Locals Stand To Gain As Lake Chad’s Military Alliance Steps Up War Against Insurgents

Lake Chad's military coalition fighting Boko Haram and ISWAP has made inroads in the past weeks. If it succeeds in securing the waterways, islands, and inland communities, this could help the local population to resettle and harness the area’s agricultural resources.

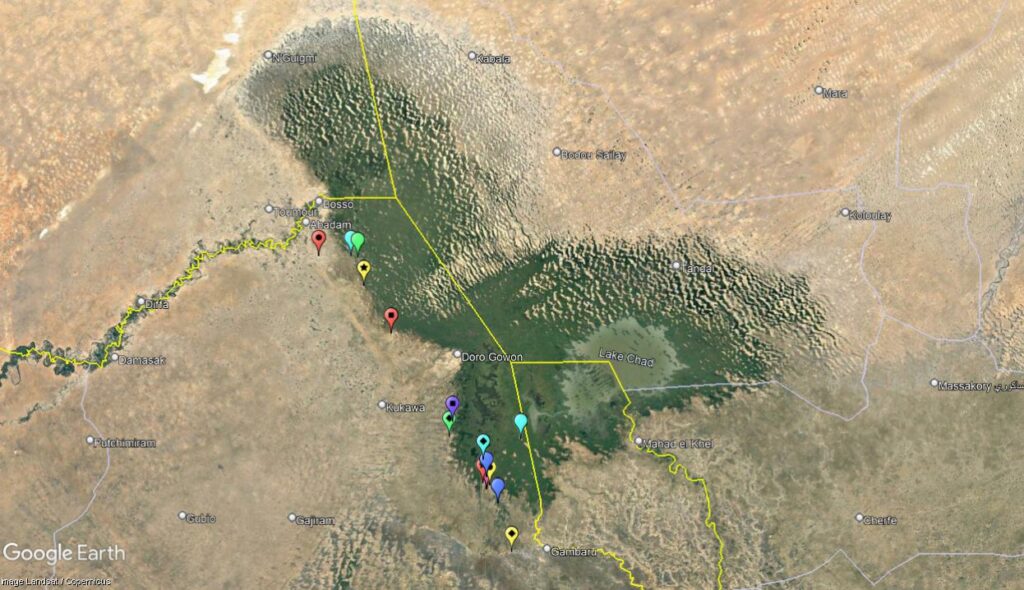

The Lake Chad countries’ Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) is making inroads as ground and amphibious forces backed by air support sweep through insurgents’ spheres of influence, particularly around the islands and lakeshore areas in northern Borno, Northeast Nigeria.

In the past weeks, the military coalition has intensified offensive missions and patrols, consisting of MNJTF assets mustered from Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon. These have also involved Nigeria’s domestic counterinsurgency forces operating in the northeast and the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF), a local militia assisting state forces.

The ongoing campaign was preceded by weeks-long operation in Dec. 2021. In January, the mandate of the regional force was renewed, allowing it to continue with the coordination and implementation of joint operations.

Generally, the MNJTF, which is headquartered in the Chadian capital of N’Djamena, comprises personnel from Benin and sectional headquarters in Baga-Sola in western Chad, Baga in northeastern Nigeria, Diffa in southeastern Niger, and Mora in Far North Cameroon.

What is going on?

Operational briefs and open-source information from Google Earth satellite imagery help understand the range of the operations. They also highlight the challenges associated with the terrain.

According to an April 19 briefing, the MNTJF cleared some locations including Arina Woje and Zanari, which reportedly served as a major fabrication workshop. Others were Abadam, Arege, Asagar, Doron Lelewa, Garere, Kerenoa, Kolaram, and Wurje. The Task Force also captured and destroyed equipment including an OTO-Melara Mod 56 105mm artillery piece, several boats, motorcycles and bicycles, alongside enablers such as fuel dumps, Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) making factories and bunkers.

The soldiers were said to have conducted a clearance patrol in the Fedondiya settlement where they discovered non-operational and cannibalised military and civil vehicles. The camp also had grinding machines and vehicle fabrication tools that indicated it hosted an IED workshop camouflaged to prevent detection from the air. In the course of the operation, soldiers encountered four vehicles rigged with explosives.

A subsequent briefing on April 21, revealed that Nigerian and Nigerien forces stationed at the Forward Operating Base (FOB) in Arege conducted a clearance operation in coordination with the Air Force, which carried out air raids in the vicinity of Tumbun Fulani and Tumbun Rago. The airstrikes were followed up with ground units advancing to Tumbun Fulani. They, however, could not access Tumbun Rago due to the marshy terrain.

In another incident, Nigerien troops on patrol around the Ngagam–Kabalewa and N’guigmi areas destroyed two gun trucks and recovered several arms and ammunition after a firefight with a group of insurgents.

The MNJTF on April 26, disclosed that Nigerien troops engaged in a fierce firefight in the general area of Kaji Jiwa which led to the killing of several insurgents and the recovery of 15 AK pattern rifles, two belts of 222 ammunition, and 179 cartridges. An infiltration attempt within Niger’s area of operation near Doutchi was pushed back by the Air component and ground forces. After that encounter, one gun truck was recovered while three others were destroyed.

According to the Task Force, Nigerian and Nigerien contingents in Arege continued with clearance operations to dominate the area around Fedondiya and Arege. The report also stated that Cameroon’s amphibious Task Force had stepped up riverine patrols and assaults against insurgents in the general area of Tchol and Chaka.

On April 30, Nigerian and Nigerien soldiers stationed at the FOB in Arege continued patrols to put pressure on the insurgents. With air support, the unit was able to access fortified positions in the vicinity of Tumbun Rago. The raid led to the recovery of 12 AK pattern rifles, one 60mm mortar, and ammunition of different calibres, while five gun trucks and a truck with supplies were destroyed. An abandoned REVA Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) was also recaptured.

The Task Force disclosed that the Cameroonian soldiers in Wulgo carried out a clearance patrol in the general area of Chikingudu. Similarly, Cameroon’s amphibious unit in Darak continued riverine patrols and cleared the villages of Bourame, Kirta Wulgo, Magoume, and Tcholl. On May 14, the MNJTF revealed the deployment of the Chadian contingent in Malam Fatori, headquarters of Abadam Local Government Area which borders southeastern Niger and southwestern Chad.

The latest Task Force brief published on May 21 disclosed that Nigerien and Nigerian soldiers carried out clearance operations around Ali Jimari, Dogon Chuku, and Tunbum Rago. Nigerian and Chadian soldiers have equally kicked off clearance operations from Monguno and cleared several settlements including Ali Sherifti, Daban Gajere, Daban Karfe, Daban Masara, Doron Naira, Grada, Kwatan Maishayi, Sabon Tunbu, Tumbun Buhari, and Tunbun Abuja.

ISWAP has resisted the military incursion through diverse tactics, including the use of IEDs buried on routes and a surge in suicide vehicle-borne IEDs counterattacks, in addition to engaging in firefights. The insurgents also simply withdraw and avoid contact with the approaching troops, an approach that allows them to return to the same spots — although the military usually destroys the support infrastructure left behind such as vehicles, workshops, and shelters.

It’s unclear if the operation would also seek to secure areas under the influence of Boko Haram’s Bakura group.

What’s different this time?

The military coalition is leveraging the availability of offensive capabilities to prosecute the campaign. These include airborne platforms drawn from the fleet of the national forces for surveillance, bombing runs, and transport. However, third party contractor aircraft make up an important chunk of the Task Force’s air transport capability.

Similarly, the campaign is benefiting from the presence of more Nigerian tracked and wheeled armoured vehicles, particularly the CS/VP3 Bigfoot Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) and Type 89 armoured fighting vehicles (AFV). Another advantage is the increased involvement of mobile riverine forces using shallow boats that allow the soldiers to operate, fight, and move along the waterways. These boats include the Gator Tail watercraft which was employed during the U.S. Naval Small Craft Instruction and Technical Training School training of regional forces.

The ability to sustain surveillance and patrol, particularly against ISWAP’S land and riverine force, is essential for securing the wetlands and islands to pave the way for socio-economic activities. This will require more investment in expanding the MNJTF’s shallow and muddy water patrol capability.

Impact of the offensive

One important development on the security environment is the reactivation of the FOB in Arege near the shores of Lake Chad, which provides a suitable platform for patrols and restricting the insurgents’ movement. FOBs such as Arege and Metele were overrun after ISWAP’s persistent attacks that led to a reduction of the military’s footprint in hinterland communities as well as the formation of the super camps.

The capacity of the regional and national forces to garrison areas that have been secured and dominate the environment could reduce the ability of insurgents to exploit the local resources, economy, and population. It will also create the conditions that will facilitate humanitarian interventions, restore and expand livelihood activities, and rebuild communities.

This is important, especially because of the Borno state government’s policy to close camps, rehabilitate destroyed communities, and relocate displaced persons back to their hometowns or locations near their original communities. Malam Fatori, one of the crucial locations for the current security operations in Lake Chad, is also where officials have begun the process of rebuilding and returning displaced persons.

About 500 households (4,000 individuals) from Bosso in the Niger Republic have already returned to the town. It was initially captured by Boko Haram in 2014 before it was recovered by soldiers from Niger and Chad the following year. It was subsequently deserted and then recaptured in 2016 by the Nigerian Army; but it remained a volatile area with a high level of security risk.

Lake Chad’s conflict trajectory

The conflict in the region has morphed since ISWAP invaded Sambisa, the stronghold of Boko Haram, which climaxed with the death of the group’s leader, Abubakar Shekau. The situation has led to the expansion of ISWAP. Its attempt to absorb Boko Haram members has, however, suffered setbacks as some fighters refused to join its rank.

This has resulted in over 51,000 combatants and non-combatants, consisting of women and children, fleeing the hinterland and surrendering to the authorities. Other fighters have opted to mount resistance around the Mandara mountain range near the border with Cameroon while the Lake Chad group have maintained hostility against ISWAP.

The Islamic State franchise’s pledge to Abu Al-Hassan Al-Hashimi Al-Qurashi in March showed strategic changes that have taken place within the group, including what appeared to be the adoption of a semi-autonomous governance model. The pledge consisted of subgroups in Lake Chad, Faruq (Alagarno forest-Timbuktu Triangle enclave), Kerenoa/Kirenowa (an area in Marte near the fringes of Lake Chad), Banki (a former Boko Haram area of influence near the Cameroonian border), and Sambisa.

Last month HumAngle analysed the military operations in Sambisa and the insurgents’ cat-and-mouse game with security forces using publicly available satellite images and open-source information. During recent operations in the area, the soldiers were able to make a deep push into the enclave leading to the discovery and destruction of equipment and shelters.

ISWAP’s offensive doctrine has also mutated as a result of the impact of airstrikes and ideological guidance. The group has initiated an urban campaign associated with attacks involving small squads and explosive devices to hit locations outside its centre of gravity.

This disturbing phase creates new risks for civilians and security forces.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter