Life For The Displaced Woman When Her Husband Goes Missing

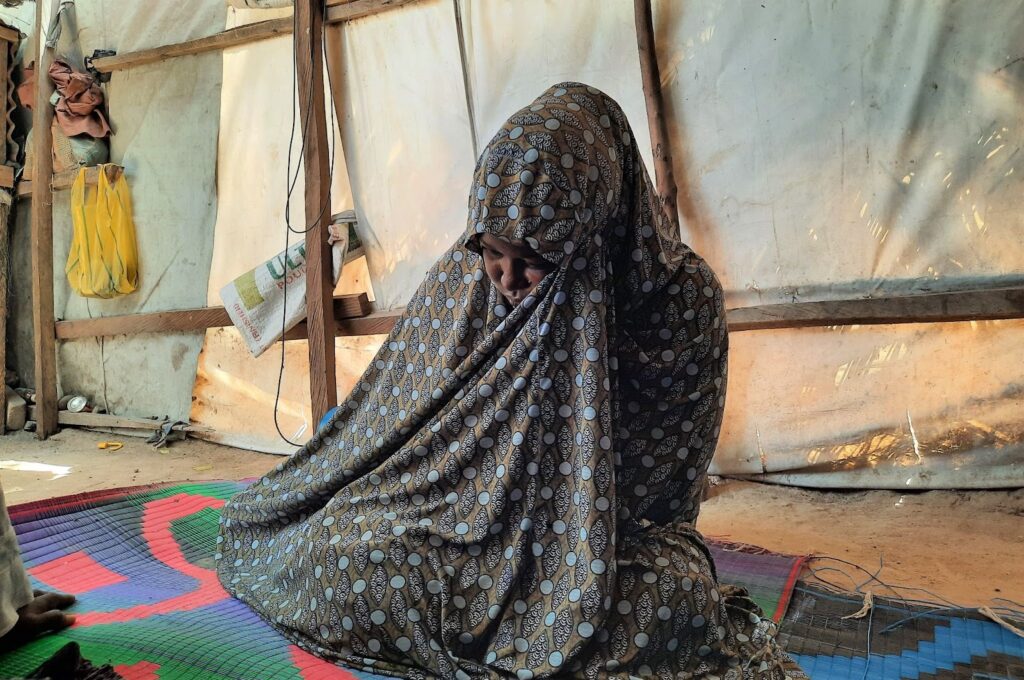

Hajja Hawwah faces discrimination and hardship as a single mother displaced by Nigeria’s war with Boko Haram.

When Hajja Hawwa Saleh arrived in Maiduguri in late 2015 as a displaced woman, there wasn’t enough food for her and her infant daughter. So she would go to the market and gather leftover grains from the dirt, wash them, and cook. She also packed the discarded parts of slaughtered livestock, selling some and eating the rest.

Life was especially hard because her husband, Saleh Abba, was not with her. Several of her misfortunes could be traced to Saleh’s disappearance months earlier.

“Later, they told me if I prepared the grains for grinding, they would pay us,” Hawwa, 25, says, referring to the traders at Maiduguri’s Custom Market. “We started going, three of us, and then many women joined us. We went through all this because we had no husbands.”

At the Kawar Maila displacement camp, an international humanitarian organisation gave her a monthly food allowance of ₦5,000 ($11), which wasn’t nearly enough. It was that small because she told them she only lived with her daughter, she explains. It was the aid’s meagre size that forced her to labour and scavenge at the local market. Meanwhile, she saw other families receive between ₦20,000 and ₦50,000 ($114) from the same organisation, depending on their size. She could not complain, fearing she might lose the support.

Eventually, that money stopped coming anyway and she was forced to think of new ways to earn a living. “I had to learn how to knit caps,” she says. “But sometimes people don’t buy because they complain that I didn’t make them well.”

She insists that if Saleh were around, not only would they have received more aid, but they would both work and share the family’s responsibilities. Life as a displaced person with a partner is already difficult enough, let alone without.

So what happened to Saleh? Hawwa is not sure.

They met and got married in Kumshe, a community in eastern Borno that’s only a few kilometres from the Cameroonian border. With his wheelbarrow, Saleh worked as a baggage carrier in Kusuri, Cameroon, and Chad’s N’Djamena. He also engaged in seasonal farming in Nigeria and provided for the family from his diverse income. “We lived happily,” Hawwa recalls with nostalgia. “There was no misunderstanding between us. Life was good.”

Three years into their marriage, shortly after she had her daughter, their life lost its calm.

One night during this period, Boko Haram terrorists, about nine of them on motorcycles, attacked the community and killed three residents. The next day, Nigerian fighter jets cut through the sky. The insurgency, which had erupted in Maiduguri years earlier, was finally knocking on their doors. Everyone was afraid. People started leaving in case the terrorists returned — or worse, the jets, especially if this time they stayed and bombed the houses.

The residents moved to neighbouring villages. Most of the men stayed in Masamari. Hawwa left her husband here and travelled to Dikwa in early 2013 with her mother. But the violence soon spread there as well. Hawwa’s parents travelled to Gamboru. But they got stuck, again due to Boko Haram’s activities, and could not return. They had to cross into Fotokol, a Cameroonian town about 300 metres across a river from Gamboru.

Hawwa rejoined Saleh in Masamari and together they moved to another village, Muluwuta. Saleh built a hut for the family and they settled there for 10 months. He made some money from fishing and collecting firewood. But life in Muluwuta was difficult because the area too was under Boko Haram control. The terrorists would beat people for felling live trees. So, again, the couple planned their escape.

“We had agreed that I would go first and leave him behind whenever there was an opportunity. So one day, I escaped in the company of my neighbour’s wife. We came to Umawa in Cameroon and two days later, my husband went to Banki.”

She never saw Saleh again.

Tens of thousands of Nigerians have gone missing in circumstances related to the insurgency too. According to the latest estimate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), as many as 25,000 at least remain missing — the largest number across Africa.

“I learnt he wanted to make the journey to join us. Someone who left Muluwuta said they saw him coming with his bicycle. I didn’t hear from him since that day,” Hawwa says.

In Cameroon, the military transferred the refugees to Limanni, squeezing over 20 people into a small room at night.

“It was congested and we urinated in a plastic bucket. The room had no door and they put us in through the window. In the morning, they would keep us in a house. After five days, they took us to Banki where we stayed for five months. Then they took us to Bama prison in late 2015.”

People were usually taken to the prison for screening. Most of the detainees were released and taken to a displacement camp after a few days. But Hawwa and other women who didn’t have their husbands with them spent a month at the facility.

“They kept us there to cook for them, accusing us of leaving behind our Boko Haram husbands in the bush. When they found that we were innocent, they transferred us to an IDP camp and after a month, I finally came here to Maiduguri.”

The situation at the Bama camp was dreadful too. People, especially children, died in droves due to malnourishment and starvation.

Saleh is a tall, dark-skinned man. Hawwa says he was kind not only to his family but others as well. Even though her brother also lives in Maiduguri, they usually go many months without seeing each other. “—So, I always think about Saleh because I live alone.”

Amina, their daughter who is now seven years old, asks for her father every now and then, and Hawwa would tell her not to worry because “he would come back”.

She herself would walk on air if he showed up. Saleh’s return would not only mean she could share burdens with him, but it would also help her avoid the discrimination she currently faces as a single mother.

“In Bama, they interrogated us too much, thinking they would make us confess we were Boko Haram members. They gave us food only once in a day,” she says.

“Here in Maiduguri, some people used to accuse us of prostitution and abortion. One even went on the radio about two weeks ago to say so. That we are here without husbands and go to town to sleep with men. They called me, and I told them that maybe it is better we go to that radio station to state our own side. We went there and told them that the person who accused us of killing children in the toilet, let him come and prove that we committed those things.”

Hawwa cleans tears from her eyes after narrating this, her voice subsequently becoming hoarse.

Asides getting her husband back, her only other wish is to see Amina educated and with a bright future ahead of her. The young girl used to attend an Islamiyyah school, but hasn’t gone in several months because she could no longer afford the fees.

“The challenges are too much,” Hawwa whimpers. “It’s why when you sit in the night, you can’t even sleep.”

This report was produced in partnership with the Open Society Initiative for West Africa (OSIWA) under the Missing Persons Register’s Population and Amplification Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter