How A Young IDP’s Encounter With Boko Haram Opens Up Old Wounds Of Atrocities

“Seeing relatives of insurgents who inflicted pain on my family inflames my trauma.”

The worst period of Aisha Abba’s life was when members of the terror group, Boko Haram, invaded her community and took many of them into captivity, seven years ago.

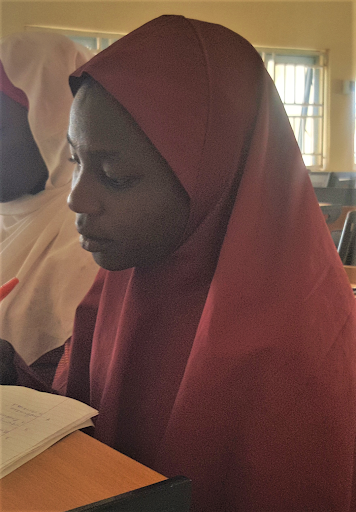

Now an internally displaced person (IDP) living in the host community of Maiduguri, the 21-year-old girl from Bama, Borno State, Northeast Nigeria, says she still finds it difficult to put the rough experiences behind her.

“Each time I see some persons whose faces make me recall my past experiences in Bama, I get angry and begin to cry,” she said.

The undergraduate of Borno State University said those who attacked Bama town about seven years ago and caused so much pain for her family are people she knows, “people that we once lived together with.” Though the insurgents themselves are either dead or still dwell in the bushes, the daily sight of some of their non-combatant families is incredibly traumatising for her.

Aisha was 13 years old and about to enrol into secondary school when the terrorists struck around 4 a.m., and seized Bama town on Sept. 2, 2014. She has since then witnessed several forms of trauma. She was not only forced by her abductors to witness gory scenes as a child but also lost close family members, including her brother and mother.

Aisha, who still recalls the bitter memories of the past seven years with much clarity, says, even if she wants to put the past behind her, certain individuals who have family relations with the insurgents keep refreshing her anguish.

Her case seems to question whether the strategy adopted by the Federal Government’s Operation Safe Corridor programme is the right one. The initiative, launched in 2016, seeks to reintegrate some repentant, pardoned, and deradicalised insurgents into society. Hundreds of them, who passed through a military-operated facility in Gombe State, have already been allowed to return to their communities or anywhere they feel safe to live as free citizens. Many of those who ventured back to Borno were vehemently rejected.

A senator from Borno state, Ali Ndume, went public with his criticism of the programme, arguing that it would rather aggravate the pain and anger of the victims.

“The government should know what to do about them but not reintroduce someone to you who has killed your parents or your relations. Not that he even apologised to you. He apologised to the government. His thinking was that the government has failed, and that is why they are being pampered,” he stated.

Though Aisha says she has no intention of fighting any repentant armed insurgent as she seeks solace in the Islamic teaching of forgiveness, she laments that this does not treat her trauma. The mere sight of people related to those who attacked her community still troubles her mind.

Memories of Bama attack

“I could not run fast, and the Boko Haram fighters rounded us up. They herded us into an empty compound near the deserted palace of the Shehu of Bama,” she recalled.

“Most of us girls and young women were held in captivity for over three months. Escaping from Bama, then, was a mission impossible for us because roads leading out of Bama were blocked by armed Boko Haram fighters who would drag us back to the town each time we attempted to flee to Konduga or Maiduguri. Those who were not lucky were shot at and thrown into the water under the bridge at the entrance of Bama.”

Aisha had been preparing to enrol into secondary school but the insurgents shut down all the schools and even prevented them from attending Quranic schools. Meanwhile, she was determined to make things difficult for the invaders as much as she could.

“I was a stubborn abductee for Boko Haram because I practically refused to heed to all their instructions. I refused to carry out the chores they assigned to me. I escaped several times but in each of the attempts, I would be arrested, flogged, and dragged to some empty house and locked up for the whole day without food,” she narrated.

“There were about 200 girls that were locked up in a big house in Bama. Many of the girls were, from time to time, dragged out and taken away for marriage to some commanders and fighters in some villages.”

The wedding process, she said, was “the most ridiculous.”

“After they had profiled the girls based on their beauty, skin colour, and body curves, they would mumble the holy salutation of the Prophet of Islam five times, and the girl was married — no dowry was paid because they’d say she had no Alwali (guardian or parent) around. But if the girl’s parents were known, they would take N5,000 to them and force them to receive it as their daughter’s bride price.”

Psychological torture

Disobeying the abductors’ instructions came at a price. Aisha and others like her were forced to witness horrible scenes like the flogging of aged people or slaughtering of anyone caught attempting to escape.

“They would drag out old persons, especially women and old men who disobeyed them, to an open place, and we were forced out to witness how they would be slaughtered like rams,” she recalled.

“They have separated many mothers from their underage children, including some months-old babies who were still being suckled. There was a woman whose baby was snatched from her chest while she was breastfeeding it. Most of the babies were taken to Gwoza, which was at that time declared the caliphate headquarters of Boko Haram.”

Aisha learnt that some women in Gwoza, wives of the insurgents, had been assigned to take care of the infants who were later taken to the terror group’s hideouts in Sambisa forest.

A parent’s suffering

While Aisha was held captive, her parents, who were restricted to their homes within Bama, were constantly harassed by the insurgents.

“My mother died because of the trauma she suffered due to the rumoured death of my senior brother whom a Boko Haram neighbour said he killed,” she said.

“One of the Boko Haram members, whose parents are our next-door neighbours, came to tell my mother during the occupation of Bama that he had killed her son, my brother. My mother fainted upon hearing that wicked news. She did not recover from the high blood pressure condition until she eventually died. And sadly, my brother had not died, as claimed. He survived an attempt to kill him.”

“So, each time I see the mother of that Boko Haram man that came to torment my mother, it would be as if I am seeing her son who wanted to kill my brother and later used the fake news of his death to take the life of my mother. Each time I recall my experience, I get angry and begin to cry.”

Aisha’s best friend and age-mate, Momi, was abducted during the occupation, and she has since not set eyes on her. She learnt Momi’s father is now down with a partial stroke due to the trauma of losing his daughter.

“I also cry each time I recall my experience with Boko Haram because they are the cause of my mother’s death. Left for me, I will never forgive Boko Haram for what they did to me and my family, but as Muslims, we are asked to forgive. It is so painful that those who turned against us as Boko Haram were people that we know and have lived together with in the same neighbourhood,” she said.

“My heart fills with anger each time I see their relatives in camps or the town. I always feel like this is the family of those who inflicted pain on us.”

She described this pain as unforgettable, trying as she might have to forgive those who tormented her, her family, and her friends. “They claim they are devotees to the worship of Allah, but their action is in sharp contrast to that of a devout Muslim.”

After three months of being in captivity, Aisha and some other girls escaped after several unsuccessful attempts.

“It was in the dead of night at about 2 a.m. when we bolted out. We made it to Konduga two hours later. There, some soldiers saw us and interrogated us. Upon hearing our stories, they took us to Maiduguri, where government officials took us to Yerwa Government Girls Secondary School camp where I lived for some time before my sister asked me to join her in her home in Maiduguri.”

Aisha got enrolled into secondary school with the support of her sister, who now acts as her guardian as they have lost their parents. “Due to the death of my mother in 2016, I almost lost any hope of getting an education until she assisted me to graduate from Yerwa Girls,” she said.

Passion for education

“I want to go to school and be more educated, and that is the reason I am not considering marriage for now,” Aisha told HumAngle.

“Marriage is good but I discovered that it was one of the major reasons our mothers did not go to school. My being at the camp exposed me to meeting many female humanitarian workers, and I discovered that none was illiterate. Even the local women that come to do advocacy on WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene) and other related health programmes at the camp have at least a diploma or NCE.”

She added that women like her mother could not work for the government or non-governmental organisations because they were not literates. She does not want to end up the same way.

“Though she gave me the best upbringing based on the little Islamic and Qur’anic knowledge she had, I believe I can make more impact on my children and society if I am educated. It is for the lack of education that most of our brothers and even some sisters are Boko Haram members today,” she said reflectively.

***

This report is part of a series of publications supported by the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) under HumAngle’s ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter