#NyiragongoEruption: Pompeii Is Alive! This Time, It Is In Africa’s DR Congo

Mt Nyiragongo in North Kivu, East DR Congo, is at risk of burying the surrounding areas in lava. In a situation akin to Pompeii’s burial by Mt Vesuvius, will Nyiragongo’s communities be saved?

Pompeii, the ancient (Roman) Italian city, was a hub of trading activities. Blessed with good soil, Pompeii farmed and feasted; close to the ocean, the city fished and dined. A trading route for the Roman empire, businesses flourished in Pompeii like Lions in a jungle of Antelopes. But Pompeii soon descended into the darkness that would cover the city’s beauty for centuries.

“Early one afternoon in the year AD 79, an enormous cloud began to rise from Mount Vesuvius in the Bay of Naples. The cloud was initially white, but steadily turning grey, and shaped like an umbrella pine tree, causing one onlooker, the 17-year-old Pliny the Younger, to observe: ‘It was raised high on a kind of very tall trunk and spread out into branches,’” historian, Daisy Dune, wrote of Pompeii’s end.

“The teenager was staying with his mother and uncle in the port town of Misenum, around 19 miles from Mt Vesuvius. Situated on the opposite side of the bay from the city of Pompeii . Misenum was home to one of Rome’s fleets. From there, Pliny the Younger and his uncle, Pliny the Elder, the fleet’s commander,” saw Pompeii being swallowed by a rain of lava falling from Mt Vesuvius; a tragedy many have described in different words. But Pompeii’s death was foretold, it just wasn’t prepared for.

Pompeii’s historical archive on the World History website mentions an early warning through multiple earthquakes around Mt Vesuvius in 62 CE. The quakes were so powerful that they destroyed several buildings and killed thousands. “However, slowly, the town made repairs, some hasty and others more considered and life began to return to normal.”

In 79 AD, “ strange things began to occur. Fish floated dead in the Sarno, springs and wells inexplicably dried up and vines on the slopes of Mt Vesuvius mysteriously wilted and died. Seismic activity, although not strong, increased dramatically in frequency. Although some people left the town, the majority of the population seemed to still not be too worried about the events that were unfolding but little did they know that they were about to face an apocalypse.”

Around the time of Pompeii’s Lava bath, there were between 10,000 and 20,000 inhabitants in the city. “Just after midday on August 24 (AD 79), fragments of ash, pumice, and other volcanic debris began pouring down on Pompeii, quickly covering the city to a depth of more than 9 feet (3 meters) and causing the roofs of many houses to fall in. Surges of pyroclastic material and heated gas, known as nuées ardentes , reached the city walls on the morning of August 25 and soon asphyxiated those residents who had not been killed by falling debris.Additional pyroclastic flows and rains of ash followed, adding at least another 9 feet of debris and preserving in a pall of ash the bodies of the inhabitants who perished while taking shelter in their houses or trying to escape toward the coast or by the roads leading to Stabiae or Nuceria. Thus Pompeii remained buried under a layer of pumice stones and ash 19 to 23 feet (6 to 7 meters) deep.”

In a manner similar to Pompeii’s burial by Mt Vesuvius, Goma and other towns surrounding Mt Nyiragongo in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo-Kinshasha) are witnessing a slow descent into a fiery bath. Like Pompeii, Goma wants life to return to normal. But the mountain is singing, and it is a song of tragedy.

History of the Nyiragongo eruption

On May 22, 2021, local news in DR Congo — and eventually the rest of the world — was filled with stories of a volcano eruption around Goma, North Kivu, in the country’s eastern region. The eruption was from Mt Nyiragongo, and the casualties are still being counted.

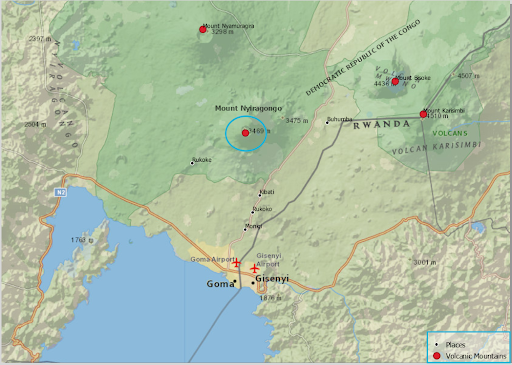

Mt Nyiragongo is an active volcano in the Virunga Mountains of East Africa . It is in the volcano region of Virunga National Park , Congo , near the border with Rwanda , 19 km north of Goma. Nyiragongo rises 3,470 meters high and has a main crater, 2 km wide and 250 meters deep, containing a liquid lava pool.

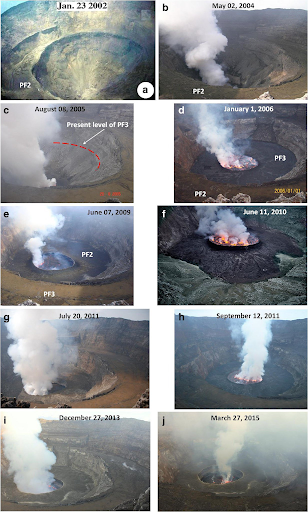

This is not the first eruption in Nyiragongo’s history. Since 1882, it has erupted at least 34 times, including many periods where activity was continuous for years at a time, often in the form of a churning lava lake in the crater. The existence of the lava lake had been suspected for some time but was not scientifically confirmed until 1948. In 1977, some 2,000 people were killed , and in 2002 Goma was largely destroyed by lava, leaving more than 100,000 people homeless and creating a refugee crisis . This year, lava stopped short of Goma’s city limits, but the eruption killed more than 30 people and destroyed several villages.

2/2. En 1994 il est réapparu et resté actif jusqu’en 1995, où il s’était encore solidifié jusqu’à l’éruption de 2002. Le lac de lave qui s’est vidé le 22 mai 2021 est apparu en mai 2002, resté actif sans interruption

— Charles Balagizi (@CharlesBalagizi) August 27, 2021

The impact of these eruptions over the years has been nothing short of devastating. Yet, after each bout — often followed by displacements and a refugee crisis — like the people of Pompeii, life returns to ‘normal’ in Goma.

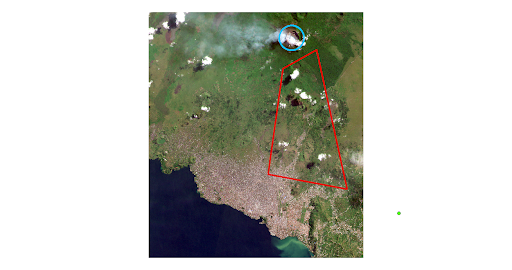

When the last major eruption was recorded in 2002, the population around Nyiragongo was estimated at 210,000. As of May 2021, this population is now around 670,000. The people are not the only growth in the areas surrounding the breathing volcano. Development according to satellite image analysis of the land cover of the areas around the volcano, including the nearby Goma town, revealed that before 2002 only 46.4km of built-up surface (places with buildings) was around Nyiragongo. After the 2002 eruption and subsequent return of people, the built-up area was at 38.5km. By 2016, however, it had grown to 71.3km of built-up area . When the 2021 storm fell, it grew to 105.7km and went down to77.7km after the eruption.

That people return to the surroundings of the mountain, despite the risk, makes it necessary to examine the geographical and economic merits of the areas.

What makes Nyiragongo so appealing?

GIS data reviewed by HumAngle’s GIS expert, Mansir Muhammed, revealed that Nyiragongo is surrounded by a natural vegetation landscape. In the places closest to the mountain, the human activities are so low, they are considered wilderness area. However, the environment around the mountain is consistent with shrublands across all sides leading away from the vent of the volcano. The plants are short and colorful with flowers growing alongside human cultivations from agricultural activities.

The plant type is also an indication of nutrient-rich soil which is mostly because of the minerals present in volcanic ash. This is why the Nyiragongo area is an agricultural environment.

Additionally, the vegetation cover over this region is densely distributed with the assemblage of shrublands. It is packed with thick forest type vegetation that provides a convenient ecosystem from which wildlife could exist. The density and extent of this forest are sufficient to service the communities neighboring the volcano.

These assessments cover the geography of the area for up to an 18km radius that includes communities such as Goma, Buhumba, Rutoke, Kibati, Monigi, Colline Bugu, Kanzene, and Ngiko CD.

Nyiragongo is a mountainous region (3330m above sea level) with communities situated around it at lower elevations ranging from 1700m to 1900m above sea level. These are considered to be highland communities even though they are at the base of the mountains’ elevation profile.

Communities such as Goma, Buhumba, Rutoke, Monigi, and Colline Bugu are situated downslope of the volcano. This puts them at the most risk of lava flow from the eruption by sheer mechanical pressure flow of the magma based on gravity. Their average elevation is about 1500m above sea levels.

The major town near Nyiragongo is Goma (75.72km area), which is between 13 to 17km from the volcano. However, the pockets of communities around the area have an average coverage of between 5 to 10km area. Buhumba and Rukoko are 8km away from the volcano. Monigi is 10km away, while Kibati is situated at the foot of the mountain range and is just 7km away from the vent of the volcano.

One of the discoveries from the GIS analysis is that, unsurprisingly, agriculture is a prevailing economic activity in the region. This is apparent due to the distribution of farmlands across the landscape of the Nyiragongo. The residents either build residences within their farms or cultivate fields near their residences.

Due to the proximity of Goma town to Lake Kivu, fishing is commonplace among residents. The lake houses some indigenous fish species which are of great importance economically and nutritionally for the local population.

Goma and its surroundings are economically and agriculturally reminiscent of Pompeii, and the recent eruption is a strong warning like the one received by Pompeii before the final rain of pain.

The ruins of Nyiragongo

The eastern region of DR Congo, where North Kivu is situated, and conversely Nyiragongo, has been under attack for years now by the Allied Democratic Force (ADF) , a terror group that originated from neighbouring Uganda.

The ADF was created in 1995 by former military officers loyal to the deposed Idi-Amin, and they went to war with Uganda’s then-new leader, Yoweri Museveni, over alleged persecution of Muslims. The Ugandan army defeated them in 2001, forcing a relocation to DR Congo, where it re-emerged in 2014.

President Felix Tshisekedi on May 6, 2021, declared a siege on Ituri and North Kivu regions, to curb or eliminate “recurrent rebel activities in the two provinces of the eastern DR Congo which have been the bedrock of atrocities against the civilian populations by various armed groups.” According to the UN’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, the ADF has killed about 200 civilians and displaced nearly 40,000 others in Beni since Jan. 2021. The rebel group also targets government and UN troops.

The state of siege, therefore, meant that the eruption met a population that was already exposed to terror attacks and struggling to adapt to heavy military presence monitoring daily lives. These farming and fishing communities were also suffering from diminishing resources because of the siege’s impact.

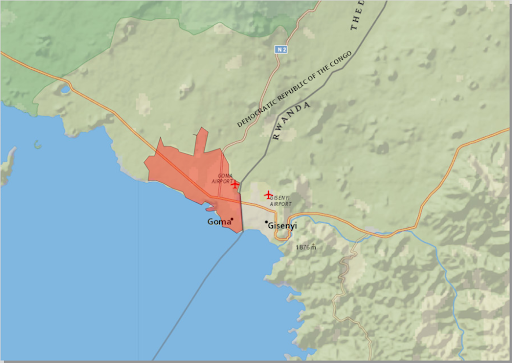

As of June, when counting was still at its early stages, Modeste Mutinga Mutushayi, DR Congo’s Minister of Social Affairs, Humanitarian Action and National Solidarity revealed that 31 persons lost their lives with seven dying during the evacuation, while 24 were burnt alive by the lava from the eruption. His report indicated that 247,352 persons from 41,225 households were displaced from Goma to other parts of DR Congo while others crossed the border to neighbouring Rwanda.

In a video, Geoffrey Kallebo Denye, an emergency communication specialist with World Vision, an international humanitarian organization, shortly before the carnage described the fear and uncertainty thus: “We feel anxious. Does this mean we are going to have another eruption?”

And almost like a response, another victim, although unnamed by the organisation, said, “We don’t know where to run to. Parents are afraid that their children don’t even have food. They don’t even have room to sleep.” At least 100 children, according to World Vision, were separated from their families, of which Denye added that “children were alone at home, everyone was running in different directions, panicking.”

Unlike in Pompeii, where attempts to escape were mostly done on feet, the Congolese situation saw carts and cars attempting to make the escape. Although faster, some of the deaths reported in the evacuation have been blamed on the cars. This means that there is almost no outrunning the eruption once it starts. Not when Nyiragongo is considered one of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world because of its particularly fast-moving lava that can flow at a speed of about 100km per hour.

Hundreds of thousands of people have been evacuating the city of Goma in #DRCongo, after a worsening series of tremors following the #NyiragongoEruption. We are there, supporting those who are displaced. pic.twitter.com/QPSRJiBFMv

— Andrew Morley (@andrewmorley0) May 28, 2021

In DR Congo’s eastern region, death is one eruption away; either from a gun or from a volcano.

Patrick de Marie C. Katoto, a lecturer at the Catholic University of Bukavu, who has done extensive research on Nyiragongo, shed light on the health hazards the local population will face or are currently facing.

He said, “Volcanic ash – composed of tiny particles of rocks, minerals, and volcanic glass – is a major health concern. When inhaled it can cause lung damage. For instance, one long-term effect of volcanic ash is silicosis a disease that can cause lung impairment and scarring. Inhaling volcanic ash can also cause suffocation, leading to death.”

The strong acids it contains can cause skin irritation and eye problems. It can, additionally, lead to neurological disorders if its toxic minerals are deposited in natural water sources or otherwise affect, plant, animal, and human life when the ash traps toxic gases in the air.

“Mount Nyiragongo is one of the most prolific sources of sulfur dioxide on earth. Since September 2002, this volcano has had a permanent lava lake which persistently releases a plume of gases rich in sulfur dioxide and carbon,” Katoto noted.

“Sulphur dioxide can irritate the skin and the tissues and mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and throat. It can also aggravate chronic conditions including asthma and cardiovascular diseases.”

The earthquakes and tremors caused by eruptions could also lead to building collapses. In the case of Mt Nyiragongo, another concern is that they could disturb the methane and carbon dioxide concentrations in the nearby Lake Kivu, thereby causing suffocation among locals.

Despite all of these, the communities are starting to rebuild. Satellite data surveyed by Mansir Muhammed indicated that weeks after lava flowed down the slopes of Mt Nyiragongo, reconstruction had already begun on damaged infrastructure. The SkySat image below shows National Road No. 2—which links Goma with the cities of Butembo and Beni to the north—where it crosses a fresh lava flow.

Humanitarian aid

DR Congo is not rebuilding alone.

Benoit-Pierre Laramee, the Canadian Ambassador to the country on Thursday, July 8, declared that “for this year (2021-2022), Canadian humanitarian aid (to DR Congo) would amount to 39 million Canadian dollars. This is an increase of 23.4 per cent as compared to last year’s assistance which stood at 32 million dollars.” The aid is expected to cushion “the needs of Congolese who are victims of conflicts in the country or natural disasters, displaced persons or refugees.”

At displaced people camps catering to victims of Nyiragongo, organizations like Hand on Heart , DP World , Doctors Without Border , and others have been providing the displaced with basic amenities, while the UNOCHA has asked for $25 million to provide aid.

But with the growing poverty in DR Congo, especially in the region facing a siege, the resources for Nyiragongo’s victims may not be enough. A displaced person who spoke to HumAngle complained that they were shocked to notice that new lists were being developed and old, authentic ones, rejected at the distribution sites. “There is partiality in the distribution of assistance. Those who are receiving goods and materials sent by the government are not the real displaced persons but (other) locals of Nyiragongo,” they added, indicating that limited resources are now causing people to pretend that they are displaced.

Even if the humanitarian aids were to be sufficient and things were to return to ‘normal,’ Mt Nyiragongo is not done with its surrounding ecosystem.

Nyiragongo, Pompeii; is this the end?

Nyiragongo’s singing volcano is being treated in some quarters as an encore but its performance has only just started. Although the volcano was being monitored by a team of scientists at the Goma Volcanic Observatory (GVO), with seismic data produced every four minutes and temperature data produced every ten minutes, continued funding for the GVO is in doubt, as the World Bank decided in 2020 to terminate its contributions .

François Kervyn, director of the natural hazards division at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Belgium, which installed a network of seismometers around the volcano, indicated in 2020 that GVO also faces other challenges.

According to him, “the network requires constant maintenance, because of vandalism, theft, and lightning damage. Several seismometers are currently out of action. But the civilian unrest in the area makes repairs dangerous.” In 2020, “13 park rangers were killed in an ambush in the surrounding Virunga National Volcano Park.” It is a trap.

One of the GVO’s duties is to set up plans for Goma’s evacuation and issue the alarm if an eruption occurs. Although the extent of its warnings in the recent eruption is relatively unknown, it is believed that there must have been some.

In Pompeii, residents must have overlooked the imminent eruption as a minor disturbance that would soon leave if it was ignored enough, and it seems a similar pattern is being recorded around Nyiragongo, especially if the speed at which rebuilding is being done around such a dangerous place is considered.

One of the most dangerous volcanoes in the world with a speed faster than what many legs can outrun, and almost at par, or even faster than many cars, the areas around Nyiragongo are at risk of being swallowed by lava someday in the future. Patrick Katoto said of the impending danger: “Unfortunately, there aren’t many people can do to protect themselves aside from moving away – especially children, elders and people with asthma. If possible, people must stay inside a well-insulated house (doors and windows closed) or wear a gas mask (rarely available) outdoors. This will be an additional health challenge given the current COVID-19 pandemic if not well addressed.”

Paulo Papale, Director of Research at the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, similarly appealed , “The communities in and around Goma must be protected from the volcano; the humanitarian disruption from millions of thousands of homeless people must be prevented; the political instabilities following massive and uncontrolled country border crossing must be avoided. The rifting process and the eruption of magma can’t be controlled. Under such conditions, one should either relocate the town, which would be extremely difficult for a town the size of Goma (which also has a strategic location and political relevance) or at least reduce the risk to controlled levels.”

In a country ravaged with multiple humanitarian crises, most of which are concentrated in the same region, the possibility of people totally leaving the Nyiragongo areas is next to none. It is only a matter of time before the next lava flooding happens. But, at what point will Mt Nyiragongo become Mt Vesuvius? When will people leave and not look back? Who will help them to quit Pompeii before it is too late?

All Satellite data, except where otherwise stated, were provided by Planet and extracted by Mansir Muhammed for HumAngle.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter