Fighting The Education Boycott Imposed On English-Speaking Cameroonian Children

Oben Epey is one of seven children his parents took away from Anglophone Cameroon to Douala in order to be able to give their children an education Anglophone separatists are denying them in English-speaking Cameroon.

Ten-year-old Oben Epey has been out of school for the past five years. At his age, he has only had two years of schooling. He and his family escaped from the restive Southwest Region of Cameroon where Anglophone separatists have been visiting havoc on schools in a Boko Haram-type prohibition of schools.

Oben Epey is one of seven children his parents took away from Anglophone Cameroon to Douala in order to be able to give their children an education Anglophone separatists are denying them in English-speaking Cameroon.

His case is not unique as he is one of about 700,000 English-speaking children who have been forced out of school.

According to Prime Minister Chief Dr. Joseph Dion Ngute, “…in 2017, the number of enrolments in schools in the Northwest region was 220,000.”

Last academic year, enrollment stood at 60,426, a 72 per cent drop due to the conflict between the national army and armed separatist groups.

However, this drastic drop is even an improvement in the figures recorded between 2017 to 2019, which stood at 34,000 in 2018 and 24,350 in 2019.

Overall, school enrollment in the Southwest and Northwest regions increased from 185,008 in the 2018/2019 school year to 194,482 during the 2019-2020 academic year. This is an improvement from the two previous academic years when enrolment stood at 54,834 and 91,797, respectively.

While the government has been struggling to convince the population that it is winning the fight against Anglophone separatists, especially as it concerns school enrollment, the bleed on the English language school system to French-speaking Cameroon continues unabated.

“Go to Yaounde, Bafoussam and Douala and see the number of school infrastructures going up there. The speed at which school campuses are mushrooming in Francophone Cameroon is incredible. And as the number of schools in French-speaking Cameroon increases in order to accommodate Anglophone school children, so also is the number of schools closing down or forced to close down in Anglophone Cameroon increasing,” declared Ajong Wilson, a secondary school teacher in Douala who was forced to cross over to Francophone Cameroon when the private secondary school where he was a teacher in Northwest was forced to close down.

The closure of hundreds of schools has been exposing girls to a heightened risk of early marriages, survival sex, street trading or even child labour to support their families.

Many private school proprietors in Anglophone Cameroon have also been rendered bankrupt.

“I had to borrow millions of FCFA from the bank in order to increase the capacity of my school to accommodate the increasing number of children who were knocking at the doors of the school for admission before 2016. Then the Anglophone crisis came and separatists started burning down schools and preventing children from going to school. Parents withdrew their children from my school and took them to Bafoussam and other towns in the western region. Today, grass has completely covered the new infrastructures I constructed with the money I borrowed because the school has closed down. And the bank is on my neck for their money. Sometimes I seriously think of committing suicide because if this thing does not end soon, there is no way I will be able to repay the money I owe the bank,” one school proprietor who opted for anonymity told HumAngle yesterday in Douala.

Outside the school protective environment, young girls are more exposed to violence and abuse of all forms. Other out-of-school children are likely to be more exposed to abuse or exploitation, and they may get involved in activities which place them at risk, including abusing substances and recruitment by armed groups.

Fleeing conflict, most internally displaced persons (IDP), children, and youths are especially vulnerable due to lack of birth or identification documentation.

In the northern regions of Cameroon, Boko Haram terrorists have been visiting a similar scenario on the educational system in the three northern regions, especially in the Far North.

Boko Haram attacks in the country are characterized by the burning of schools, destruction of classrooms, and abduction of schoolchildren. Thousands of children in northern Cameroon, including many refugees from neighbouring Nigeria, are not able to go to school because of cross-border attacks by insurgent groups.

After being out of school for so long, for many children, the priority is not only to get an education but the necessity of psychosocial follow-up and assistance to manage the trauma they have had to experience.

Internally displaced and refugee families have faced financial difficulties in their new refuge, considering they had lost their means of livelihood and could not afford school fees, amongst other needs.

Others, particularly girls’ families, avoid school due to the high risk of abduction, especially after the Chibok incident, where over 200 schoolgirls were abducted by Boko Haram in Northern Nigeria in 2014, prompting global outrage and several campaigns to #BringBackOurGirls on social media.

Attacks on school structures and staff, which have slowed down to an extent in the Far North region, not only affect the right to education but also increase the risk for some children to be forcibly recruited by armed groups.

The state of education in the Far North Region of Cameroon was rendered even more precarious by a crisis which met an already strained education infrastructure. A report by the Friedrich-Erbert-Stiftung Institute Cameroon indicated that the literacy rate of persons over 15 years of age stood at 40.1 per cent in the Far North as against the 74.3 % national average.

The onslaught on education does not only affect the Cameroonian children in the attacked regions but also the refugee children coming from neighbouring Nigeria who had fled to Cameroon due to the Boko Haram insurgency.

Upon his visit to Minawao camp housing most Nigerian refugees in Northern Cameroon, Filippo Grandi, the head for the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Cameroon, declared: “I am convinced that education is the most important investment that we have to make in the Lake Chad region now and in the future to avoid a repeat of the events and of the horrible abuses of the last years.”

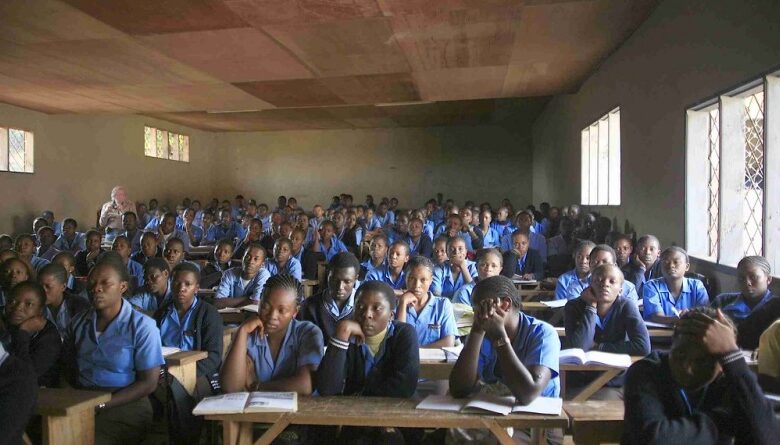

The education needs of the affected populations have so far been supported by various governmental, non-governmental and international efforts and initiatives. As much as their efforts must be applauded, the lack of trained teaching staff, learning material, school structures and overcrowded classrooms still pose a threat to the right to education.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter