From Captivity to Uncertainty: A Young Nigerian’s Quest to Rebuild After Abduction

Umaru managed to escape from captivity after being abducted by a terror group. More than two years later, he is still struggling to piece back his life.

When Mukhtar Umaru trudged barefoot through dirt and thorns to escape from his abductors in Zamfara, North West Nigeria, about two years ago, one thought burned fiercely in his mind: a second shot at life. Someplace safe, he could live, away from the raging violence that has engulfed his village. While he indeed got his freedom, it was not without a price — a cost he’s still trying hard to pay.

Before his abduction, Umaru’s life goal of bagging a diploma in physical and health education was about to slip off his hands after the management of the Habibu Aliyu Yandoto College of Advanced Studies (HAYCAS) Tsafe ordered that students who had not completed full payment of their fees would not be allowed to take the final semester examination.

Umaru was, at the time, one of those who had not paid their outstanding fee. He was in a dire state, sorting his pregnant wife’s hospital bills. He told HumAngle that his wife was eight months gone at the time, and his farmland had lay fallow due to the increasing number of abductions by armed groups in the region. There was just one thing he could do to earn a living: get a job as a farmhand in Gandu near Daki Takwas village in Gummi, Zamfara state.

One day in mid-October 2022, Umaru left his home very early to make money for his school fees payment. Hoping to make an impression on his first day of work, he got to the Maize farm in Dajin Dankaraye, about 7km away from the town of Daki Takwas, very early in the morning. He had barely ploughed through the land when some noise and reverberating gunfires swirled around the farm. Six men brandishing their rifles emerged from their hideout to kidnap Umaru and eleven other labourers on the farm.

They were matched towards Gora, a village close to the Kawaye Forest in the Anka area of the state, where they had a guinea corn meal ordered by the gang leader before proceeding to Gando Forest in the Bukuyyum area of the northwestern state. When they got to Ruwan-kura village in the same local district, the armed gang, who were obviously also worn out, met with another terror group and sold them to the new group for just ₦500,000.

That trade-off presented an opportunity for Umaru to bond with a member of the new group, setting the wheel for his escape in motion. The new group ordered him to ride one of the motorcycles to Kawaye with one of the terrorists since he was familiar with the route.

Along the way, Umaru started conversing with one of the abductors matched with him. “The terrorist was surprised that I didn’t hate him. He gave me two sticks of cigarettes to smoke. I took it and smoked just to get his trust and effect my escape plan,” Umaru told HumAngle.

When they arrived at the group’s camp knee-deep inside the Kawaye forest, he familiarised himself more with the gang and even signified to join them despite being forced to sit under a tree and chained together. The more he experienced inhumane treatment daily, the more he developed the courage to escape.

On Oct. 28, he knew his chance to escape had come. Umaru shared his plan with a few fellow abductees he trusted, but they dismissed it as impossible. Later in the day, there was only a guard watching over them as others had strolled off to smoke marijuana. The lone guard, intoxicated and sleepy, eventually dozed off, his two guns lying carelessly by his side.

Umaru carefully freed himself from the tether. Though he tried to free others, they were tightly chained together, and he wouldn’t risk waking up the guard. He took an abductor’s shirt perched on a nearby tree and picked one of his guns as he stealthily walked away, praying his first step toward freedom wouldn’t be his last.

When he was sure he was out of harm’s way, Umaru abandoned the gun and removed the shirt before taking to his heels. His freedom was finally secured. However, his future still hangs by a thread.

Life after the escape

Everything about Umaru changed with the abduction. His dream of earning a diploma remains out of reach, now reduced to little more than a pipe dream. Though he is free, his daily existence is steeped in hopelessness and misery.

Following his escape, the management of HAYCAS allowed him to sit his final examinations on the condition that he would pay his fees later — a promise he has been unable to fulfil, despite assurances from a federal lawmaker representing his constituency. As of this report, Umaru has yet to obtain his ‘notification of result’ due to an outstanding balance of ₦37,000, which has remained unpaid since 2022.

The ‘notification of result’ is an official document issued by an institution to inform a candidate of their performance after the academic year. It serves as official proof of a candidate’s performance and can be used for various purposes, including employment opportunities.

“My random life is just going undesired, though people jubilated quite a lot when they heard about the risky tricks of how I escaped and arrived home,” Umaru said. But that is not all for the twenty-three-year-old. Providing basic needs for his small family has proven to be a nightmare, especially since the prices of commodities went off the roof following the sudden announcement of the removal of subsidy on petrol in May 2023.

Many families are still grappling with the ripple effects of the decision as the country battles its worst economic crisis in decades. And for Umaru and his family, it’s particularly devastating — a situation that has since forced him to return to work as a labourer despite his previous brutal experience.

“We’re living the life of a bird,” he said. “We eat whatever we see. And on days we don’t, the family spends the day on empty stomachs. The high cost of living made it difficult for us to even afford basic things.” Umaru added that what makes the situation different from when he was held captive is simply freedom.

“Although we now have freedom of movement, the hunger is still there — the same situation we lived in back at the den. The present relief is not far different from what it was during my captivity in terms of starvation,” he recalled.

A scar too deep to forget

Umaru still cowers in fear, unable to shake off the bitter memories even after two years. Seeing security forces with their guns triggers flashes of the terrible nights he spent in captivity. He still remembers the old guard that almost broke his ankle as he chained and forced him and other abductees to sit on the ground and tied to a tree like animals.

The rave of sporadic gunfires the terrorists used to instill fear in their captives left an indelible mark on him. Even now, Umaru said, the faintest sounds make him shudder, clinging to him like a shadow that refuses to fade. Meanwhile, there’s no provision for psychosocial support for victims of the conflict in the region, especially those who have spent longer periods with their abductors or witness the killings of their loved ones in cold blood.

The decade-long conflict has spawned a humanitarian crisis and killed more than 20,000 and displaced many from their homes, leading frontline humanitarian groups to describe the situation in the region as catastrophic. The region is still missing out in global humanitarian plans and support.

After his escape, life continues for Umaru, even though fragmented and shattered, just like many other abductees in the region. This is even more important as many abductees like Umaru told HumAngle that the terrorists often attempt to brainwash their victims. Umaru remembered one vividly, “I remembered one of the terrorists telling one of us (kidnapped victim) to find his way back to the camp after his release so that he can join the camp operations,” he told HumAngle.

“Terrorist preached to us that ‘now that you are here as our abductees. We demand ransom in millions for your freedom. Your parents and loved ones will sell farms, plots of land and other important valuables to make up the balance for our payment. What do you think would remain for you upon returning home?’” Umar recalled.

True to the terrorists, Umaru has found tracing back his life quite a hard nut to crack and his current mental state doesn’t help either. One moment, he wants to join the local vigilantes to root out the men who derail his life. Next, he’s thinking about providing for his family and shielding them from the violence that’s crippled their village.

When does this end?

The conflict in the region has upended many livelihoods. Hundreds of thousands of displaced residents are still trudging hard to find their feet. Umaru is yet to get his life together and he still works as a farmhand, braving the fear of being abducted again.

On days he’s free, he visits the Islamic school in his town to teach young pupils and talk about his bitter experience while in captivity. He said talking about it frees him from the clutches of the past.

“I now enjoy this because the parents of the children I teach at the Islamic school often visit me at home when they hear about my abduction and escape. They provide me with grain as almsgiving and Zakkat endowment. Most of them I don’t even know personally, but their children share many stories about me. This is how I’ve managed to survive for two years,” Umar told HumAngle.

However, he’s still determined to raise money for his result. He believes it would open doors of opportunity for him. The fee which was ₦37,000 before is now ₦67,500. “My hopes and prayers for the future are first to get the money, pay for the final registration fee and collect my results notification. If I can have my results, I have high hopes for success in the future, so it will not be a bleak one anymore,” he prayed.

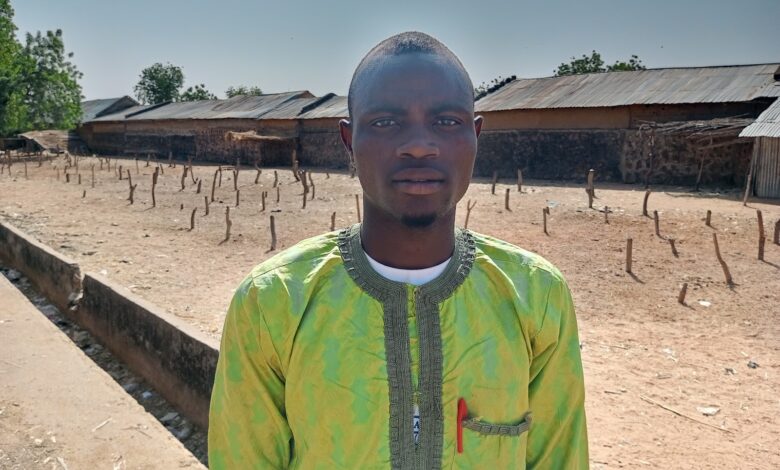

Mukhtar Umaru, a victim of kidnapping by a terror group in Zamfara, escaped captivity two years ago, but his life remains profoundly affected.

Originally a student at Habibu Aliyu Yandoto College, Umaru had to find work as a farmhand to pay for his diploma, only to be abducted again along with other laborers. After a risky escape, he faces the challenge of rebuilding his life amidst economic hardships and without psychological support, while struggling to pay outstanding school fees for his diploma.

In his bid to provide for his family, Umaru revisits his traumatic past by sharing his kidnapping experience in an Islamic school, receiving grain donations in return. The regional conflict and economic crises exacerbate his financial woes, as rising costs have increased his overdue educational fees from ₦37,000 to ₦67,500.

Despite the immense challenges, Umaru remains hopeful for future opportunities, determined to secure the results from his educational efforts.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter