Nigeria’s Deradicalisation Programme For Terrorists Has No Place For Women

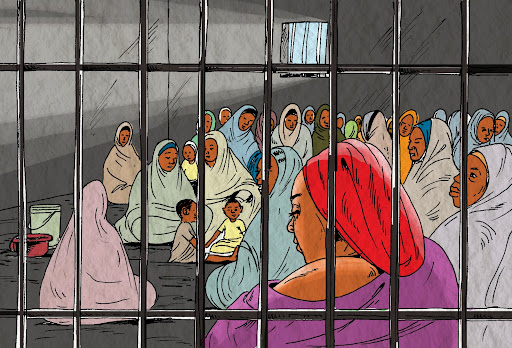

There are women within the Boko Haram insurgency who have recently deserted but Nigeria’s deradicalisation programme has no place for them.

She has a quiet demeanour about her. Nothing in her stature lets on the power she wields among the other women as their leader, the fact that she is a Boko Haram deserter, or that she had once been married to a commander in the terror group. Or even that she has spent nearly a decade in Sambisa forest among them.

“When you have spent nearly 10 years of your life living amongst Boko Haram, it is not possible not to become one of them and believe in their ideologies,” she is saying. Her voice is low, and her words, measured. From the gaps between her words and the way she struggles to choose them carefully, it is clear she still hasn’t decided whether she can trust this reporter.

Her name is Hafsah Ibrahim* and she was abducted by the Boko Haram terror group in Borno State, northeastern Nigeria, during the early years of the insurgency. She spent nearly a decade with them. Now she’s back home.

Slowly, as she talks, the suspicion dissolves.

“There is much difference between the previous and present Boko Haram members,” she finally says. “These ones are the total opposite. The true Boko Haram is what raged between 2014 and 2017. Those ones were truthful. Now? They have commercialised it. They are no longer doing it for the fear of God. It is no longer God’s work. These ones say they want peace. Some of them even say sins like adultery are not haram [forbidden].”

She begins to talk about suicide bombing in the early years of the insurgency and what it meant to prepare young girls for the act. She refers to it as istishhād, an Arabic term that translates to mean ‘a heroic death’ or ‘martyrdom’.

First, their hair is woven in a fine manner. And then they are given brand new clothes to wear. “So that they can enter Jannah [paradise] with brand new clothes and well dressed.”

This is under the premise that they will die as martyrs.

Some of them refuse to eat before going, she says. They say they do not want anything to do with earthly food, as they can already perceive the smell of food in heaven.

Ummi is one woman whose niece detonated a suicide bomb in a mosque in Borno. She had been so excited to do it that she tried to convince Ummi to do it too. Her family were deeply heartbroken by her decision.

“We asked her what the problem was. I asked her if she was simply tired of life. Her father even thought that maybe it was her stepmom that had treated her so badly that she opted to die rather than go on living with her – because her mom had died. But she said no. She really just wanted to do it because she had been brainwashed by the insurgents and she believed it to be the work of God.”

Does Nigeria deradicalise women?

Nigeria’s deradicalisation, rehabilitation, and reintegration programme, codenamed Operation Safe Corridor (OSC), is ideal to cater for people like Hafsah; victims of the insurgency who were abducted and forcefully indoctrinated and subsequently became radicalised.

However, the programme has come under heavy criticism. HumAngle spoke to graduates who said they were kept in unbearable conditions and often left without food. They also said that the process of their admission was not structured as there had been no screening to ascertain if they were truly deserters. They said they had never had anything to do with Boko Haram and yet were admitted into the programme against their will.

In 2017, during the first cohort in the current model being used, six people were admitted: three women and three men. Though hundreds of people are now being admitted yearly, no women have been admitted since.

HumAngle spoke to the three women in the first cohort about their experiences and found that they had all been abductees of the terror group who had escaped, and not necessarily Boko Haram surrenders or deserters.

They also reported being subjected to wearing bikinis in the open during the programme and shaking the hands of men despite it being against their religious beliefs, to prove that they were not radicals.

“They gave us panties and bras to wear and go out in the open. And you can’t refuse, because if you refuse they will say you still have Boko Haram in your head,” one of the women told us. HumAngle reported how declining to shake General Buratai’s hands for personal and religious reasons allegedly fetched the women an extra six months in the camp as the refusal was interpreted as them being extremists.

Dr Fatima Akilu, a behavioural psychologist who designed and implemented the first deradicalisation programme in Nigeria, told HumAngle that it was important to deradicalise women.

She shared that, in 2015, she deradicalised 63 women who had been rescued by the military from the terrorists and found that it was more difficult to disengage them from the ideologies than their male counterparts. There were also cases of some of the women finding their way back to the terror group after graduating from the programme.

The programme had psychologists, recreational activities, and imams who could help with ideological disengagement.

“We had an Imam that we engaged for the purpose of ideological disengagement. We had psychological and trauma counselling; we also had educational classes and helped them in developing critical thinking skills.”

Asked why the programme stopped admitting women, she explained that, technically, it did not stop. The programme simply ended when the current governor of Borno State came into power and decided that he did not want to continue with it.

“I think there is a misconception with the thinking in our society that women are fundamentally harmless and always victims. Women are not always victims, as we’ve seen. We’ve seen a lot of them as perpetrators. And so I think women should go through the same screening process as men. If they are found to have played active roles in the insurgency, they should be segregated and sent to the same kind or similar programmes as the men…”

She also explained that the active roles women play in the insurgency differ.

“They have been recruiters. In some cases, women have engaged in combat. They’ve held slaves. They’ve committed a lot of atrocities.”

Hafsah confirmed to HumAngle that women did engage in combat and in many cases had the task of drawing men who had fallen on the open field to cover their bodies.

“Sometimes women help nurse the ones who are wounded during battles. Other times, they help draw back the corpses.”

One major risk of having radicalised women back in the society unregulated, according to Dr Akilu, is that they may end up helping to silently recruit members for the terror group from the communities they live in, as women have been known to be active recruiters. They could also find their way back to the terror group as was seen with even those who were successfully deradicalised.

Hafsah said that some deserters from Boko Haram who surrender to the Nigerian state do so “because they hear things are better here. Then they come and realise that things are not the way they thought they were. So they go back.”

She struggles with a means of livelihood, she says. Many times, even food becomes difficult to come by for her and her baby.

“There are times when I miss my former life.”

Life as a Boko Haram commander’s wife

Hafsah’s early years in the group were blissful and enjoyable. She was married off to an Ameer in the terror group who she says treated her well.

“The Ameer was kind to me, he treated me nicely,” she remembers. She had three co-wives and they were all adequately provided for, she says. They were provided with clothing, food, and everything they needed and, sometimes, wanted.

“We lived a European life there. He gave us the kind of clothes he wanted us to wear. He gave us jean trousers, tops, shoes, and even crop tops. I don’t know where they got them from. He gave us sexy nighties too; the nighties are as soft as a cat’s fur.” Here, she laughs gleefully.

“He gave us mirrors to do our makeup and corrected us where we were wrong. When our hair got old, he helped us to loosen it. He cooked for us and even washed for us. He made us laugh. You can’t even get mad at him. This was all from my first husband. The one that was an Ameer.”

She talks about instances of her husband holding a mirror up for her as she tried to make herself up, and telling her when her kohl was drawn finely and where it needed to be adjusted. It is a memory that brings a childlike softness to her eyes.

Another topic she speaks passionately about is her midwife duties in the settlement.

“I knew nothing about midwifery before, but when I was there I somehow learned the skill.”

When her attention is called to a woman in labour, the first thing she does when she gets to the woman is to ask her to stand up. Then she observes the shape of the stomach to know where the head of the foetus is positioned; if it is positioned correctly. This determines how she will proceed.

“I ask the woman to stand up straight and I look at the stomach to see how the shape is. Oftentimes she’s not actually in labour, but she is close to. So it’s after a few days that she goes into labour. Even if it is in the middle of the night, they will wake me up […] Then I’ll hold her and tie her upper arm. Then we take walks until the labour is in full swing. I have never had any complications with helping people give birth.”

When her husband died, however, her status was relegated and life as she knew it ended. As soon as she was done with the mourning period, they married her off to someone else.

“You can’t stay without a husband in the forest. It is like they are counting the days. Once you reach certain months, they get you married. If not, they will say you want to run away; all eyes will now be on you.”

Her new husband turned out to be the complete opposite of her deceased husband. He was not on the same pedestal or social class, she says. He was a foot soldier. He was not only unkind to her, but he was also physically abusive. He often beat her up. Once, when she was pregnant, he beat her so badly that she did not feel her baby move in her stomach for two weeks, she says. She thought she had lost it. But one day she felt a kick. During the two weeks of anguish and uncertainty, she shared her concerns with him.

“When I told him the baby was not moving, he didn’t care about it. He even said that’s my problem, I should die if I want to,” she says. One can tell from the pain in her voice that she still has a lot of contempt for the man.

Despite her impeccable midwife skills, when it was time for her own childbirth with that pregnancy, she suffered complications, including uterine prolapse, a condition common among the women.

She suspects that her complications were a result of the physical abuse she was subjected to by her husband, especially the episode that led to her baby not moving for weeks. It was so deeply traumatising that she knew she had to leave the terror group.

Nine days after her delivery, she left with her baby. “I left because the disregard and maltreatment were too much from my second husband,” she says.

“Of course, I agreed with their ideologies,” she admits when asked. “In fact, the day I left, I was crying. I kept thinking: Am I really leaving this place?”

She talks about the pressure she’s been facing from the militants to return.

“In the early days, they kept calling me to go back. They said they never thought that I, of all people, would run away from the group.”

This report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter