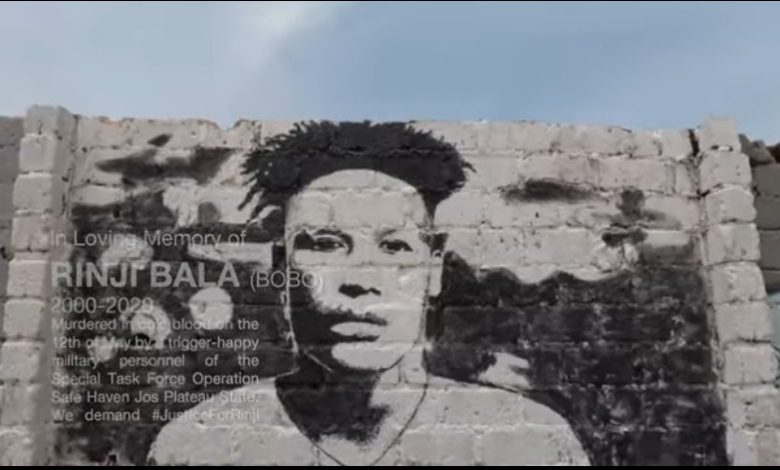

Five Years After He Killed a UNIJOS Student, Nigerian Police Officer Faces Death Sentence

Police officer Ruya Auta is sentenced to death for the killing of 20-year-old University of Jos student Rinji Bala during the COVID-19 lockdown in May 2020, in Jos, North Central Nigeria.

Ruya Auta, the Nigerian police officer who shot and killed 20-year-old Rinji Bala on May 13, 2020, has been sentenced to death by hanging or lethal injection. The sentence was delivered at a High Court in Jos, Plateau State, in North Central Nigeria, on Monday, Dec. 8.

Ruya was attached to Operation Safe Haven (now known as ‘Operation Ensuring Peace’), a Nigerian military joint task force established to quell violence in Plateau and neighbouring states.

“It has been five years of efforts and tenacity to bring justice to the deceased, the family, and even the government,” Garba Pwul, a Senior Advocate of Nigeria who represented the Plateau State Government in the extrajudicial killing case against Ruya, said afterwards. “It is a capital offence, so we had to follow the case carefully. Today, we have seen justice served.”

For those closest to Rinji, however, the ruling offered less a sense of victory and more a reopening of old wounds, a reminder of a night they never really escaped.

Emmanuel Gyang was there the moment Ruya pulled the trigger. He remembers the officer threatening to shoot him as well if he dared reach out to help his childhood friend. He and Rinji had grown up together in Hwolshe, a close-knit neighbourhood in the Jos metropolis, sharing games, long evening walks, and the small comforts of boyhood friendship.

“Since that day, there has been no peace,” Emmanuel said quietly. “The rest of the world forgot and moved on, but we’ve stayed with that day. I did not move past it, and I still haven’t.”

He sat in court on Monday as the sentence was read. “It was even while the judge was reading the judgment that I could process some of the moments,” he said. “He would say certain things, and it would dawn on me again that I was there.”

For years, Emmanuel avoided recounting the traumatic events leading to his friend’s death. He first spoke to HumAngle eight days after the killing, and when we spoke again on Wednesday night, he made an effort to revisit those memories.

“I guess it is time for us to heal,” he said.

Rinji was killed at a time when Nigerians were increasingly vocal about police brutality, which would later culminate in the 2020 #EndSARS nationwide protests. His killing became one of numerous cases cited by activists as evidence of systemic abuse and a lack of accountability within the country’s security agencies.

Rewind: May 13, 2020

Five years earlier, on a Wednesday evening around 6:30 p.m., Rinji had been out with five friends, including Emmanuel. After long hours indoors due to the nationwide COVID-19 lockdown, they had stepped out for a simple stroll around their community. Barely 300 metres from home, they crossed a pedestrian bridge above a major highway near the Plateau State Polytechnic campus in Jos, when shouts erupted from a nearby street—“Barawo! (Thief!)”.

Confusion seized the group. Emmanuel’s phone slipped from his hand, and when he stooped to pick it up, Rinji stopped to help him. The others ran. Within seconds, a mob caught up with them. “We were profiled, and we couldn’t even explain ourselves,” Emmanuel recalled. “It was all too fast. They wanted to lynch us until the soldiers came.”

The military officers intervened, interrogated them, and listened to their attempts to prove innocence. “We all said the same thing—that we went out for a stroll. Even the mob agreed they didn’t see us with arms or catch us robbing,” he said. The panic had stemmed from a recent spate of robberies in the area.

The young men believed they were safe when the officers intervened. Instead, the soldiers—stationed at a gated compound on 18th Street near Hwolshe—called in “the authorities”. More officers arrived. The boys were handcuffed and ordered to climb into a truck.

Neither Rinji nor Emmanuel had ever been inside a police cell. “Sitting at the back of the truck, it didn’t feel real,” he recounted. He said those words again. “We are not cultists or criminals to be walking around and watching our backs; it was just a stroll.”

A night of torture and death

They were driven about 10 kilometres to an Operation Safe Haven Sector 1 base at the New Jos Stadium on Zaria Road. The moment they climbed down, chaos descended.

“Immediately we got down, they started beating us, turn by turn—about ten of them,” Emmanuel recalled. Boots, machetes, big sticks, belts—anything within reach became a weapon. Water was poured on their raw skin to intensify the agony. Orders of “issue them” and “cease fire” rang out under the gaze of a senior officer.

“I was numb. It was humiliating,” he said. Up to that point, he could not think clearly or feel anything fully. Pain blurred into fear.

After frog jumps and more punishments, the boys were told to gather their belongings and run out of the base. On an ordinary day, it would take five minutes to reach the gate. That night, bruised, bleeding, and limping, it felt impossible.

Rinji reached the gate first. Emmanuel, struggling behind, was still some distance away when the gunshot cracked the night open. It was around 8:35 p.m.

Sergeant Ruya Auta, the officer manning the gate, had aimed, fired, and sent Rinji collapsing into a pool of blood. “I wanted to run to him,” Emmanuel said, “but the officer pointed his gun at me and said he would shoot me too.” In that moment, he feared nothing—not even death. His friend was dying before his eyes.

Seconds later, instinct overpowered terror. He ran. A stranger took him in for safety around the nearby Farin Gada area. “I couldn’t stand, I couldn’t sit, I couldn’t lie down. I was confused,” he said.

There, in that room, he called home. Peter Bala, Rinji’s father, had also heard his son was arrested, so he quickly rushed down to the base. He eventually located the young men at their hiding place after he got directions from Emmanuel’s mother.

It was when he met them that they told him that Rinji had been shot at the base.

Peter had walked past the corpse when he went to the base earlier to search, but he didn’t know it was his son.

The bullet pierced Rinji’s buttocks and ruptured his genitals, according to reports from the Plateau State Specialist Hospital. As he lay bleeding on the ground that night, with Emmanuel standing nearby, the senior officer who had supervised their torture drove past without offering any assistance.

“He was always such a lively person, full of life,” Emmanuel said of his friend.

Rinji was a third-year student of History and International Relations at the University of Jos and would have completed his studies in 2022 or 2023. He would likely have concluded the compulsory one-year National Youth Service Corps as well. His family remembers him as a “very gentle and cool-headed boy”. He was the lastborn and the only son among three children. He dreamed of becoming a diplomat and also hoped to establish his own fashion line. Rinji loved dancing.

‘Not to be forgotten’

On Monday afternoon, when the judgment was handed down in Jos, Peter Bala held Emmanuel’s hand. “He didn’t say much,” Emmanuel recalled. “One thing he said was that he doesn’t celebrate the death sentence, but there have to be consequences for every action, and some sort of deterrence.”

Peter never missed a day of court proceedings—not even those when the judge, or Ruya, or Ruya’s lawyer failed to appear.

Ruya’s defence had always been that the shooting was a mistake. In a May 2020 statement, the Operation Safe Haven claimed that Ruya, who was on sentry duty, “mistook them [the young men] for escaping suspects. Thus opened fire on them, which led to the death…”

Yet, according to Emmanuel, Ruya never showed remorse throughout the proceedings.

“I have seen him more than twenty times since that night—from the court, to the anti-police brutality tribunal. Sometimes he tries to play mind games with me. He calls my name and smiles,” Emmanuel said. “He is cold and arrogant.”

On the night of the shooting, he added, “He acted like a hunter chasing game. It wasn’t a mistake. Seeing him over and over has even worsened my emotions.”

As the call with Emmanuel drew to a close, he paused, then said quietly, “We do not want Rinji to be forgotten. Also, while we uphold his memory, hopefully, people who peddled all kinds of false stories about this incident will allow us to heal.”

Ruya Auta, a Nigerian police officer, was sentenced to death for the extrajudicial killing of 20-year-old student Rinji Bala on May 13, 2020. The court ruling revives the pain for those close to Rinji, who became a symbol of police brutality aligned with the 2020 #EndSARS protests.

The incident occurred during a COVID-19 lockdown when Bala and friends were falsely accused of robbery and tortured by the military. Bala was shot dead by Auta as they attempted to leave the military base. This case highlights systemic abuse and lack of accountability within Nigerian security agencies.

Rinji was remembered as a vibrant young man with ambitions in diplomacy and fashion. His friend, Emmanuel Gyang, who witnessed the traumatic event, emphasizes the need for healing and to ensure Rinji's memory endures despite misleading narratives.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter