How Mobile Financial Service Providers Rob Borno IDPs Of Much-Needed Aid

When international NGOs give cash support to displaced people, it is often paid through e-vouchers that are linked to special debit cards. But because of the activities of shady middlemen, not all these donations get to the intended beneficiaries.

The lack of effective oversight from aid organisations in Northeast Nigeria has made it easy for poor internally displaced persons (IDPs) to be robbed of their entitlements. This gap has especially been exploited by Point of Sale (POS) machine operators hired to disburse monthly feeding allowances.

Hunger and lack of access to livelihood are some of the major problems afflicting IDPs in the northeastern state of Borno, which has been ravaged by violent extremism for over a decade. And while the government and non-governmental organisations are often blamed for not investing enough to cater to the needs of displaced people, there is also the problem of ensuring allocated funding gets to the intended beneficiaries.

IDPs at the Gubio Camp in Maiduguri, Borno state capital, recently raised alarm on POS operators, engaged by the World Food Programme (WFP) to dispense aid to them under the cash assistance programme, had been shortchanging them, a development that worsens hunger alongside other difficulties among the displaced people.

While POS transactions have traditionally been used by businesses to receive payments for goods and services as an alternative to cash, the machines are now used by millions of people across Nigeria to withdraw money from their bank accounts. Rather than visit banks or Automated Teller Machines (ATMs), many prefer to patronise POS operators who charge higher transaction fees but are often closer and more available, especially in rural areas. While the size of transactions conducted using the POS terminals was just ₦46.9 billion in 2012 when they were introduced, last year they stood at ₦6.4 trillion according to information from the Nigeria Interbank Settlement System (NIBSS).

The WFP has confirmed that it carried out a six months cash assistance programme in the Gubio camp that lasted between June and Nov. 2021. Gubio camp is one of the displacement facilities in Maiduguri, whose residents are facing severe hunger and deprivation due to the suspension of humanitarian assistance following instructions from the state government.

To ensure the cash assistance programme was hitch-free, WFP engaged the services of Access Bank to disburse the money through POS operators. The United Nations agency has often engaged telecommunications companies such as Airtel and financial service providers to implement its cash-based transfers. By doing so, the WFP, like many other NGOs, does not directly handle the disbursement of money to the recipients.

HumAngle understands that for the enlisted IDPs to benefit from the e-voucher cash disbursement, each head of a household was issued a ‘wallet account’ linked to a debit card.

Every month, the wallet was credited with the sum of ₦54,000 per household of six persons, which the IDPs withdrew through the accredited POS operators. The operators typically took ₦1,000 as a service charge, while the household of six IDPs went home with a balance of ₦53,000.

But the disbursement programme went on with a lot of irregularities preventing it from achieving its poverty alleviation objective.

Our reporter gathered that while some of the IDPs confirmed receiving their cash through the POS operators, many others claimed they either did not receive the money at all or that all they got were a few months’ disbursements.

“That wouldn’t have been a problem but we later came to find out that there had been debit records in the accounts of most of the IDPs whom the POS operators claim their money had failed to drop on the ATM cards,” said Idris Musa, a spokesman of the IDPs in Gubio Camp.

The IDPs wondered why an electronic system of payment that captured their biometric details at the same time could be experiencing such discrepancies when it comes to the disbursement of the money.

HumAngle gathered from the IDPs and some bank officials that for each of the ATM cards issued to the beneficiaries, a unique PIN was provided, but this PIN is not accessible to the IDP. Only the bank and the cash agents have access to it. This means there was no way for the IDPs to independently verify whether their money had dropped in their wallet.

“We don’t even have any idea whether the money had hit our accounts or not – all we did was to work with whatever the POS people told us,” Idris, a 52 years old fisherman from Baga said.

The crooked deals

HumAngle learnt from many of the affected IDPs that some of them were cajoled by POS operators to surrender their cards in exchange for quick cash.

“A particular agent sent out boys to the IDP camp with a million naira to help him ‘buy’ 100 e-voucher cards with an agreement that a certain agree amount would be deducted monthly in exchange for quicker access to cash,” said Modu Ala, an IDP from Gwoza.

HumAngle understands that the cash for food programme, designed to last for six months, provides ₦9,000 to each person as a monthly allowance. But the disbursement is done based on the household. The sum of ₦9,000 is multiplied by the number of persons in a household.

For each person in a household, the POS vendor takes ₦1,500 and ₦250 as service charges.

“What they do is that if, for example, a household of two persons is entitled to get N18,000, the POS merchant would deduct ₦3,500 from the account and then give the IDP ₦14,500. If a household of four is supposed to be paid ₦36,000, the POS Merchant gives the IDPs ₦29,000 and holds onto ₦7,000,” Modu said.

In a month, a merchant who has, for example, 100 households of four persons, from whom he takes ₦7,000 under his illicit arrangement, goes home with about ₦700,000. And if that goes on for six months, the thieving vendor nets up to ₦4.2 million.

But that was not even the worst-case scenario for the swindled IDPs. Many of the IDPs claimed they did not get the balance of their monies even after the illegal deductions had been made.

According to Idris, the POS vendors claimed the accounts of the concerned IDPs were not credited for different months, but this was later discovered to be false.

Idris said though he was lucky to have received a large amount of his money, hundreds of other IDPs still have either not been paid or did not get a dime till the programme was suspended last year.

“So we were advised by some camp officials to go to the bank and demand bank statements relating to each of our wallet accounts. But when we got there, the official told us we had no right to ask for a statement of account because what we had was a wallet account.”

Those conversant with how such accounts operate insisted that the official was not being honest and that every account issued to a beneficiary has its transaction history. Hearing this, the IDPs then approached a court for redress.

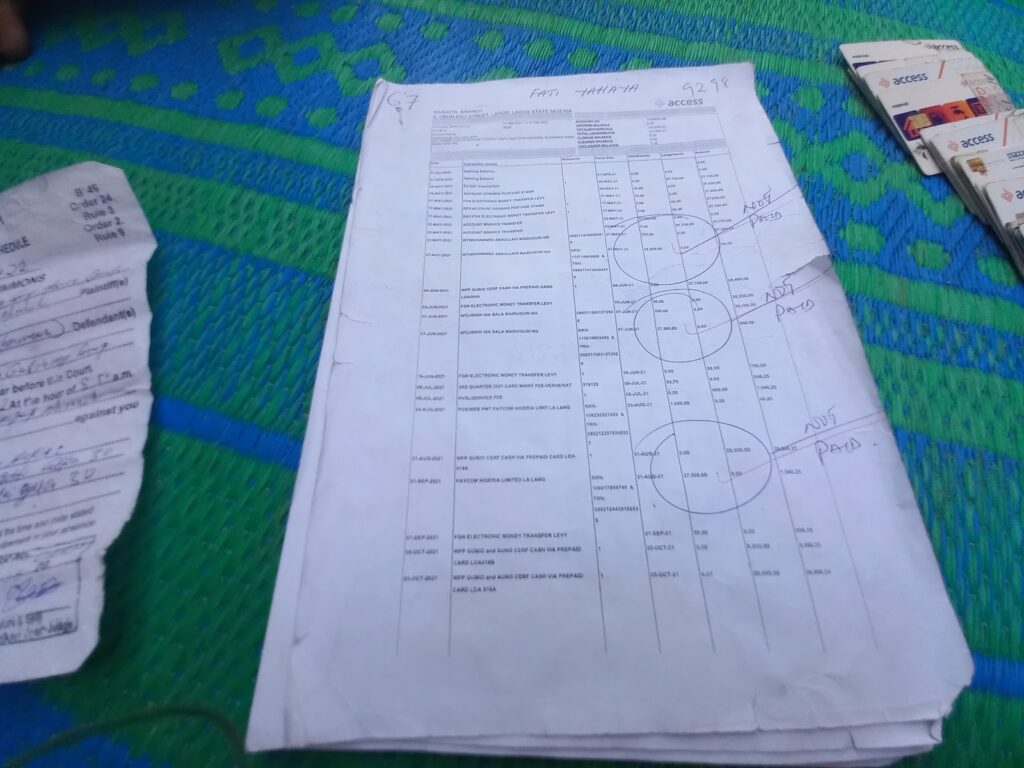

They secured a court order to compel Access Bank to provide the statements of accounts for every affected person who asked. The WFP had also recently confirmed this to journalists.

“When we secured the court order, we were able to get the bank statement for 202 complainants and, to our surprise, most of the statements indicated that the accounts had been credited for every month, contradicting the POS operators’ claims,” Idris said.

Despite securing evidence that their money may have been diverted, neither the POS operators nor the banks could explain what happened. “We reported the matter to the police in the camp; we also met with the area commander but no help came our way on how to get our money,” Idris lamented.

The IDPs felt their last hope was to report the matter to the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).

“Out of the over 1,300 IDPs affected, about 500 of them were those that did not have their monies paid to them. And our investigations revealed that most of the IDPs lost their monies to the POS operators and not due to technical glitches as claimed by the vendors.

“Initially the POS operators denied knowledge of what happened because they thought we would not be able to access the bank statements; but when we confronted them with the documents, they had no choice but to admit stealing our money,” he said.

HumAngle understands that the conduct of the POS operators was not an isolated incident, but rather reflects widespread fraud that prevails within IDP camps and around the humanitarian activities in Borno State.

“How, for God’s sake, could people be so heartless to descend so low as ripping vulnerable people like the IDPs of the peanuts they depend on to survive?” Barrister Jummai Mshelia of the National Human Rights Commission office in Maiduguri said.

Mshelia confirmed to HumAngle that the commission had received a formal complaint from the IDPs alleging theft by the POS operators.

“There is a lot of suspicion about the operations of the POS operators concerning the way they handled the disbursement of money meant for the feeding of the IDPs,” she said. “We have made some investigations and we have also visited the camp and even spoke with the camp manager who confirmed the claims of the IDPs.”

Mshelia said her commission invited the chairman and other officials of the POS operators who confessed that they had withdrawn and held onto the monies meant for the IDPs.

“When we confronted them with the bank statement, the POS operators agreed that they had about ₦600,000 meant for all the IDPs who raised complaints about their monies, but they would not be able to pay them all the money, that they would rather give them half and pay some of the remaining at a later date. Even when the IDPs agreed to that out of desperation, the operators still could not pay up.”

A security officer attached to the camp informed HumAngle that the operators decided to stop paying the IDPs “when the state governor came here to announce that the camp would soon be closed and the IDPs would be returned home.”

“That’s how they normally defraud them. The operators’ thinking was that as usual the governor’s pronouncement would be followed with immediate evacuation of the IDPs, but that hasn’t been the case — the IDPs are still here,” said the officer who asked not to be identified in this report.

WFP’s National Communication Officer, Dr Kelechi Onyemaobi, while responding to journalists’ inquiries on the matter, confirmed receiving such complaints from the IDPs in 2021.

He said the organisation had visited the camp to investigate the issues raised.

“WFP officials visited the Gubio Camp on Oct. 26, 2021, to investigate the matter and confirmed the veracity of the complaints by the IDP. And the WFP immediately intervened to assist the IDPs to get the statement of their accounts from the bank being used for the disbursement of their entitlements. The statement enabled them to verify whether their entitlements were paid or not.”

“Out of the 55 complaints received by WFP, 30 were found to be valid after verification. These were addressed and resolved,” he said, adding that the state was no longer working with the affected cash agents and that the programme ended last November.

How we were defrauded

Bakura Laminu said his three months’ cash support from WFP was stolen by POS vendors.

“I have confirmation that the three months cash support of ₦27,000 per month was credited to my wallet, but the POS people took it all.”

Umar Abba, an IDP from Bama, similarly said two months of cash support was not remitted to him. “I have eight persons in my household and the total pay for two months that the POS merchants have denied me is ₦108,000,” he said.

“They kept telling me that the account was not credited for the last two months but when the bank statements were issued, we found out that the account had been credited and the whole money for the two months had been withdrawn through their POS machine.

“I need my money because my family depends on it now; we have no food to eat.”

Musa Ismail from Doron Baga said cash agents had held onto his three months’ money and his card.

“We were starving and I needed money to buy food so I took my card to Ahmadu, the POS vendor, who gave me ₦5,000 and held on to the card from which he would withdraw his money and his usual commission. But he refused to give me back my card and my remaining money for two months, saying that it had not been credited. My son was later able to raise ₦5,000 to pay off the debt, but he still refused to surrender my card and the money.”

Like Umar’s, 65-year-old Ismail’s household was entitled to a monthly pay of ₦54,000 and is owed two months of allowance. The POS vendor, Ahmadu, was invited to the NHRC office where he claimed that he had the card but it got lost.

Lema Abdullahi, from Doron Baga, said the POS operator has held onto his ATM card and his two months’ pay.

“I had two wives and eight children, but one of my wives recently died of high blood pressure. The POS vendors had refused to hand over my money for two months amounting to ₦180,000.

The IDPs’ spokesperson, Idris, said the total amount owed by one particular POS vendor to 10 households who didn’t get their money for either two months or four months was about ₦1.4 million.

Asked why they settled for the 50 per cent refund offer, one of the IDPs, Lema, said the merchants had threatened that they could go ahead and sue if they did not agree.

“So we became afraid that we may even lose all the money if we dragged further, that was why we accepted the deal. But sadly, the POS vendors only turned up with a quarter of the money saying that was what they could afford at that moment,” Lema said.

“We have no strength to fight with them.”

One of the POS operators engaged for disbursement told HumAngle that “there had been a misunderstanding between our members and the IDPs” and that it was being resolved.

“It is true that some POS merchants had challenges in getting the money out on time, but I won’t say all of us are to blame. There are hundreds of IDPs involved, but it is just a few cases that we had problems with and [we] blamed the POS vendors concerned. I don’t have the details but I guess they have had some amicable agreement on paying the unpaid monies owed to the IDPs,” he said.

Expert senses fraud

A retired banker and monitoring and evaluation specialist, Stephen David, raised eyebrows at the manner the entire project was handled.

“A cash-based programme is usually guided by policy documents to ensure beneficiaries are not shortchanged and to forestall any form of abuse of power by staff or non-staff that are exercising powers on people affected by conflict,” he explained.

According to him, a key component of the CBT programme is ensuring that cash vendors are vetted and known for high integrity before they are engaged.

He faulted the WFP programme for allowing banks to issue ATM cards to beneficiaries while the PINs are withheld.

“The vendors are required to issue receipts of payment to beneficiaries and are not to have access to beneficiaries’ secure passcodes. More so, the finance unit and internal control monitor vendor payments while the Management of Information system reviews beneficiary wallets to ensure compliance is maintained in real-time.”

David assessed the bank statements obtained by the beneficiaries as “genuine documents detailing banking transactions done on the accounts or wallets of the beneficiaries”.

“It is sad that despite numerous complaints from the beneficiaries, it appears their cry was never addressed or was not registered at all. These beneficiaries who are seemingly vulnerable had to accept an unofficial part payment of their entitlement after a rigorous battle with the banks for their statement of wallets created,” he said.

“The WFP project, giving the complaints made by the beneficiaries, was short of minimum standards for a CBT programme and portrays a high propensity of an insider job which has not been refuted by the organisation.”

This report was produced in partnership with the MacArthur Foundation under the ‘Promoting Transparency in Insurgency-Related Funding in Northeast Nigeria’ Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter