Hundreds Of Farming Communities Affected By Protracted Conflict In Southern Kaduna (Part One)

What most frightens Alhaji Kabiru Ahmadu, if you ask him, is the impending hunger and deepening impoverishment threatening the survival of the larger Southern Kaduna population this year.

The Kasuwan-Magani farmer becomes depressed whenever he thinks about the recurring clashes with no end in sight, which have been discouraging residents of farming communities from venturing to the field to grow food, even if little for subsistence.

Harvests have drastically declined over the years due to high insecurity especially at the outskirts of the communities during the cropping and harvest seasons. Farmers fear that if they visit their farmlands, they will be killed, maimed, or kidnapped for ransom.

Alhaji Ahmadu, who resides in Kasuwan-Magani, Kajuru Local Government Area, used to grow 70 100kg bags of maize, 50 100kg bags of rice and 30 100kg bags of soybeans before 2011. At the time, he recalls, he was even barely counted among the medium-scale farmers of the community.

Now he barely harvests 20 to 35 bags of those crops, depending on how many trips he is brave enough to make to the farm. He occasionally gets solace from herder-farmer and communal peace meetings organised by the state government, faith-based and community peace committees, and his religious doctrines.

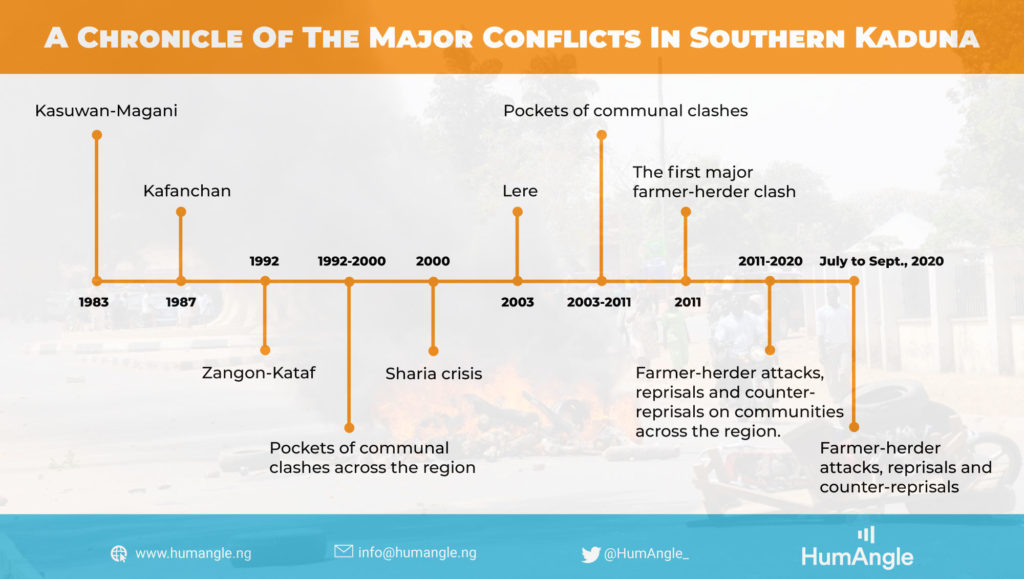

For about 37 years, the eight local government areas in the Southern Kaduna senatorial zone of Kaduna have been grappling with violent communal conflicts. These conflicts have assumed multiple colorations to, allegedly, suit the interests of racketeers and manipulators.

With attacks, reprisals and counter-reprisals, especially from 2011 to 2020, rising insecurity has plunged the region’s populations into hopelessness by weakening social and economic life as well as the once enviable unity among the multi-religious and ethnic communities.

Especially bearing the brunt and grave economic consequences of these violent conflicts are Sanga, Kaura, Kauru, Zangon-Kataf, Jema’a and Kajuru local government areas.

Most farmers in Southern Kaduna, as is the case with most other Nigerian societies, practise subsistence farming. They grow the little that barely lasts them until the onset of the next cropping season.

With no other substantial cash-yielding economic ventures, most farmers sell a substantial percentage of their farm produce to earn cash for other domestic needs and end-of-year festivities.

By the peak of the dry season, especially in April and March, they seep into the bush to hunt for whatever could complement their earnings from subsistence farming.

With the spike in insecurity, orchestrated by the persistence and rise in attacks, reprisals and counter-reprisals and, of late, kidnappings for ransom, farming and hunting activities have increasingly become difficult.

According to a prominent indigene of the region, “It may not be an exaggeration to say that about 3,000 farming communities have been affected with hundreds of thousands of their members displaced.”

“Yes! When you practically consider the population of displaced people from attacked villages, especially those who migrated, and are still migrating, to found new settlements in Kaduna and other urban centres, you will be inclined to see the figure in that region,” the indigene said.

A prominent community leader in the region, who also wished for anonymity, however, disputed this, describing the estimate as “clearly preposterous”.

He said, “In spite of the fact that we are devastated by the economic consequences of the crisis on our region, we should give credible facts and figures on the prevailing situation here.

“Consider the spread of 3,000 communities on the Southern Kaduna terrain, and consider the plausible population of each of them, which may lead us to a total population of about three million, or even over three million.

“This means about one third of the current population of Kaduna State’s about 10 million was displaced over those years; to me, this is not credible,” he explained.

“I am a prominent indigene of Southern Kaduna; most of us are more inclined to seeing the number of the affected villages in a few hundreds, if we can even confidently say that, and this is verifiable by everyone concerned with the situation of the region.

“And even in the event of attacks, we cannot say they were completely banished; majority of them are deserted only for sometime; then many of their occupants trickle back home from wherever they have fled to after the attacks, when they are sure that the insecurity has sufficiently abated. This, also, is verifiable.”

“Many villages are now deserted because most of the houses have been razed down in attacks and reprisals,” a dependable Kaduna humanitarian crisis manager said, adding, “their thousands of occupants have fled, perhaps, forever, to found new settlements around urban centres like Kaduna and Kafanchan, and even Abuja.”

The inability of government or any authority in humanitarian crisis management to open formal Internally Displaced Persons camps orchestrated the instant flight of survivors of violent attacks to the safer regions.

“The persistent situation of attacks, reprisals and counter-reprisals has adversely affected farming in this region, because peace and security of the outskirts are the fundamental requirements of every farmer venturing to the fields,” Alhaji Ahmadu said.

“This year, most farmers could not even venture to the farms for fear of attacks, and kidnappers,” he lamented.

Ayyuba Ibrahim (Garanti), a Kafanchan ginger farmer, estimates that agricultural outputs have dipped by about 35 per cent in three years.

“Over three years ago, when the attacks and reprisals were less, I used to harvest about 300 bags of ginger,” the former Publicity Secretary of an association of ginger farmers lamented, adding that he could only harvest about 150 bags in 2019 because he was too afraid to go to his farm.

Garanti said he had lost hope in harvesting any substantial quantity this year. “I have resigned to my fate of sharing my harvest with weeds, because I could not venture to the farms to cultivate them well,” he told HumAngle.

He added that violent conflicts had deeply impoverished most farmers and agribusinesses in the region.

“Clashes erupt mostly during the cropping and harvest seasons, scaring away farmers from the field,” Garanti noted, adding, “this has deprived Southern Kaduna of its major quantum of tonnage of farm produce.”

Alhaji Saidu Abdu, the Sarkin Noma (Chief Farmer) of Lere Local Government Area, which borders Zangon-Kataf, also blamed the violent conflicts for poor farming yields.

The prominent farmer did not want to estimate how much has been lost in produce over the years but described it as “frighteningly monumental”.

He, however, observed that this year’s harvest season witnessed a shortfall of about 20,000 metric tonnes of maize alone compared to 2019, when products flooded the markets, especially in Saminaka, where farmers sold their stock.

It is feared that the longer the conflicts persist, the more they will drastically reduce the quantity of harvests, further sink the population into hunger and impoverishment, and continue to push people from rural to urban areas.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter