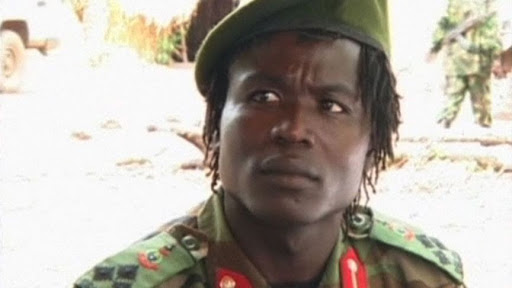

From Child Abductee To Rebel Commander: The Story Of Uganda’s Dominic Ongwen

Ongwen is currently facing criminal charges at the International Criminal Court for several crimes committed as a rebel, even though he was abducted and trained to become a killing machine.

Dominic Ongwen, a war criminal and former child abductee of the Lord Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda, was found guilty by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in February 2021, for crimes committed between July 2002 and Dec. 2005.

The circumstances surrounding Ongwen’s story calls for deep reflections on human rights in relation to child abductees groomed into becoming rebels, and their culpability in violence.

Ongwen, an ex-Uganda LRA rebel group’s commander, is the first LRA member to appear before the ICC. Having been convicted of 61 out of the 70 counts bothering on war crimes, murder, crimes against humanity, among other offences, before the ICC on Feb. 4, it makes sense to examine the peculiarities of his case.

Who is Dominic Ongwen?

Ongwen was born in 1975, Choorum village, Kilak County, Amuru district of Northern Uganda. He is the fourth son of Ronald Owiya and Alexy Acayo; his parents were school teachers.

His birth name was Dominic Okumu Savio, but his parents gave him Ongwen, a fake name, like many other families had done in order to prevent him from being linked to the rest of the family if he was ever abducted. By doing so, it would be practically impossible to track abductees families, and hence protect them from being killed or also abducted.

His abduction story

Ongwen was abducted on his way to school. The records are not in agreement as to the date of his abduction. Some reports say it took place when he was about nine or 10 years old because he was too weak to walk for long and had to be carried. Ongwen, however, in his testimony during his trial at the ICC, claimed he was abducted when he was 14 years old in 1988.

The uncontroversial fact about his abduction remains that he was a child at the time.

Shortly after his abduction, he tried to escape with three others and, when they failed, he was forced to skin alive one of the other abductees as a warning. This was disclosed by a psychiatrist during his war crimes trial at the ICC in The Hague.

Ongwen’s parents were found dead after the rebels returned to the village.

He was made to undergo a series of rituals as a child, including watching people get killed and maimed. He was subsequently tortured as part of the initiation processes to become a soldier.

From child soldier to rebel commander

Ongwen was trained as a killer and was forced into accepting his role as a child soldier. To stay alive, he had to obey rules, and submit to the dictates of his commander; Vincent Otti, as a child, and Joseph Kony, who led the LRA as an adult-ranked soldier.

He rose to become a commander of the Sinia Brigade, one of LRA’s four brigades, and led many attacks against civilian populations, and displaced people. During these attacks, there were cases of murder, pillaging, rape (causing forced pregnancy), and other war crimes.

One attack that stood out was the one at Lukodi IDP camp in Uganda’s Gulu district on May 20, 2004. His grave crimes against humanity during the incident formed the bulk of his charges at the ICC.

“Civilians were shot, burned and beaten to death. Children were thrown into burning houses, some were put in a polythene bag and beaten to death,” the judge, Bertram Schmitt, said while reading his verdict.

Dominic also became the first in legal history to be tried for the offence of forced pregnancy against seven women.

First abductee to be tried

Dominic Ongwen’s story is unique for the very reason that he is the first former abductee ever tried as a perpetrator before the International Criminal Court.

He was said to have surrendered before his arrest in 2005. He wasn’t captured.

During one of the times he received visitors while in detention, he asked for a rosary, a hymn book and a prayer book. In a video recording with journalists, he claimed that he had surrendered because he had come to realise that he was “wasting his time in the bush” as “the LRA has no future”. He also urged other insurgents to embrace civilian lives.

Ayot, one of his wives, testified to the ICC that Ongwen, along with two other commanders and herself, had plotted to escape, but their plan was discovered and Ongwen was demoted, disarmed and imprisoned for more than two weeks.

“The chamber is aware that he suffered much,” Schmitt said. “However this case is about crimes committed by Dominic Ongwen as a responsible adult and a commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army.”

The judge added: “His guilt has been established beyond any reasonable doubt.”

However, other commentators consider that the ICC indictments directly contradict the Ugandan Parliament’s blanket amnesty. This is because some LRA commanders had been given amnesty and received back home.

The sentence of Ongwen’s conviction is to be delivered on a later unspecified date. However, Krispus Ayena Odongo, Ongwen’s defence lawyer has disclosed intention to appeal against the ICC verdict, on grounds of Ongwen’s mental disorder.

LRA had been forced out of Uganda by the army in 2005, but still exists in the South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo and Central African Republic; either of which is believed to be their headquarters.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter