Nigerian IDPs’ Struggle To Keep A Roof Over Their Heads

Displaced people in northeastern Nigeria find themselves in difficult situations as they face evictions by landlords and are forced to pay for accommodation in overcrowded camps.

Hajjara Habiba’s life has been a relentless cycle of displacement and hardship. Ten years ago, her world was upended when Boko Haram forced her family to flee their home in Baga and seek refuge in Maiduguri, Borno’s capital city in northeastern Nigeria. They settled in the Maiduguri stadium, enduring years of uncertainty and deprivation.

In 2020, the government resettled people from Baga, and Hajjara, along with her husband and his three other wives, relocated there.

However, life in their hometown was far from what they had hoped for. “Life was difficult, and hunger was everywhere in Baga. Our husband was doing nothing because there was nothing to do. Access to the farm was impossible,” Hajjara recalled.

Because of the food crises, two of her co-wives eventually left, seeking solace with relatives in other states. Hajjara, her husband, and his first wife struggled to survive, but as conditions worsened, she made the difficult decision to return to Maiduguri one year after they were resettled.

Left alone to fend for her six children, she found herself residing near the fence of Maiduguri International Airport, earning a living through menial jobs as a house help. However, it wasn’t enough to support her family.

She occasionally hears about life in Baga. She wishes she could travel to meet the rest of the family, but when she remembers the hardship there, she shrugs off the thought.

Eventually, security guards sent her packing from the airport premises, forcing her to find another place to stay. Alone and desperate, she settled in an unconstructed building far from the city centre, where life without food or business became increasingly difficult. Resorting to begging and doing odd jobs, she scraped together enough money to start a small business selling groundnut cakes.

But even then, survival was uncertain. Eventually, Hajjara found refuge in the Shuwari Five makeshift camp, where she rented two small rooms for herself and her children. She pays ₦5,000 ($3.5) for each one. She and her three girls squeeze together in one room while her three boys occupy the other.

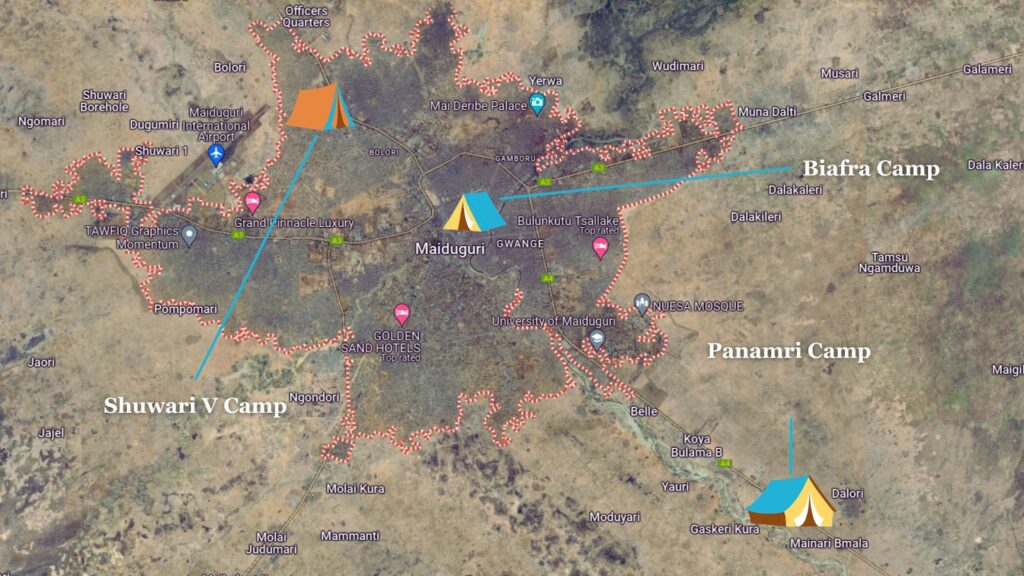

The Borno state government recently embarked on a massive resettlement programme that led to the closure of multiple displacement camps in and around Maiduguri. Between May 2021 and December 2022, the authorities closed nine camps and relocated over 153,000 displaced people. However, many of the inhabitants have stayed back in the capital city, mostly because of insecurity and the absence of livelihood opportunities in their ancestral communities.

The government’s approach raises questions about compliance with local and international instruments such as the National Policy on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and the African Union Convention for the Protection and Assistance of IDPs in Africa, which address such issues as forced displacement or resettlement and the protection of the interests of displaced people in such circumstances.

HumAngle recently went around makeshift displacement camps across host communities in Borno state and documented cases of repeated displacement of families already grappling with precarious living conditions and exploitation.

For residents of Biafra, Panamri, and Shuwari Five displaced communities, their journey is marked by a continuous struggle against bureaucratic hurdles and social barriers that prevent them from reclaiming their lives. They find themselves in difficult situations, facing evictions by landlords and being forced to pay for accommodation in overcrowded camps.

For Hajjara, the struggle for shelter is an ongoing battle against the odds.

There are 292 shelters in the section where Hajjara and her children live at the congested Shuwari Five camp. Each shelter measures 4 feet by 8 feet. This is smaller than the size of a queen-size bed, which measures 5 feet by 6.67 feet, providing limited space for the residents.

The situation is particularly depressing for vulnerable groups, such as women, who care for their families while navigating the challenges of displacement, including limited access to food, reproductive healthcare, and gender-based violence.

Neglected

In the vast expanse of renovated road that stretches from Maiduguri down to Bama through the heart of Konduga, amidst the ruins left by Boko Haram, lies the makeshift camp of the Panamri community.

Once a thriving agricultural community under Alau Ward in the Jere area, Panamri was uprooted eight years ago by a brutal attack that razed their homes and forced them to flee for their lives. Now, they reside in Alau Village, clinging to the hope of a return that seems increasingly distant with each passing day.

Home to over 150 households, the residents have endured years of hardship as they strive to rebuild their lives amidst the uncertainty of displacement. Their story is one of resilience but also neglect.

“Since we settled here, it is only Christian Aid that offered us humanitarian assistance and it only lasted for three years. We haven’t got any form of assistance since then and now it has been over eight years since our village was displaced,” said Modu Alau, a representative of the Panamri displaced community.

With no ongoing support, the residents have struggled to access basic necessities such as food, water, healthcare, and education. They have also lost the means to engage in farming as they used to before their displacement.

According to Modu, politicians visited them during the last general elections and distributed some food and non-food items as part of political campaigns. “What they shared with us could not satisfy any individual, but because they wanted our votes, they gave us the little stuff as compensation,” he said.

Struggle for shelter

The challenges facing Panamri extend beyond mere survival. As if the trauma of displacement wasn’t enough, the community has faced additional hardships from unexpected sources. One such challenge came from property owners now reclaiming their lands, leaving many displaced families without a place to call home.

“We are residing on lands that did not belong to us and the owners are eventually confiscating their lands. This has been happening regularly since we set up our camp,” Modu told HumAngle.

“The government was aware of our displacement, but it did not offer us land to stay in. We begged the host community of Alau village to allow us to reside on their lands. Some agreed, whereas others did not. Those that agreed are gradually collecting back their lands for personal use.”

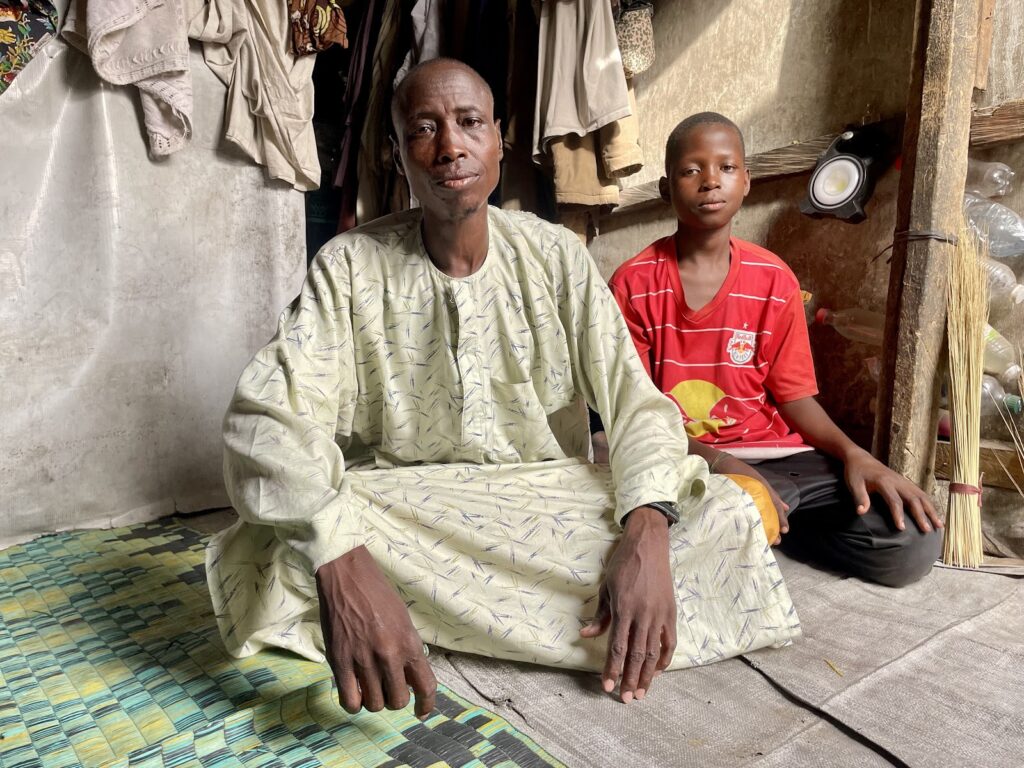

Bakaka Grema, 55, and his family are some of those rendered homeless by the development.

“We don’t know where to go or what to do. Our village is still destroyed and in rubles,” he said. “When our landlord issued us an eviction notice, I had to beg one of the family members to give me space in his house pending when things improved. Day by day, housing size is shrinking because everyone is assisting those that have been affected by eviction.”

At least 50 households have been affected.

Despite these setbacks, the people of Panamri remain resilient. They have adapted to their new reality, finding ways to support each other and rebuild what was lost, such as cultivating small plots of land and trading goods in the local market.

Grema Bukar, the community head, said they are ready to return to their original homes if the government guarantees their security.

Meanwhile, while IDPs at the Panamri makeshift camp do not pay to reside there, displaced families at the Biafra and Shuwari Five camps risk eviction if they default on rent.

In Biafra camp, situated at the bank of the River Ngadda along the lane of the busy market areas of Maiduguri, displaced residents are charged a monthly fee of ₦2,000. Most of the residents are displaced people who fled villages along the Maiduguri-Bama road because of the Boko Haram insurgency.

Forty-five-year-old Fati Sale and her husband must work hard, or else they will not be able to raise enough to eat and pay their rent. Her husband spends the day in Maiduguri Monday Market looking for hard-to-find work or doing menial jobs for little pay. She herself does petty groundnut trading around the market or in the camp.

She used to get assistance from relatives who lived in the town, but eventually, everyone who once supported her got tired of her relentless requests.

“Our needs are enormous, and this really affects us daily. We spend the little we get on food, and before we know it, the month will end, and we will be asked to pay our rent,” Fati said.

“My room was locked several times before because my rent was overdue.”

Umar Modu Mohammed, head of the displaced community at the Biafra camp, is uncertain about their future and is afraid landowners may soon evict them. There are over 200 households in the camp, and finding alternative shelter in Maiduguri is a daunting task, especially considering the high rent prices and limited housing.

“I am afraid of the prospect of being displaced yet again. We have already endured so much hardship and uncertainty since fleeing our home,” Umar said.

Aside from the challenges of paying rent, displaced residents in the Biafra camp face many other difficulties.

Food prices have soared, making it increasingly difficult for Fati’s family and others to afford basic necessities. The recent hike in fuel prices has further exacerbated the situation, as transportation costs have skyrocketed, making it harder for residents to access markets or employment opportunities in town.

With limited job opportunities, many struggle to make ends meet. This combination of factors has created a perfect storm of economic hardship for displaced families.

Umar lamented that humanitarian assistance stopped flowing about four years ago. “We are lucky that we are residing in the busy market area of the town. We embark on petty jobs around; if not, we would not be able to eat even once a week,” he observed.

‘I’d rather die here’

The story of Lidiya Inuwa reflects the struggle of many women whose husbands were killed by Boko Haram. She fled Chibok with her seven children four years ago after this incident and now lives in the Shuwari Five camp, where she pays for a roof over her head.

“My husband was ploughing the field while I was working on the farm,” she said, sharing a glimpse of her last moments with her husband. It was supposed to be just another day on the farm, but fate had other plans.

“Without warning, a group of terrorists descended upon us. They came out of nowhere, their faces twisted with malice and hatred. Before we could react, they surrounded us.”

She could not bear the pain of recalling the tragedy that befell that day. One of the terrorists disembarked from his bike and tied Lidiya up, immobilising her while she watched in horror.

“My heart pounded in my chest. I could do nothing but scream as they mercilessly slaughtered him right before my eyes. The sounds of his cries echoed in my ears long after they had left, leaving me alone in the field with our baby in a state of terror,” she said.

In the aftermath of the attack, she could not stay in the village because she was haunted by the memory of that fateful day on the farm. So she moved to Maiduguri and settled in a camp, hoping things would improve. But she has had to grapple with hardship and hunger as she tries to fend for herself and her many children. Still, she says, there is no going back.

“Life is not easy here. I pay ₦10,000 for the room we stay in. I can’t afford to take my children to school. There is inadequate food, and basic amenities like water and hospital are far from us,” she said. “But I would rather die of hunger in this camp than return to my village where the corpse of my late husband rests.”

Last year, HumAngle reported how some IDPs were given an eviction notice after years of staying in a location, after which they moved to the Shuwari Five camp. They face an uncertain future yet again. About two years ago, occupants of the camp lost two basic amenities, the school and health centre, because the land on which they stood was recovered by the owners for personal use.

Looking ahead

Amidst the relentless challenges of multiple evictions and the burden of paying for residence, the displaced communities residing at the Shuwari Five IDP camp have reached a breaking point. They have decided to leave the camp behind and seek refuge elsewhere on the outskirts of town, where they hope to live peacefully and without disturbance.

“There, we can access farmlands and be free from all the odds that restrain our lives every day. We have endured enough,” Zanna Rebo, head of the displaced community, told HumAngle.

He added that they have complained several times to the government about their need for a space to settle in, but they have yet to receive a positive response.

“There is nothing we can do,” Zanna said. “Our original homes are still not safe, and here is not our home. We feel neglected.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter