the workers came from distant locations.

Ladidi’s last pregnancy had unforeseen complications. Two weeks past her expected delivery time, she found herself waking up each day to the endless nightmares of troubled times.

“It was a new chapter for me, unlike my previous pregnancies,” she recalled.

The local midwife acknowledged the gravity of Ladidi’s situation, admitting that her expertise was no match for the challenges at hand. The only viable option left was seeking aid at the same health post they abhorred.

Ladidi had to be transported via her husband’s rickety motorcycle. Approaching the health post, her contractions surged. The motorcycle accelerated through uneven roads, but to their greatest disappointment, the facility was already closed.

“By the time we reached there, I had already forgotten what was going on. I was semi-conscious,” she said.

Ladidi’s husband decided that he had to take her from Agalawa to Kafin Agur, a distant community with a bigger healthcare facility. But before they reached their destination, Ladidi gave birth on the road.

“It was an unforgettable memory. I still feel like we should have stayed at home instead of giving birth on the road or, to be more precise, in the hut by the road,” she said.

Burji Health Centre: Neglected, in ruins

The experience of Ladidi and her husband was similar to that of Jummai Abdullahi and her daughter Amina.

When Amina entered the final stage of her labour, a sense of urgency gripped them. The nearest hope for medical attention lay many kilometres away from their house at the Burji Health Centre, a once-vital healthcare institution now plagued by dilapidation and neglect.

As they embarked on the journey to the hospital, the struggles of the primary healthcare centre mirrored the larger crisis facing not only Madobi but Kano State in general.

Dilapidated infrastructure, understaffing, a lack of essential medical equipment, and budget constraints have crippled this vital community health facility, leaving residents without access to crucial medical services.

Upon reaching Burji, Jummai and Amina found a closed hospital, deserted in the dark hours of the night. They returned home with a heavy heart.

Amina gave birth in the poorly lit confines of their home with amateur midwives, including her mother and neighbours. In the aftermath, Jummai reflected on the terrifying experiences of many women in her village.

It wasn’t only about operational hours due to the lack of staff; it was also about how the rooms have become dilapidated with no beds and other necessary medical equipment that could be used to attend to patients.

Patients who seek medical attention in this facility are often subjected to substandard conditions, including leaky roofs and inadequate sanitation facilities, posing serious health risks.

Rain has damaged more than half of the roofing in the patient room at Burji Health Centre. The ceiling, long bereft of any maintenance, sagged in resignation, weighed down by the heavy burden of neglect and raindrops. Sunlight streamed through the countless gaps, casting erratic patterns of light and shadow on the abandoned hospital beds with no sofas.

Free, but abandoned

In May 2023, the Kano State Assembly passed the long-awaited Free Maternal and Child Healthcare (FMNCH) Bill into law. This made the state the first in Nigeria to enact the law, a move that received wide commendation. The law is supposed to access to quality health services for women and children.

There are a total of 1,183 health facilities across Kano’s 44 local government areas (LGAs). Of this number, 1,142 are primary healthcare centres, amounting to 97 per cent of the total. Most of them are struggling to provide basic healthcare to people, especially in rural areas.

Madobi LGA has 20 primary healthcare centres, but most of them struggle to provide the basic services required of them. None of the 10 buildings visited during the course of this investigation met the minimum requirements. None of them had a good and functional patient room, and most of them had no water source or hygienic toilets.

The National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) specifies that all functional PHCs should be built on 4,200 square meters. They should have at least 13 rooms with good roofing, netted windows, functional toilets, clean water supply from a motorised borehole, and a disposal site. They should contain staff accommodation and be painted a green colour.

However, none of the PHCs visited has all of the above. In Birji, for example, the roofing has been damaged by rain and there is no water source. The staff in the facility lament that the distance and lack of accommodation are affecting their productivity.

According to the website of the Federal Ministry of Health, Burji Health Centre offers antenatal and eight other medical services for in and out-patients. But the reality, according to an employee who requested anonymity, is that none of the services mentioned get fully done. “It’s just on paper.”

“In ANC (antenatal care), for example, there’s only one person working, and sometimes the number of patients is so large that she can’t respond to them all,” he explained. Even if the few staff they have are determined to put in their best, he added, they can’t handle the services promised.

The hospital gets an average of 20 patients a day, most of them receiving antenatal care, while a few come for immunisation. However, it lacks the facilities to receive patients in very critical conditions.

Only seven staffers bear the weight of their roles with a sense of resignation. All of them commuted to work from distant places.

The problem is not limited to Madobi. In 2020, Connected Development (CODE), a non-governmental organisation, conducted an assessment of 49 health centres across Kano’s 44 LGAs and found that “all the PHCs assessed seem to lack some component of the basic requirements as outlined by the NPHCDA minimum standards for PHCs.”

While the website of the Kano State Primary Healthcare Management Board lists Burji and Kafin Agur Health Centres as operational for 12 hours a day, this investigation has found that the claim is false.

At Kafin Agur, this reporter found that the health centre was closed before 2 p.m., and at Birji, the staff confirmed that they operate for less than eight hours a day.

BHCPF intervention not enough

In 2019, an attempt by the federal government to save the ailing primary healthcare centres in Nigeria was introduced through the Basic Healthcare Provision Fund (BHCPF).

The BHCPF is a health intervention scheme established under the National Health Act (2014) to provide basic healthcare services to the poor and vulnerable. The intervention was touted as the saviour of ailing primary healthcare centres. However, the grand vision collided with a harsh reality, leaving the ambitious project gasping for breath.

With ₦948 million earmarked at the start of the project, Kano was at the top of the list of beneficiaries. It had 381 PHCs receiving funds under the programme and later expanded to 484 PHCs.

Research has shown that despite getting the lion’s share, the project has been faced with lots of challenges in the four years since its implementation started in the state. Challenges include insufficiently skilled health professionals, a lack of data management capacity, low community participation and awareness, poor infrastructure, and a weak financial management and accountability system.

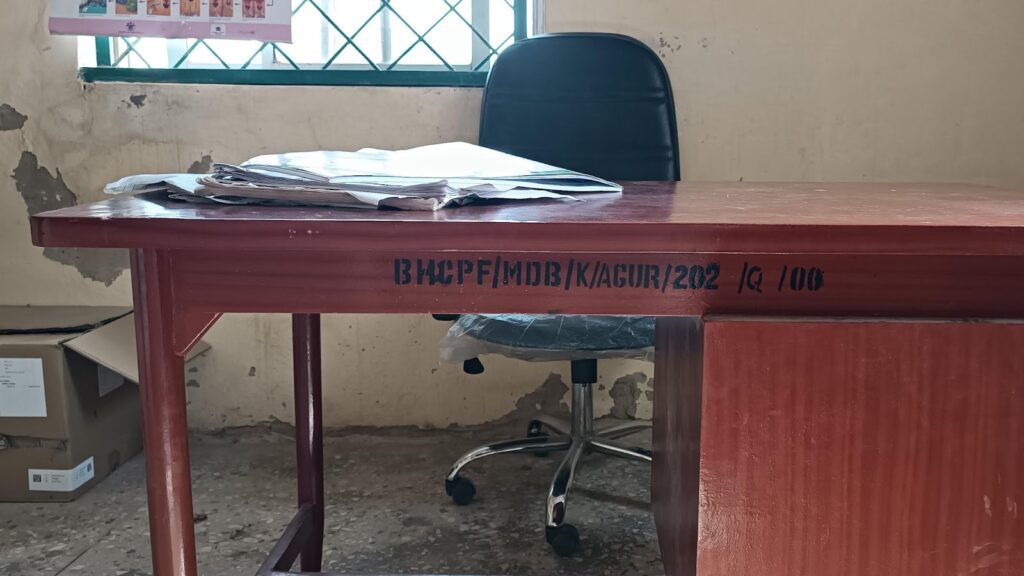

In Madobi, one PHC was selected from each of its 10 wards. They are PHCs in Kafin Agur, Daburau, Burji, Maraya, Dan Murna, Gora, Yakum, Chinkoso, Rikadawa, and Cikawa.

We found that all the health facilities face one or more of the challenges mentioned above, which frustrates the successful implementation of the BHCPF.

In Kafin Agur, the project supports three major components. They receive a meagre amount of ₦300,000 per quarter, expected to be shared across 10 priority areas. The areas include administrative system and infrastructure, financial system, human resources management, maternal and child health services, patient care management, essential drugs, laboratory, health management information system, utilisation and clinical outcomes, and community involvement.

“First of all, this health centre has only six staff members, including two casual workers,” an employee at the healthcare centre said.

“The first thing we do with the funds is pay the allowances of the two casual staff working on the project,” he explained. “We are also expected to renovate some rooms and buy drugs for the hundreds of beneficiaries under the project.”

According to him, the meagre amount given to the hospital can’t cater to its needs, especially as prices have increased. Most of the time, the drugs are exhausted before the end of the quarter.

“Inflation has affected everything, including the drugs that are being given to the BHCPF beneficiaries in this ward. What used to be ₦100 has now tripled or even quadrupled its price,” he lamented.

There are 343 beneficiaries from Akilu Memorial Health Centre and over 270 from Kafin Agur PHC.

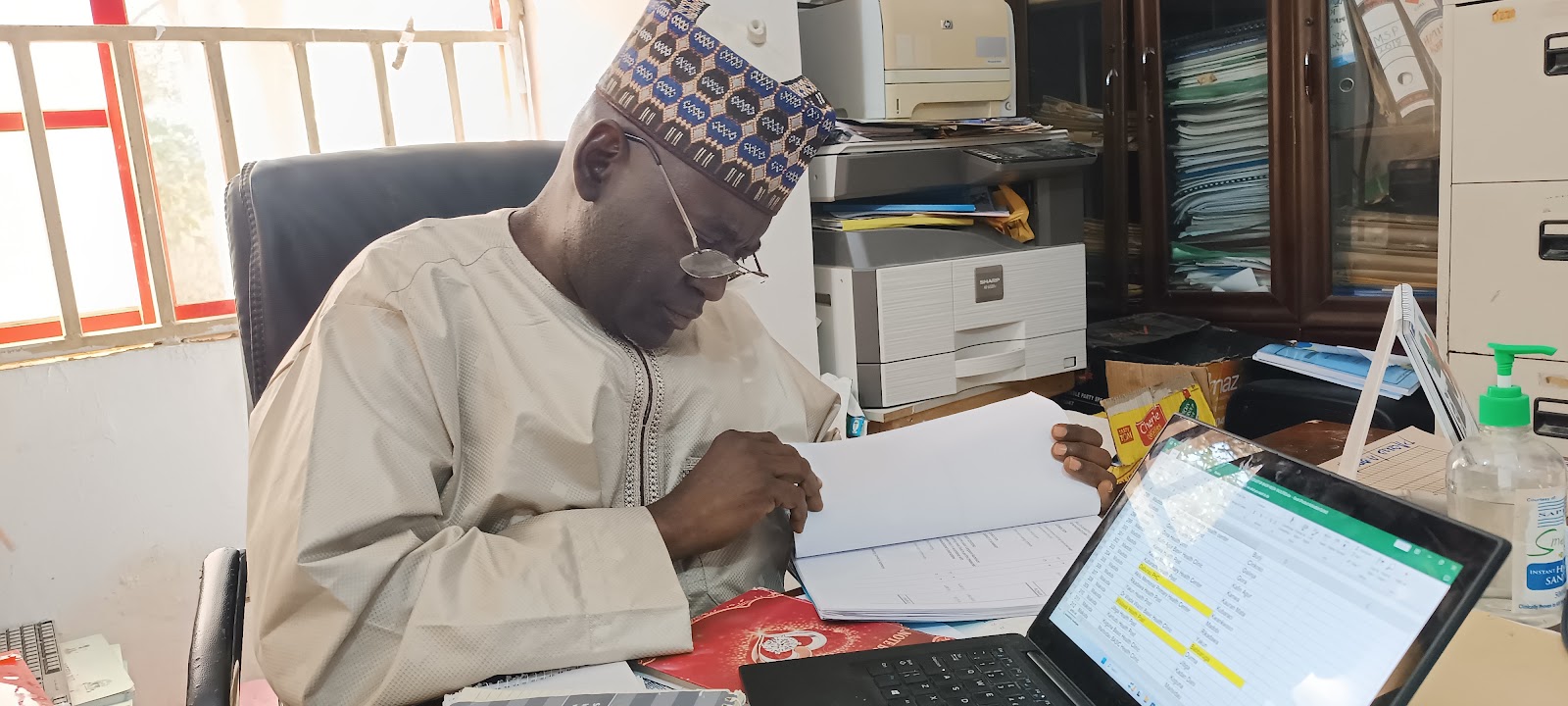

Mallam Bashir Sunusi, the Director of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation at the Kano State Primary Healthcare Management Board (KSPHMB), admitted that most of the PHCs in the state are struggling to survive even under the BHCPF.

“Let’s be realistic,” he said. “The BHCPF hasn’t come to alleviate all the problems that the PHCs are facing.” He explained that the money is insufficient, but it serves as a catalyst to help the PHCs work.

“Every month, the PHCs are expected to spend ₦100,000 across 10 priority areas and that’s ₦10,000 for each in this inflation,” he said. But, according to him, there’s a form of flexibility in spending the money. The PHC can take the money where it’s less critical and put it where the PHC needs critical attention.

The intervention, despite the meager amount, has helped in repairing damaged ceilings and renovating the patient’s room. “We also buy the medicine, although in a small quantity, to give to the beneficiaries,” the director said.

The selection of beneficiaries who receive the drugs is one of the programme’s most controversial aspects.

Some residents have accused local politicians and traditional rulers of hijacking the project for themselves. Habibu Lawal claims some of the people put on the list of beneficiaries at Akilu Primary Health Centre in Madobi don’t deserve it.

“The project’s aim was to target the weak and vulnerable, but it has been hijacked,” he said. “People who are in obvious poverty are not benefiting, while people who have known some people are at the top of the list.”

Some of the people selected have not been seeking care at the facility. “That’s the irony,” said one of the workers. “While some are lamenting that their names haven’t been on the beneficiary list, others are not coming to benefit despite having their names on the list.”

HumAngle reached out to the authorities at the local government level for comments on our findings and the allegations, but they replied that they were not authorised to speak without permission from the Kano.

Recently, the BHCPF management in the state conducted a reassessment of the beneficiaries and found some of them missing. “We are waiting for replacements,” the Kafin Agur PHC employee said.

On the dilapidated state of the PHCs, Sunusi said the state government is aware of their conditions and has kickstarted processes to get them working again. “There’s a plan to take one PHC from each ward across the 44 LGAs and renovate it to a standard, and the plan has already been approved by the state government.”

Sunusi said the BHCPF project is not entirely in the state’s hands because the money comes directly from the CBN through the Direct Facility Financing (DFF) programme.

“We have minimum control over it. Ours is to monitor and evaluate, and I’m telling you that the money being sent isn’t sufficient even though BHCPF hasn’t come to solve all the problems but to catalyse the solutions.”

*Not a real name

This investigation was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR).

Summary not available.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter