Mindless Murder Of Unarmed Fulani People By Vigilantes In Northwest Nigeria

There is a growing wave of extrajudicial killing targeted at Fulani people in Nigeria’s northwestern region as a result of ethnic profiling.

Ja’e Sanni, 50, sat soberly as he shared the story of how his son was killed. He never thought the case would make it to the public as there had been no media report on the incident. Today, he is glad his experience would draw attention to the extrajudicial killings of ordinary citizens by vigilantes fighting terrorism in Northwest Nigeria.

“Where should I start from?” he asked HumAngle during a visit to Sakajiki village in the Kaura Namoda area of Zamfara in March. “Life has been miserable since my son, Muhammed Sanni, was killed in January by vigilantes who claimed to have suspected him of being a bandit. Without a fair hearing, they shot and slaughtered him.”

Before his death, the deceased, a 25-year-old second son, always worked on his father’s farm. He had gone to the market to sell some of the farm produce when members of a vigilante group, known locally as Yan Sakai, slaughtered him because he was Fulani, his father said.

Ja’e recalled that his son was never a troublemaker and had on several occasions condemned the activities of terrorists in the region. “They first shot him with their gun,” he narrated. “Even when dying on the floor, he pleaded softly, denying being a bandit. But they did not listen. They grabbed his throat and slaughtered him with a knife.”

Muhammed’s death injected sorrow into their home. His mother developed a stroke as a result of the shock that followed and his other six siblings fear that their safety cannot be guaranteed in their hometown.

“I have heard people talk about ethnic profiling but never thought I would be a victim, let alone lose my son. I don’t feel happy hearing people call Fulanis bandits because not all Fulanis are evil. I’ve preached this, but the sermon has no place in vigilantes’ hearts. They do as they wish, and all I can cry for is justice. I wish to get justice for my son who was killed and those that would be lynched in the future because it doesn’t seem they will stop soon.”

Ethnic profiling and extrajudicial killings

Northwest Nigeria has, in the last few years, witnessed an upsurge of violence, which has led to huge losses of lives and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of persons in the region.

HumAngle understands that there are different narratives on what escalated the deadly violence in the region, but it is deeply rooted in the conflict between herders, who are mostly Fulani, and farmers, who belong to the Hausa and other ethnic groups. This conflict is worsened by a vicious competition for limited environmental resources.

The crisis later evolved into full-blown terrorism, with armed groups on motorbikes sweeping into villages, and highways, and then carting away livestock and anything else of value. They also storm communities at will and kill armless residents.

Large-scale weapon smuggling has also allowed criminal gangs access to sophisticated arms, as under-equipped local and federal forces such as police and military find it difficult to tackle the terror groups effectively.

The terrorists have multiple ways of making money, but kidnapping for ransom appears to be the most profitable. While a cow in Nigeria can fetch ₦200,000, the relatives of one kidnap victim can pay millions of naira as ransom.

In tracing the history of the armed violence, Murtala A. Rufa’i, a lecturer at Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, gave accounts of how Fulani herders are said to be on revenge killing missions for similar treatments meted out to them by Hausa farmers in 2011.

As the situation worsens, criminal elements who represent a low percentage of Fulani people have left a serious image problem for the entire ethnic group. The media have been particularly accused of stoking ethnic tension through their blanket labelling of criminal herders as “Fulani”.

Ethnic profiling has led to the murder of people identified as Fulani by vigilante groups. Just like Muhammed, the offence of many who have been killed for alleged involvement in banditry and terrorism was that they belonged to the ethnic group.

In Dec. 2021, Bello Turji, a terror kingpin who led attacks on various communities in the region, wrote to Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari and other state actors in Zamfara, expressing concerns over what he tagged the maltreatment of the Fulani ethnic group in the country.

He reiterated in March that his group was fighting in defence of the Fulanis against vigilante groups that attack, maim, and extrajudicially kill people from his tribe, forcing them to regroup in forests where they set up camps to unleash mayhem on vulnerable rural communities.

More extrajudicial killings

Aliyu Jahhi, 45, was choked with tears as he narrated how members of a vigilante group killed his brother and first son in his presence.

His 17-year-old son, Mumin, had just finished his secondary school education when he was killed. His 50-year-old brother was a taxi driver. The vigilantes attacked them at Gidan Katakare, in the Birnin Magami area of the state, claiming they had information that residents in the community had links with terrorists.

“My son and my brother were the ones who confronted them that we didn’t have any bandits nor their informants. They were displeased by the confrontation, and they started shooting sporadically at people in the village.” As Aliyu tried to give more accounts about the incident, tears started to build up in his eyes.

He said since his elder brother’s two wives were not working before he died, they have since struggled in getting sustenance. Aliyu now bears the burden of providing for the women and the eight children the deceased left behind. This is despite having six children and one wife himself.

“I am just praying to God to bring the insecurity to an end because many innocent people are suffering from the happenings. I have been displaced from my village, and all I want now is peaceful coexistence.”

Tukur Muhammed, 45, is another Fulani man in this state of despair. His 60-year-old father was killed in Nov. 2021 for allegedly being a ‘godfather’ to bandits. The pain of losing a loved one could still be felt in her voice.

“Vigilantes killed him because of a rumour that he was sponsoring bandits. They used Daga [knife] on him and dumped his remains on the street,” he said.

Displacement

Usman Mesaje, 40, left Anka because of the fear of being attacked by vigilantes after repeated blackmails and threats to his life. He currently lives in the Gummi area of the state with no prospect of returning home soon.

“I have long left home because of insecurity, and we are being targeted by people who believe that those of us from the Fulani tribe are criminals and evil. I left home a day after my friend was killed last year. I have since brought my family to an IDP camp here in Gummi for safety,” he said.

“The security agencies should take necessary action because we cannot continue like this. We are the most vulnerable and no one cares to listen to us. The Fulanis are coloured badly but no one talks.”

Azeez Rabiu had to leave his home too. He lost his taxi and other valuables when terrorists attacked his village in Dec. 2021. By early January, he was evicted alongside others by vigilantes who claimed to be fighting the menace.

“My only offence was that I am a Fulani man. An entire Fulani community in Kaura faced massive eviction by vigilantes who claimed that they were accommodating bandits. Our problem is complex because as we face eviction by vigilantes who dislike us for being Fulani, the bandits do not also spare us when carrying out their attacks.”

‘Why we are attacking Fulanis’

Nafiu Muazu is a 30-year-old taxi driver from Barkaji in the Kaura area of Zamfara. The Hausa farmer left farming for the taxi business after bandits took over his farm in late 2020. He has also been displaced from his village due to the activities of the terrorists since January.

He justified the extrajudicial killings of Fulanis, saying, “they are evil and have caused death in many homes. I no longer have a home because of the activities of Fulanis and I feel like attacking them personally anytime I see them but I do not have the power to do so. I’m encouraged by what the vigilante members are doing. We are glad that vigilantes are attacking Fulani communities.”

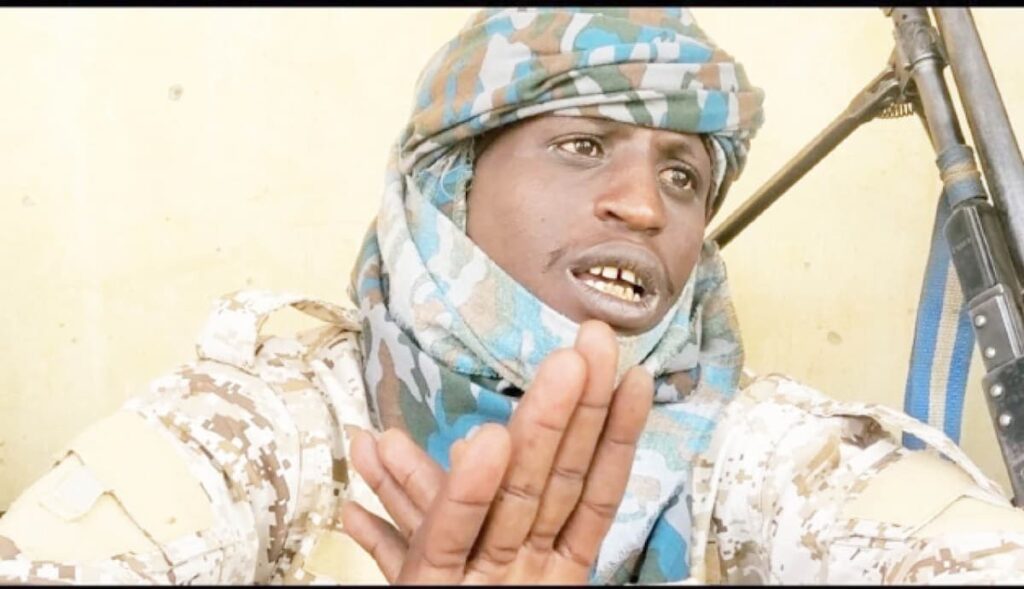

Goje Muhammed, one of the leaders of the vigilante groups in Yanbuki, a village in the Zurmi area of the state, also justified the attacks. He argued that his men and other vigilante groups were helping to fill the gap the authorities had failed to address.

“What do you expect of us? To fold our hands and allow bandits to continue to kill our people and also watch them take over our village? Since security personnel are finding it hard to combat them, we must step in to help our people to save our lives and properties,” he said.

He added that it is their belief that most of the terrorists are Fulani and they know one another.

“They have connections with bandits and I will remain undisturbed by the blackmail that we are killing people extrajudicially.”

Abuse of fundamental rights

Extrajudicial killing is an infringement of the citizen’s right to life and violation of various laws, both local and international.

Human rights lawyer Ademola Owolabi told HumAngle that the killing of Fulanis by vigilantes and militia groups is a violation of the rights to human dignity as contained in the country’s constitution.

“Life is sacrosanct and must not be taken in any way outside the provision of the law. The challenge is that all manner of crimes are given tribal colouration and as such anybody can just label any group which is wrong,” he noted.

“I would have thought the Nigerian government would handle this better in its early stage before getting to a stage of uncontrollable killings. It is unfortunate that even the victims of bandit attacks are now being victimised. Crime has no tribe and the government must ensure that crimes do not go unpunished. No lesson will be learnt without deterrence.”

Another lawyer and rights activist, Adesina Ogunlana, observed that those involved in extrajudicial killings undermine state authorities. “What is the purpose of governance if we allow that?” he asked. “Mob rule is not governance. It would only lead to retaliation and increase lawlessness.”

In April, Bello Abdullahi Bodejo, the President of the Fulani socio-cultural association, Miyetti Allah Kautal Hore, also condemned what he called “genocide being perpetrated against Fulani herders by the Hausa in the guise of securing lands in some Northern states.”

HumAngle contacted Zamfara’s state police spokesperson, Muhammed Shehu, for comments on our findings but he told our reporter to call back. He has since refused to respond to calls and text messages.

Meanwhile, Zailani Bappa, chief press secretary to the state governor, noted that the issue in Zamfara is “complicated because some Fulanis have decided to be criminals”.

“All the people killing and kidnapping are not doing it in the name of Fulani. They are just criminals. We have tried to negotiate between the Hausas and the Fulanis so that all these killings can stop but these criminals will not stop doing it,” he said.

“Truly, there are people who are informants to bandits but the vigilantes sometimes try to take laws into their own hands and the state government has been trying to stop this. The government at a time disbanded vigilante groups from operating in the state but it later became necessary that they have to complement the police. They are now undergoing training on how not to take laws into their own hands.”

Asked about the government’s efforts to stop the killings, he replied that the incidents had to be reported first before they are investigated. “Sometimes we only read these things in newspapers. If we have genuine allegations against vigilantes, it would be investigated.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter