Hope Fades For Sokoto Farmers As Perennial Flooding Destroys Farmlands

Nigeria’s annual flooding crisis has left many farmers on the brink, destroying farmlands and sending billions of naira worth of investments down the drain.

The unusual roars of the cloudy sky over the village of Tsitse chiselled a warm smile on Salihu Yakubu’s face. For months, the land had grappled with shimmering heat that routinely climbed to 42 degrees Celsius. But that Sunday evening, the scent of rain in the air gave the sixty-five-year-old and farmers like him a sigh of relief. Soon, they could till their lands for the new planting season.

Salihu could already see rows of maize stalks and rice paddies bellowing in the breeze on his five hectares of land. By the time the first heavy drops began to fall, he would have prepared for a bountiful harvest and income for his family to survive the year.

However, torrential rain last month dampened his expectations. His rice field and other varieties of crops he had planted were buried underwater, and the flood destroyed 779 hectares of farmland in the Gada area of Northwestern Nigeria.

It was a little after 4 p.m. on the last Sunday of July. Salihu plodded through his flooded rice field, pointing to a submerged field of mostly dead crops once a vast expanse of green rice shoots and maize.

“I put all I had into the farm and had high hopes for this planting season,” Salihu started, his breath reeking of disappointment and resignation. The father of twenty-five had hoped to earn higher profits. He had expected to harvest about 150 bags of maize and 200 bags of rice.

“I planted two hectares of maize, two and a half hectares of rice, and the other half for peppers. The water has taken everything away from me.”

Salihu said he spent about ₦1.5 million ($940) cultivating the land. His family is one of the many subsistence farmers in Nigeria whose primary source of livelihood has been upended by the flood. This situation has worsened fear about the country’s ability to provide access to sufficiently safe and nutritious food. Climate change and conflict in the North have also exacerbated the nation’s food crisis.

The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organisation warned that an estimated 26.5 million people would face food insecurity this year. This indicates a sharp rise from the 18.6 million people recorded in last year’s last quarter.

“It’s devastating. I don’t even know what we become of me and my family for now. I’d probably get a loan and plant what’s remaining of the seeds to take care of my family. I can’t afford to put so much into farming at this moment,” Salihu said.

A perennial flooding problem

Nigeria is used to seasonal flooding. Authorities often blame unusually heavy rainfall and climate change. However, poor planning, ignored environmental guidelines, and inadequate infrastructure have also contributed.

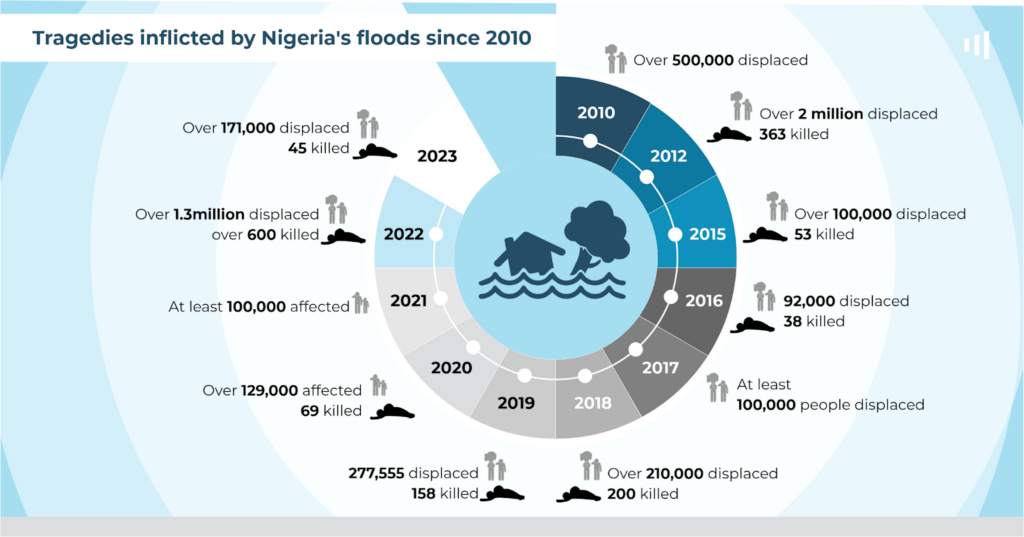

In 2010, Nigeria experienced a deadly flood after authorities opened the Challawa and Tiga Dams floodgates in Kano to prevent overflow. About 90,000 hectares of farmland were submerged, and an estimated ₦4.5 billion worth of food and livestock was destroyed. The country’s emergency management agency said over 500,000 Nigerians were displaced by floods that year.

Two years later, more than two million people were forced from their homes and 363 killed in what analysts said was the worst flood the country had seen in five decades. That same year, hundreds of thousands of acres of land were flooded when the rivers Niger and Benue overflowed following strong rains.

Later, in 2015, no fewer than 53 people lost their lives, and more than 100,000 were displaced in another flood that wrecked about 11 northern states. In 2016, 92,000 were displaced, and 38 died. More than 100,000 people fled their homes the following year in a major flooding that struck Benue state.

In 2018, about 200 people died after the main Niger and Benue rivers burst their banks. More than 210,000 people were rendered homeless, and about 150,000 hectares of farmlands were entirely buried underwater. In 2019, more than 100 local government areas in 33 states were affected by floods, displacing more than 200,000 people and hundreds of thousands of farmlands and livestock.

In 2020, no fewer than 129,000 persons were affected, while 68 persons were killed by flooding in different parts of the country, according to the National Emergency Management Agency. A similar flood in 2021 affected over 100,000 people across 79 villages in Adamawa, North East Nigeria.

“There are not really measures in place to handle those kinds of situations, whether to mitigate the impact or even respond when a disaster hits,” Mayokun Iyaomolere, an expert on environmental control and disaster management, says about the country’s preparedness.

“There is a whole lot that needs to be done. I know there are a lot of forecasts from NiMet [Nigerian Meteorological Agency] and other agencies about rainfalls and potential flooding in some areas. Still, this information needs to get to more people in local areas in their languages so they can prepare. We need this early warning system to get to people in all parts of the country.”

A cascading storm

Farmers were still trying to find their feet when the country recorded its worst-ever flood in over a decade in 2022. Nearly 700,000 hectares of land were destroyed, while at least 600 people lost their lives across 33 of Nigeria’s 36 states.

This happened on the backheel of the COVID-19-pandemic-driven food crisis and the subsequent Russian invasion of Ukraine, which disrupted the global supply of agricultural produce across Africa. This is further exacerbated by a raging conflict that has driven farmers off their farms.

Nigeria has faced food shortages and higher prices, with inflation reaching an all-time high of 33.95 per cent as of June 2024.

“The food crisis we’re facing today started with the pandemic, which disrupted farming globally. At the time, the market was just recovering. Then, there was the massive flooding and then the zero-cash policy that plunged the economy into crisis,” explained Ridwan Bello, co-founder of Vestance, an agri-food consulting company.

“Many farmers were unable to sell their produce, and billions of investments were lost. So, what we’ve today is a cascading effect of these factors. If we want to get out of this cauldron, we can’t afford to miss this year’s planting. Unfortunately, this year’s planting is gone.”

Like his neighbour Salihu, Mani Magaji had just started tending to his crops when the flood hit the area. His farm had been a tapestry of green-lush rice paddies, rows of fiery pepper, and maize. He had expected a bountiful harvest, expecting to yield about 140 bags of rice and more from the farm, enough to support his family and trade at the local market. In previous years, he had enjoyed such a harvest.

Sadly, all that promise lay buried under murky waters.

“The situation is saddening. I lost everything. Everything I’ve worked for, gone in an instant,” Magaji said. The flood didn’t only sweep away his crops but also his health. The 67-year-old spent two gruelling weeks in a hospital in Sokoto following the incident. “I’m just managing onions now. The rice paddies are all gone.”

Magaji looked at the waterlogged field with the side of his eyes before shaking his head dejectedly. “I’ve got a handful of seeds saved at home. It’s not much, but it’s all I have left,” he said, suggesting there’s little room for hope.

Jamilu Sanusi, chairman of All Farmers Association of Nigeria (AFAN) in the state, warned that the full impact of the recent flooding would likely be felt by the end of the year or early January. This is because farmers had yet to start harvesting when it happened.

“The food shortage that we’re experiencing now is only the impact of the many factors that reduced cultivation last year,” he said.

Of debts and uncertainty

The coming months will be tough. In the wake of last month’s devastating floods, hundreds of hectares of land remain fallow and uncultivated, as many farmers say they cannot afford all the seeds and inputs needed to replant their fields. Among those caught in the struggle is 45-year-old Isa Yari. He had borrowed ₦1.7 million to cultivate his three hectares of land. Now, he is worried about repaying his debts.

“I borrowed a lot of money. There is even an organisation that gave me fertilisers. They give us loans, and when we harvest, we pay them back.” He paused, looking out over his empty fields. “But now? There’s nothing to harvest, nothing to sell. Where will I find the money to repay this debt? I’ve been rendered helpless, unable to even take care of my own family. It’s so sad.”

He’s not alone. He’s not alone. Many local farmers told HumAngle they are caught between mounting debts and barren fields.

While some planned to replant the seedlings they had stored, the flood left Alhaji Buba with nothing to fall back on. At 73, he has weathered many seasons, but none quite like this. The seedlings and a few bags of fertiliser he kept in the house were also destroyed and washed away.

He led the way to what remains of his home. The water line on the walls tells a story of its own. “This small place where I stored the remaining seeds in the house was flooded too, washing away everything,” he narrated.

“I now have to look for money from friends to take care of my family and recover what’s left over from the farm and pay them back later. If not for this calamity, the harvest could have brought in about ₦7.75 million. Now, we’ve nothing but debts.”

There’s a long, lonely road ahead for the farmers. Jamilu said the state government has inaugurated a committee to assess the flood damage. But until their work is done, each passing day brings farmers like Isa closer to a reckoning they’re ill-prepared to face.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter