In Adamawa, Peacebuilding Begins on the Football Pitch, in Classrooms, and at Townhalls

A Boko Haram attack in 2012 led to a series of reprisal attacks within Nassarawo in Yola, a community where Muslims and Christians once co-existed peacefully, and other parts of the state. Young people came together to repair the broken trust.

When Boko Haram attacked a religious gathering in Nassarawo, Yola, the capital of Adamawa State, northeastern Nigeria, and killed 12 persons in January 2012, it ignited deep-seated anger, fear, and suspicion. The incident led to a series of reprisal attacks within Nassarawo, a community where Muslims and Christians once co-existed peacefully, and other parts of the state.

Schools closed, businesses shuttered, and families fled, some never returning.

“That evening changed everything,” Kauna Hamman, a resident of Yola, recounted. “We watched a quiet neighbourhood with a history of coexistence, switch to distrust and separation.”

The event, which was one of several other ethno-religious crises in Nigeria that have claimed hundreds of lives, left Kauna wondering what could be a way out. “If violence can divide us so quickly, can peace not bring us back together?” she asked.

Kauna eventually joined the North East Social Innovation Fellowship (NESIF), an initiative aimed at countering violent extremism in the region. During the fellowship, she met nine other young people—each, like her, from communities devastated by the Boko Haram insurgency. Together, they shared a deep conviction: that marginalised communities hold the power to drive their development and transformation.

They founded Strategy for Peace and Humanitarian Development Initiative (SPeHDI) in 2018.

Adamawa State is home to a rich blend of cultures, traditions, and religions. While the relationships between the various religions are often defined by peaceful interactions, moments of conflict, like the 2012 incident in Nassarawo, have periodically strained these ties.

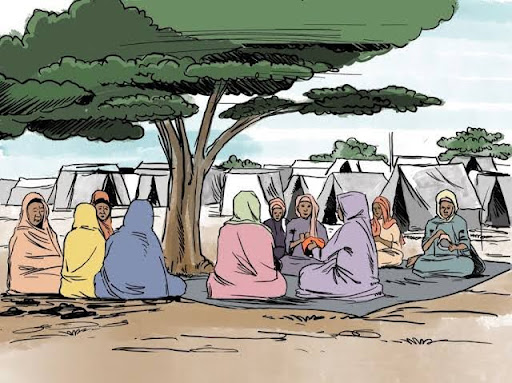

SPeHDI’s mission centres on promoting communal peacebuilding and preventing violent extremism through approaches that integrate human capital development, social empowerment, and education. The organisation emphasises core values such as honesty, humanity, transparency, participation, and accountability, believing that these principles are essential in cultivating an environment where peaceful coexistence can flourish.

“Through engaging communities in interfaith dialogues, sporting events, and ‘catch them young’ programmes, SPeHDI equips children, youths, and women with the necessary conflict resolution and negotiation skills to settle disputes amicably, while also providing them with a source of livelihood,” Kauna, who serves as the Executive Director of SPeHDI, told HumAngle.

Moreover, SPeHDI actively counters extremist narratives by providing alternative perspectives through social media campaigns, pamphlets, and targeted sensitisation programmes. These efforts address underlying issues such as drug abuse, lack of education, and unemployment, factors that can drive vulnerable populations towards extremist ideologies.

Operating at the state and local government levels, the organisation’s grassroots initiatives aim not only to enhance social cohesion but also to empower local communities to participate actively in their development.

‘Football for peace’

In September 2021, the initiative hosted an inter-street football competition in Bekaji, a community in Yola, to mark the International Day of Peace.

“It was inspiring to see both Muslims and Christians coming together to play football,” said Yakubu Joel, a resident of Bekaji, who participated in the competition. “This event makes us reflect on our commonalities and shows that when we set aside our differences, we can all contribute to a stronger, more united community.”

Nearly four years on, the impact of that tournament still resonates. Residents told HumAngle that sports have continued to serve as a unifying force in Bekaji.

“We are benefiting from the football jerseys the organisation gave us in 2021. The jerseys are the official sports wear for the Bekaji football team to date, and it is worn by everyone, regardless of their faith. It is a testament to the unity and harmony SPeHDI has instilled in us,” said Dyangapwa Heman, another resident.

HumAngle has previously reported on other community-led initiatives that use sports, especially football, to bridge divides in conflict-affected areas, such as Jos in North-central Nigeria.

“For me, peace is not merely the absence of conflict—it’s a process of healing and rebuilding trust,” Kauna said.

Between 2021 and 2023, SPeHDI organised three week-long annual sporting events across Yola North, Numan, and Girei local government areas. The events drew large youth participation from various religions, not just as players, but also as cheerleaders, spectators, and match officials.

“Through the engagement of different faiths and involving women and youth in our peace initiatives, we work to dismantle cycles of violence and lay the groundwork for lasting justice and community healing,” she added.

‘Catch them young’

Although children often bear the brunt of conflict and its aftermath, they are frequently overlooked in peacebuilding and conflict resolution efforts.

Recognising this gap, Kauna and her team launched Catch Them Young, a programme designed to instil a culture of coexistence among children by equipping them with conflict resolution skills from an early age. As part of the initiative, SPeHDI has established peace clubs in 10 secondary schools across Adamawa State, with several students participating.

At the Lutheran Junior Seminary School in Mbamba, Yola, Emmanuel Bapatu, a former principal, told HumAngle: “Students meet every Wednesday and Friday from 4 to 5 p.m., where they are equipped with essential conflict resolution and dialogue skills. It’s a vital step toward fostering a peaceful, drug-free environment.”

Tessy Mark is one of the students impacted by the programme. She was in Primary 5 when SPeHDI first introduced “Catch Them Young” to her school. Now in JSS 3 at Colonel Isa Memorial College, Yola, Tessy reflected on how the lessons have shaped her behaviour.

“Whenever I am angry or pissed at someone, I don’t just react immediately,” she said. “What I do is leave the place, calm down, and come back later to talk about the situation and settle it. I’ve applied this for a while now, and it has been working for me.”

‘It is a gradual process’

Building peace, especially in conflict-affected communities, is never without its hurdles. SPeHDI’s management acknowledged that their journey, though marked by hope and determination, has faced numerous challenges. Internally, the team continues to navigate the task of ensuring every member aligns with the organisation’s core values.

“Recruiting and retaining staff who genuinely reflect our community’s diversity is a constant challenge,” said Benjamin Nathaniel, the organisation’s Human Resource Manager. “We strive to ensure that our team embodies the trust and commitment our work demands, but it’s not always easy when expectations are high and there’s no external source of funding.”

SPeHDI is mostly self-funded, according to Meki Maksha, the initiative’s Head of Procurement. He pointed out the resource constraints the organisation regularly grapples with.

“Cost-effectively securing essential supplies often puts us in a tough spot,” he said. “We have to balance our limited resources with our goals carefully.”

These internal challenges not only strain the organisation’s capacity but also test its resolve to uphold the standards required for meaningful peacebuilding.

Externally, working with communities that have endured prolonged conflict presents its complexities.

“Many community members are understandably sceptical,” said Kauna. “They have seen promises broken before, and healing deep-seated wounds doesn’t happen overnight. Building trust in such an environment is a gradual process, and we sometimes face resistance simply because of past disappointments.”

This story is done in collaboration between HumAngle Media and Africa Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) as part of a project amplifying transitional justice efforts in North East Nigeria.

In January 2012, a Boko Haram attack in Nassarawo, Yola, triggered significant communal unrest and division in Adamawa State.

Kauna Hamman, witnessing the erosion of peaceful coexistence, co-founded the Strategy for Peace and Humanitarian Development Initiative (SPeHDI) in 2018. The organization's mission is to promote communal peace through education, interfaith dialogues, and empowerment, focusing on countering violent extremism and building bridges between divided communities.

SPeHDI organizes initiatives like inter-street football competitions and the "Catch Them Young" program to foster peace among children and youth, equipping them with conflict resolution skills. While they face challenges in resources and community skepticism, the organization remains committed to long-term peacebuilding in conflict-affected areas.

Successful programs, like those in Bekaji, have demonstrated the potential for sports and educational initiatives in uniting diverse populations and facilitating healing processes.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter