Older IDPs Neglected, Need Improvement – Report

Amnesty International (AI) has raised the alarm over the poor treatment of older displaced persons in Northeast Nigeria.

The organisation, in its latest report, stated that this set of displaced persons is largely overlooked by the Nigerian authorities and humanitarian responses.

The report – tagged ‘My Heart Is In Pain’ – focuses on older people’s experience of conflict, displacement, and detention in Northeast Nigeria

AI noted that their invisibility and neglect underlie the ways their rights are not respected.

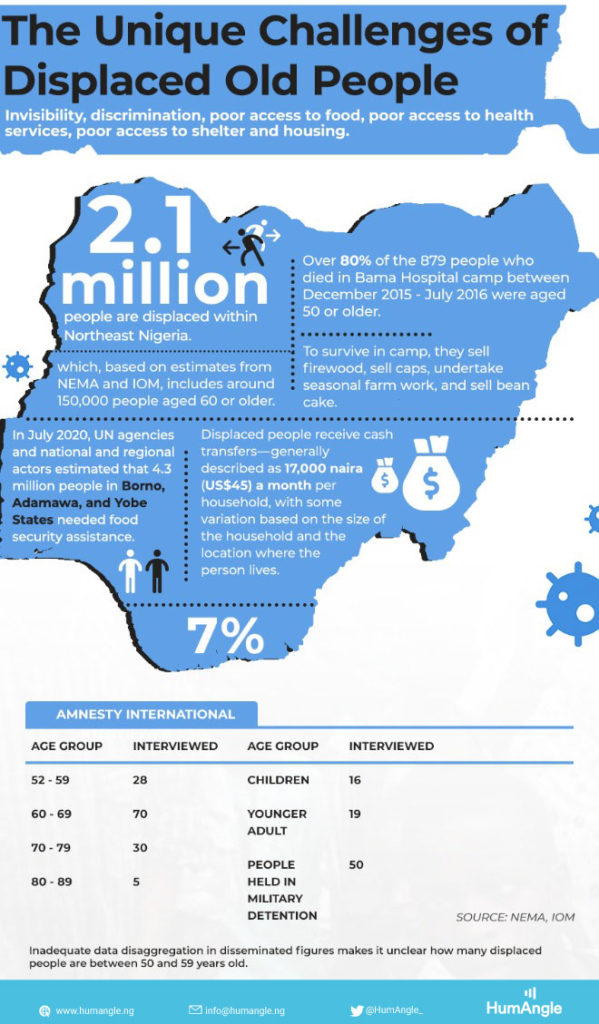

More than 2.1 million people are displaced within Northeast Nigeria, which, based on estimates, includes around 150,000 people age 60 or older; many women and men between 50 and 59 years old see themselves as older people and should be seen as such by the authorities.

“The federal and state governments are failing to meet these displaced older people’s needs and to protect their rights, including their rights to food, health, shelter, dignity, and non-discrimination,” Amnesty International said.

“Older people repeatedly described feeling unvalued and ignored; during assessments and in the design of humanitarian programmes, they are seldom consulted, much less meaningfully involved. Older women are especially excluded.”

According to the report, most displaced older people interviewed by Amnesty International said that food was their biggest concern.

They consistently described inadequate access to food and, in camps where the Nigerian authorities managed food assistance, almost all said distributions were repeatedly delayed, typically by weeks.

Displaced older people have limited access to livelihoods, the report said, even compared to other parts of the displaced population, making them heavily dependent on assistance.

Many described eating one meal a day and having to beg to survive.

In addition, displaced older people overwhelmingly do not have access to essential health services, despite often having specific health needs.

The report noted that while some camps have a clinic, displaced people said the clinics deal mainly with malaria, acute diarrhoea, and other emergency care.

Older people said medication for common chronic illnesses that disproportionately affect them, like hypertension and diabetes, is not available in camp clinics.

Instead, for such care, displaced older people must pay at every step: for the transport to a doctor or hospital; for the tests and care during a visit; for their hospital stay; for the transport to a pharmacy; and for medication.

Such costs are often impossible to bear. Many older people said they were forced to go without essential medication; others sold part of their food assistance to pay for medication.

The violence in Northeast Nigeria is in its second decade, with a resurgence of Boko Haram attacks and military operations in 2020, especially in Borno State.

The armed conflict has devastated individuals and communities across the region, with Boko Haram and the Nigerian military both responsible for war crimes and likely crimes against humanity.

Older people’s experience of the conflict has been largely ignored in media, human rights, and humanitarian reporting, AI noted.

Yet they face distinct and often exacerbated risks from both sides of the conflict, linked also to the intersection of older age, gender, and disability.

AI’s report examines crimes under international law that Boko Haram and the Nigerian military have committed against older people or that have affected older people in particular ways.

It also looks at the humanitarian response to the crisis in Northeast Nigeria, and how this response has neglected older women and men. The atrocities and wider neglect remain ongoing, especially across Borno State.

Poor Healthcare

Many older people across Northeast Nigeria have been displaced for half a decade. Camp health services respond primarily to emergency care, like malaria and acute diarrhoea, and support pre-and post-natal care.

Camp clinics, where they exist, are not equipped to treat chronic conditions that disproportionately affect older people, like hypertension and diabetes; this is a recurrent problem in humanitarian response.

Displaced older people in Northeast Nigeria are often unable to pay for such medication themselves, or at least to do so according to their needs, leaving many in a situation that violates their rights to health.

A decade of crisis marked by widespread atrocities has had a devastating impact on older people’s physical and mental health.

“Because of Boko Haram, we live in constant fear,” said a 57-year-old woman from Michika Local Government Area, Adamawa State.

“Many older people are now living with high blood pressure and so many have lost their livelihoods and loved ones.”

She said her husband, who was in his 60s, had died a year earlier due to hypertension and other illness she attributed to the conflict.

Depending on the camp, displaced people rely on on-site, off-site, or mobile clinics. But, at least in the 17 camps across Borno State from which Amnesty International interviewed people, care was not available for conditions suffered disproportionately by older persons.

Payment is required at every step of accessing such health care: for transport to a doctor or hospital; for tests and care during a visit; for a hospital stay, including food; for transport to a pharmacy; and for medicine. For many, such costs are impossible.

In three different camps, older people with severe cataracts said someone had written down their name, saying doctors would come to perform eye surgery. Months later, they had heard nothing more. AI shared more instances in the detailed report.

Damaged Shelters

In their villages, older people in Northeast Nigeria play a central role in providing for themselves and their families, as farmers, traders, and in raising livestock.

Most have done so for decades, often in the same village. That tie to their home and land is one of the main reasons why older people tend to be among the last to flee, despite threats from Boko Haram and the Nigerian military.

Leaving their village has a severe economic and psychosocial impact, as they go from being independent and valued to being dependent and invisible.

Many displaced older people live in damaged or otherwise inadequate shelters that provide little protection from rain and flooding. Some of the worst shelter conditions are in camps managed by the Nigerian authorities.

Older women at these camps told Amnesty International that when they arrived, they were only told where they could construct their shelters; no material or other assistance was provided.

They also reported that when they sought help from camp authorities to reconstruct damaged shelters, no assistance was provided.

Older people who headed households, and particularly older women, also felt excluded in distributions of essential non-food items, like blankets during the cold season.

Inadequate food

A woman around 70 years old in Farm Centre Camp, who was a primary caregiver for three grandchildren under the age of 10, described her ordeal: “We are hungry.

“The food provided is very small, and it doesn’t come on time… After the food is finished, I have to go and beg at Custom Market…

“I was a guinea corn farmer [in my village]. I had my own cows, my own farm. Now we are beggars. I’m suffering. My grandsons are suffering,” she added.

For many displaced older people in camps, the problems are even worse – they do not receive any food assistance because they have never been registered or find themselves inexplicably removed from registration lists; camp authorities have routinely failed to resolve the problems in a timely manner.

Amnesty International said it interviewed 15 older people in Borno State camps who had gone at least four months without food assistance, despite their repeated efforts to resolve the problems.

Such issues, the report said, arise for more than just older people, but older people appear disproportionately affected and can face more barriers in getting a resolution.

The report revealed that humanitarian assistance is limited, even compared to major crises in other countries.

“The cash or in-kind food assistance is insufficient to meet most displaced people’s needs; the health services are limited in what they treat, with almost no care for risks linked to older age; distributions of essential non-food items are infrequent, and when they occur, rarely reach everyone in a camp and seem to marginalize older people; and the delivery of material to construct or repair shelters is inadequate,” AI explained.

Odd Jobs For More Income

The report indicates that operating environment, with threats and restrictions from the conflict’s parties, as well as donors’ extreme underfunding of aspects of the humanitarian response, contributes to the challenges.

As a result, it noted that displaced people in Northeast Nigeria often find themselves in desperate need to supplement the assistance with income.

They undertake seasonal farm work in surrounding areas, getting paid with money or crops.

They collect firewood from outside camps, to sell and to use. And they sew traditional Bama caps or cook bean cakes to sell at market.

Livelihood options are limited for displaced people of all ages, but the displaced older people interviewed for this report described particular hardships.

Many said they were unable, for example, to walk several kilometres each day to get to farming areas or to collect firewood.

A 65- year-old man displaced to Water Board camp in Monguno, who had been a farmer and fisher in Baga, described: “The situation in the camp is too harsh.

“I can’t go get firewood. You have to hire a trolley for 500 naira and then go very far. Before I’d reach [the firewood area], it would be 2 p.m. I couldn’t even come back the same day.”

In areas where Boko Haram is active, displaced older people said the risk of being caught in an attack and unable to flee quickly further impeded their livelihood options.

Older people with disabilities or reduced mobility have even greater challenges.

“Two years back, I sold kola nuts,” said a 65-year-old man displaced to Dalori 2 Camp.

“I’d go and buy kola nuts and sell them. But now I can’t walk around so much anymore,” he said.

A few older women said they sold goods at markets outside their camps, but their income generation was in the clear minority among the displaced older people interviewed; even for them, the earnings were meagre, for example from selling a few vegetables or spices they planted in or near the camp, or from selling part of their food assistance.

And no displaced older person interviewed by Amnesty International had been hired by or knew an older person who worked for a local or international organisation operating in the camps.

The lack of access to livelihoods leaves many displaced older people with no choice but to try to survive on the inadequate humanitarian assistance provided or, for those with adult children in the same camp, to depend on what little their families can spare.

In addition to the lack of livelihood options, older people described significant challenges in accessing assistance equally.

The first problem, voiced by almost every older person interviewed, is that no one speaks with them about their needs and risks.

A 70-year-old man displaced to Stadium Camp said, “In the camp, no one has come and asked, ‘Where are the older men and women?’ No one has considered us.”

A man in his late 60s, displaced to Gubio Camp, said similarly, in speaking about staff from local and international humanitarian organizations: “Nobody has come to take care of older people.

“When people come, they don’t come to us, they go to the camp chairman and speak with him.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter