‘I Could No Longer Feed, Care For My Family After Our Resettlement’

An IDP speaks on how his suffering worsened after the Borno state government ordered the closure of IDP camps in Maiduguri and why he had to return.

When he lived at the Bakassi camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Maiduguri, Borno state, Mohammed Muhammad, could still go out to the town and do menial jobs. Through this, he earned some cash to support his family.

Though his family lived a life of struggle, the opportunity he had to go out every day to make money eased their suffering. An ‘extra kobo’ a day makes a lot of difference for IDPs, many of whom depend on periodic food donations that are usually inadequate.

At first, Mohammed said, it was a thing of joy for him. He was excited to receive the ‘good news’ of returning home after about seven years of displacement.

But no sooner had they arrived in Monguno town than he realised that his ancestral home was not the way he dreamed it would be.

“Everything looked, unlike the way it was seven years ago. There are more camp shelters than the normal houses; what I saw disappointed me and stole my excitement.”

Surrounded by a dug-up trench and parapet, Monguno is now a mega camp for internally displaced people whose remote villages and hamlets are still unsafe.

“You have no freedom in Monguno as it used to be; everyone is choked up within the town with little space for any form of commercial activity,” Mohammed observed.

“We all are confined within the town, and venturing into the bush for any form of activity may mean death from the marauding Boko Haram terrorists. People are being killed every day for daring to go far away from the town – and you won’t blame them because they are hungry.”

The Borno state government says it has so far returned about 130,000 IDP households to their respective communities in furthering its programme of closing camps in and around Maiduguri. It has also halted the supply of food by nongovernmental organisations to the IDPs, including those in unregistered camps within host communities.

Before he became displaced, Mohammed was a prominent beans farmer. After returning home, he tried to go back to this occupation. “But it was not possible due to strict land restrictions and control by Boko Haram,” he said.

“There is serious hunger in Monguno because many people still depend on aids, which don’t come as they used to. Things sold there are very expensive and in no time the little money given to us by the government when we were leaving Maiduguri got finished.”

Asides from hunger, people in the town live in fear of possible attacks by Boko Haram.

Mohammed felt he had no choice but to rerun his family to Maiduguri where he managed to rent a room to live in.

His experience is similar to that of Modu Bulu. He had also been ecstatic to return home to Kukawa, where he was a successful timber merchant before he became displaced. His displacement camp was closed in January. But when he got to Kukawa, he realised his family had better chances of survival in the Borno state capital. So they came back.

HumAngle has received accounts from returnees who said they had to pay taxes to insurgents from their harvests in places like Kukawa which are still under the control of the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) group. “I could not meet up with the tax I earlier agreed to pay for allowing me to cultivate a piece of land, and we all know that defaulting on their tax means grave danger. So I had to run,” one of the returnees recently told HumAngle.

Resettled IDPs in various parts of the state continue to face harsh conditions including the loss of livelihoods, extreme hunger, and attacks by terrorists.

The safe return to Maiduguri was a relief to Mohammed and his family even though the situation had changed compared to when they were welcome at the IDP camp.

“I tried to do a menial job but it was not forthcoming because every job seemed taken,” he said.

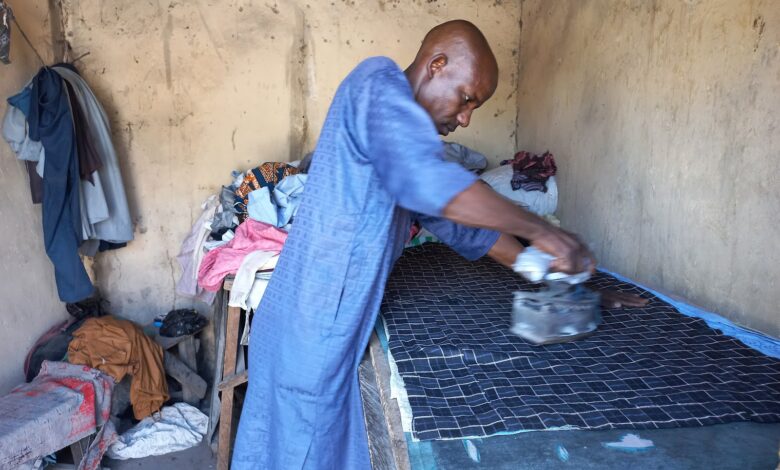

“I later saw an old Gwoza man who runs a very small laundry joint, and I begged him to let me work for him so that I could get something to feed my pregnant wife and our child.”

He said the laundry, though mostly patronised by the locals, still affords him between N200 and N500 daily “which I normally use to buy small food and ingredients and take home.”

“But out of that meagre income, which is not enough to feed with, we still have to contend with the outrageous amounts landlords take for a room here in Maiduguri,” he said.

“We pay the landlord about N2000 monthly for a small room. Sometimes my wife and I would go to bed in hunger because the food we got can only be okay for the child.”

He said he still needed support from the government in the form of food supplies and soft loans to start some business.

“I swear by God, people are hungry, especially in this Zajeri suburb. People are dying of hunger. We need support from the government. We need food and some economic support. The government should also kindly take food to people in Monguno because they are seriously suffering there.”

This report is produced in partnership with the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD), West Africa.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter