How Children’s Dreams Are Crushed In Abuja’s Leper Community

The children find it hard to chase their dreams as school means more expenses for their parents who find it almost impossible to feed their families. But these children still have their dreams and hold on to them.

Three boys appeared with grass heaps on their heads and sickles in their grip. Two of them, Mudathir, 11, and Masirana, 12, are not lepers but their parents and grandparents are. So, they are stuck here at the Alheri leper community located on the Abuja-Kogi expressway inside Yangoji Village, Kwali Area Council in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja.

Dreamers

Mudathir, who is in his first year at a government-run secondary school near the colony, has big dreams of becoming a lawyer.

His companion, Masirana, on the other hand, desires to be a soldier when he grows up and longs to get out of the community. “But for now, I don’t have a choice,” he says.

Currently, the two boys’ typical day involves cutting grasses after school hours and selling to members of their community who own livestock but are unable to do the feeding labour because they are lepers.

The boys make between N150 and N200, depending on how much grass they are able to cut daily. With this amount, they are able to meet some of their personal needs without depending on their guardians who struggle financially.

The girls are also not let out of the grass cutting hustle, especially because there is little else they can do with their time.

The girls dream too

By the left side of the community is a yellow building with green roofs. It is the community’s primary school of eight classrooms, including a principal’s office and collapsed pit toilets.

After their primary education at the community school built during former President Goodluck Jonathan’s administration, some of the children do not continue with their education because their parents cannot afford the fees.

Basira, Zulaiha, and Hafsat are typical examples of some of those who have been denied access to education because of their parents’ health conditions.

“I was in school a few years back. I stopped in JSS three because I didn’t have the means to further my education,” Hafsat, 17, says as she fiddles with her hijab. “We don’t even have anything to eat because we don’t have money to buy food.”

Hafsat wants to be a medical doctor but everything seems to be kicking against that at the moment. “It is an impossible thing,” she adds. “I want to plead with the government to please look our way. We need to eat to survive and we also need to go to school to become what we want to become.”

To get by, Hafsat began hawking but had to stop after a while because “people don’t like buying from us because of our situation.” So, she is currently at home with nothing to do.

Fourteen-year-old Zulaihat’s peach colored hijab shone in the afternoon sun as she made her way to Islamiya – Arabic school. She tells HumAngle that she only attends Islamiya as her mother cannot afford to pay the fees for her conventional education.

“My mum is a leper. We came back here when my dad passed away. My Mum doesn’t get enough to feed us as she is a beggar, so after islamiya I go to the bush to get grass and sell so we can eat,” she explains with her head down.

When HumAngle asked Zulaihat what she would like to do in the future, she said: “I want to start saving money so I can go to school. I want to become a doctor in the future so I can help my people.”

Basirat did not fiddle and smile as much as Zulaihat did but their ambitions are similar despite their different family situations. Both of Basira’s parents are alive but with her father being a beggar, they cannot afford her education.

“I have graduated from primary school but I am yet to enroll in secondary school,” she says. “I am praying they get the money to take me because I want to further my education and even go to the University. I want to be a doctor and I want to take care of my family and the people around me.”

Basira tells HumAngle that she sells food at a nearby filling station but barely makes sales because people do not like to buy from her. Like the rest of the children who spoke to HumAngle, Basira does not have leprosy but remains trapped in the colony because of parents who suffer from the disease.

The list of children in the leper community who aspire to be something great in Nigerian society goes on. There is 12-year-old Mudasir who wants to be a lawyer, Murtalla who desires to become a doctor, and Usman who dreams of being an accountant.

Then there is Sanusi who visualises his adult self in a soldier’s uniform and Abbass whose amputated arm does not stop him from aspiring to be a policeman. The children of the Alheri leper colony continue to dream big despite their present reality.

‘We suffer neglect’

Dressed in a blue kaftan, Ali Isa, head of the Alheri leper community sat on a chair flanked by other men on wooden benches.

In 2020, HumAngle visited the community and the residents gave details about their plight. Sadly, nine months after, there is still no significant change to their situation.

Besides the addition of 20 housing units (courtesy of an NGO), and improved electricity, not much has changed for the people.

Members of the community point out that the lackadaisical attitude of the government towards them makes it seem as though the government put them out to dry by moving them out of Durumi, Abuja Municipal Area Council (AMAC) where they were formerly residing.

“I prefer Durumi to this place because we got more attention and donations there,” Mairo Ali, one of the women, says.

They were moved out of the area to prevent them from begging in the city centre, as well as protect them from road accidents that some of them were victims to.

A monthly stipend, which they got during former president Olusegun Obasanjo’s administration, had stopped coming since 2007 when the former FCT minister, Nasir El-Rufai’s tenure ended.

“During the Obasanjo administration, we were paid N4000 each and I was paid N600 as the village head, but the government stopped paying us after we were moved to our settlement.”

“We have been here for fourteen years and no administration has ever paid us any stipend until recently when the Buhari administration started the trader moni program in which we were enrolled.”

“They paid N10,000 once but we received the second payment about seven or six months later,” the community leader complains. Several men in the community add that the current FCT minister, Mohammed Musa Bello, has not shown them any kind of support. One of them told HumAngle that they are still short of housing units, despite the 20 extra added by an NGO named CSDP. “Some families have to make do by living in the kitchen of some housing units because the houses are not enough,” he explained.

We farm with our disabled hands

Even though they are unable to have a firm grip of farming implements, the lepers still cultivate their farmland regardless; an action which the American Leprosy Missions suggests, would put them in more danger.

Mycobacterium leprae, the bacteria which causes leprosy “attacks nerve endings and destroys the body’s ability to feel pain and injury.

“Without feeling pain, people injure themselves and the injuries can become infected, resulting in tissue loss. Fingers and toes become shortened and deformed as the cartilage is absorbed into the body.”

On top of having to farm with stubbed fingers, the community cannot afford needs such as fertiliser to make their plants grow properly.

“All the farm lands you see here are ours. We planted all the crops you’re seeing but we don’t have the money to afford fertiliser. Sometimes we go to Area One to work and earn some money to buy fertiliser because you cannot farm without fertiliser,” one of the men complained.

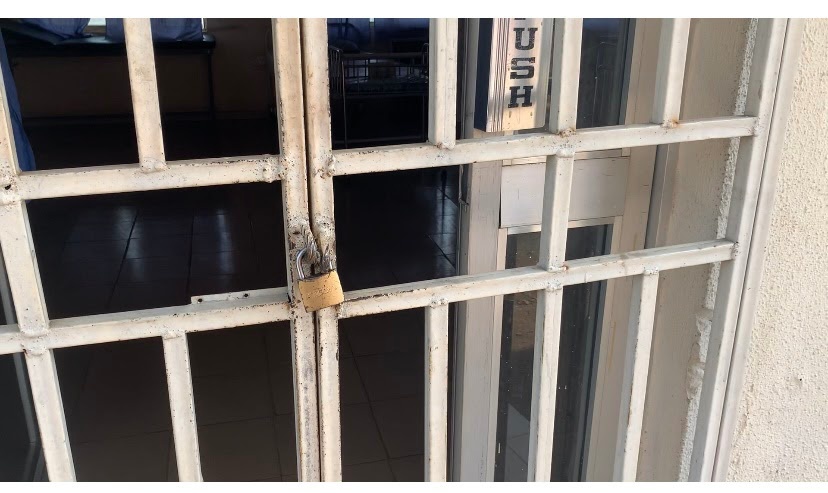

‘What we have here is a ghost clinic’

At the entrance of the clinic is an abandoned and weather beaten version of what used to be a white 1960s Peugeot 504. “This is the ambulance they gave us,” one of the men offers.

The clinic itself is under lock.

By a mango tree in the centre of the village, a petite elderly man narrated his ordeal: “My grandson has been sick for weeks now, he did not get medical attention because the clinic is not functioning. I had to raise money in order to take him to the one in Kwali because he was hurting so much.”

“When someone falls ill, we contribute money for the medication because not everyone can afford to pay for medication,” one of the women adds resignedly.

“There is a boy who is currently sick and has been in the hospital for almost two weeks without medication because his father can’t afford to pay for his medical bill,” another woman says.

In the event of a woman who is in labour, “we look for a car and take them to Kwali. The government has abandoned us here,” yet another woman, Hajara Salisu, chips in.

Muhammad Adamu Alkali, an elderly man whose feet and hands are without toes and fingers respectively, tells HumAngle that the nonfunctional state of the hospital is taking a toll on him. “The things we are lacking are much. Take for instance the hospital we have here. Right now I am sick but I can’t even go there because it is as good as useless.”

“Last night my daughter was sick but there was nothing they could do. I had to call someone to help me take her to a nearby chemist,” Alkali laments as he sits helplessly in front of his house.

HumAngle counted six hospital beds in the clinic, a number which may not do much in the event of a cholera outbreak which is common during the rainy season.

Behind the clinic is an abandoned building meant to be a pharmacy where a man displays leprosy educational posters.

Alheri community’s women

The women say they want their children to be educated and have jobs but they lack the means to support them. Mairo Ali, 57, is the community’s women leader. With her husband dead, she caters for her five boys alone, a feat she says is difficult.

Speaking on behalf of the women, she says: “We are suffering here. We don’t have food to eat and we cannot get a job because of our health condition. If we go out to beg on the street, they arrest us and demand a huge amount of money before we are released.”

Having barely enough to feed their families, the women dream of formal education for their children.

Mairo told HumAngle that they get donations from well meaning wealthy individuals, and they pray everyday for their children to become wealthy too so that they can relieve them of their sufferings.

“If they go to school and get educated, they will have jobs like you and be able to help us. But, unfortunately, we don’t have the funds to enroll them in schools so we are pleading to those wealthy individuals to help us,” she adds.

Cloth as sanitary pads

The cleaning and laundry jobs the women get is barely enough to cater for their children’s upkeep, talk less of buying them sanitary pads.

“We do not have the money to take care of ourselves as women. So during menstruation, we use pieces of cloth because we cannot afford sanitary pads,” one woman says.

“I have no means of getting money for anything. I feed on the little my parents provide. During my period, I use a rag. I usually get a piece of cloth, cut it into two, and then use it for the whole five to seven days,” a shy teenage girl tells HumAngle.

——————————————————————————————————–

This story was produced in partnership with Civic Media Lab.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter