Fear Of Boko Haram Not Enough To Protect Borno’s Forests From IDPs

Desperate, IDPs in Northeast Nigeria are plunging into the forests for their daily bread, despite the danger posed by lurking terrorists and the risks posed to the environment.

Opposite Dalori II displacement camp, located at the outskirts of Maiduguri, Northeast Nigeria, is a mound of hay, nearly six feet tall and twice as wide. It had been torched and now the fire smoulders gently, with smoke escaping from one side. Buried inside are big logs of wood that will turn to charcoal in a few days. Two young men guard the hill with a rake and spade to keep it in shape. Others sort through an assembly of axed tree parts lying around.

Abubakar Ibrahim, 40, who leads this team of loggers and charcoal manufacturers, is an Internally Displaced Person (IDP) from Ashigashiya, a town in Gwoza Local Government Area (LGA) that lies on the border with Cameroon. In 2014, the notorious terror group, Boko Haram, had hoisted its flag in the town and declared Gwoza its headquarters. About a year later, Nigerian troops recaptured the area, giving room for locals to rebuild their lives elsewhere.

Abubakar chose Maiduguri, Borno’s state capital. And with Boko Haram still actively operating in Gwoza — even particularly Ashigashiya, he has not looked back.

Of the over 2.1 million IDPs in Nigeria, Borno State alone hosts roughly 1.6 million. Every morning, thousands of them, mostly middle-aged men and women, set out on foot and in old pickup trucks, hoping to return hours later with a piece of the surrounding forest area. They use some of the wood they gather for cooking and sell the remaining to take care of various essential needs.

Most of them, previously farmers and cattle herders, lost their livelihood to the insurgency. While there are relief programmes that provide foodstuff and cash allowances on a monthly basis, not everyone benefits. Those who do, complain that the support does not sustain their households through each month so they are forced to seek other ways of making ends meet. One of the most obvious ways is cutting down trees in the forest that can be used as fuel and trading them for money and valuables. A few like Abubakar first convert the wood to charcoal, another cooking fuel that is popular among locals.

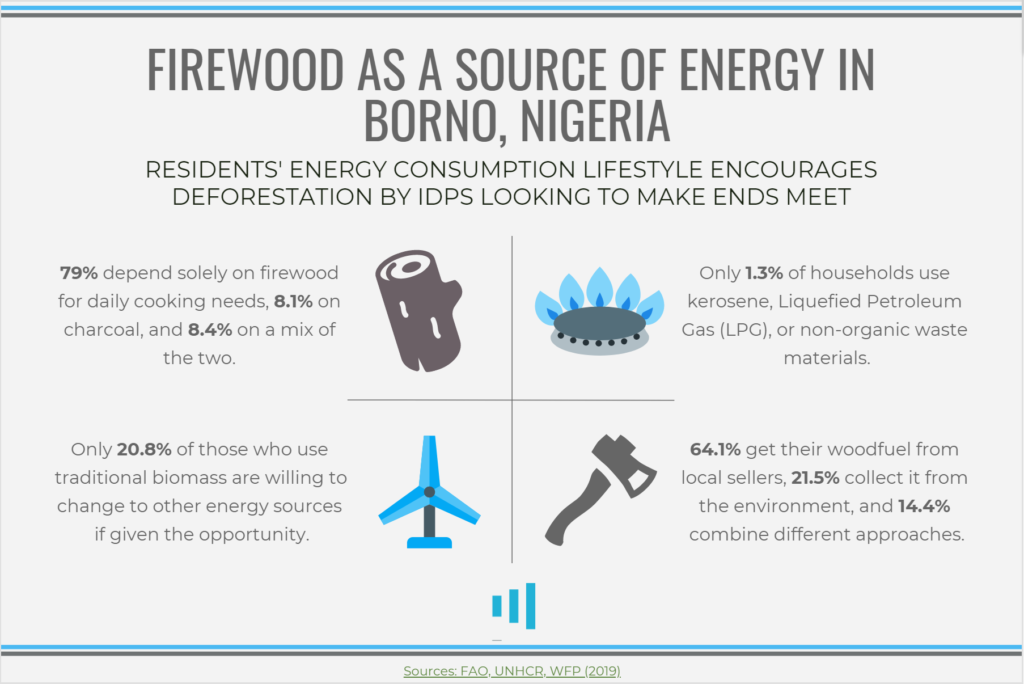

Despite the significant adverse effects the practice has on the forest areas, it has continued to thrive. One factor responsible for this is the accessibility of fuelwood and the lifestyle of residents generally. Fuelwood is used for domestic cooking, commercial beef roasting, and in bakeries. Forest resources are also used for construction and medicinal purposes. A United Nations study conducted in 2019 showed that up to 95.5 per cent of the households in Borno relied on firewood and charcoal for routine cooking, with two-thirds getting them from local sellers. Also, only 21 per cent of those surveyed said they would change their energy source if they had a chance to.

Abubakar was a farmer in his hometown but, in Maiduguri, similar land resources are not available to IDPs. So he took to combing the forests for fuelwood and has been doing so for the past six years.

“I go to the bush from time to time with 10 of my boys to get the wood,” he tells HumAngle, sitting on a pile of branches. “I started it for the first time when I came here and became a boss in the business.”

Aside from the 10-man exploration team, he has 20 other people working with him to produce charcoal. While the IDPs mostly do not discriminate between one type of tree and the other, Ibrahim’s men target the Gawo, Neem, and Tamarind, preferring the last two because they make better charcoal. They sell their products to members of the neighbouring Dalori II camp and traders from downtown.

A struggle for survival

The members of Muna Garage, a displacement camp between Maiduguri and Jere LGAs, are renowned for felling trees in the forest around Abu Guddum, Amarmari, Masarmari, and Zerozero. The camp is estimated to have over 7,300 households and about 39,500 IDPs from various parts of Borno. At least 500 of them are observed to make trips to the forest every morning to chop down trees. According to them, this is because of a dire need to survive.

“It is due to poverty,” laments Agah Ibrahim, 55, who used to farm and rear cattle before he became displaced from Amar Bari, a village in Mafa LGA. “We need something for our livelihood and to feed ourselves. What the government gives us is very small [and] we don’t know any other job except this one.”

Boko Haram terrorists had seized their foodstuff and livestock in Amar Bari, forcing them to resettle in 2015. But when they arrived at where Muna Garage camp is today, it was just a large tract of vacant land. They had to set up their tents themselves and only managed to get by. About a year later, Agah looked in the direction of the forest and saw a glimpse of hope.

The business is a free-for-all, but it is mostly the IDPs who are desperate enough to risk their lives to do it — some as many as five days a week. The tree trunks are reserved for the charcoal manufacturers while the smaller branches are sold as firewood. The price ranges between N100 and N500 per unit, and then a truckload of wood costs around N50,000.

Although hardship pushed him into the business five years ago, Agah is not doing too badly. Today, he makes an average monthly profit of N35,000. This is after he has paid the five to six people who work for him their daily wage of between N1,600 and N3,000. With this money, he takes care of his large family of three wives and 20 children — six of whom were born here in Maiduguri.

Mala Yaga, 50, who has two wives and nine children, explains that he is into felling trees so he can feed his family too. Also, unlike other businesses, gathering firewood does not require a big capital. “If I can get enough capital like N100,000, I will leave it to start a new business of selling provisions,” he promises.

Among the IDPs who constantly probe the forest as a means of survival are also scores of widows, often over the age of 40.

When the insurgency spread to Ganama Ibrahim’s village, Malumri, in Mafa LGA, her husband persuaded her to escape with the children. That was six years ago and she has still not reunited with him. The people from the area tell her they have not seen him. So, the burden of caring for the family has since rested on her frail shoulders.

“It is very difficult. We go on foot and sometimes we go in a pickup. We walk long distances and come back in the afternoon. It takes us five to six hours sometimes to go and come back,” she says. “But we have to go because we would sell it and use the money for survival.”

Ganama often returns from the forest with two bundles of firewood. She sells one for N500 — or as much as N1000 if she is lucky — and uses the second to cook.

Yagana Agah, 40, who is from Boboshe, another community in Mafa LGA, has lost her husband as well. He fell sick and died before she migrated to Maiduguri in 2015. She has six children, aged four to 10, and has not been included among the beneficiaries of the monthly food donations by the state authorities.

“Most of us that don’t have husbands depend on firewood to survive. A pickup would take us to the bush and bring us back. We bring three units, two for us and the other for the truck’s owner because I don’t have money to pay for the hire,” she says.

From the little she makes from selling the two units, she buys maize grits, seasoning, and dried fish to cook for herself and the children. But the line of work has started to tell on her health. She coughs repeatedly during the interview and complains of body pain and a headache.

“I used to go [to the forest] every day before, but now I only go sometimes. I am even sick and haven’t gone for about a week now,” she says.

Anytime Yagana is not strong enough to make the trip, she resorts to begging for alms. Her children are still too young to fetch firewood, but her 10-year-old son supports by working as a baggage carrier at a nearby market.

“Our problem is food and there isn’t enough water. We want them [the government] to provide enough food for us,” she tells HumAngle.

The environment bleeds

Forest areas in Borno have ordinarily been damaged due to the heavy reliance on firewood and lack of regulation guiding how it is collected. But the displacement of millions of people due to the Boko Haram insurgency has further worsened the problem. Apparently, this challenge is not limited to Nigeria. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 80 per cent of the 65 million people displaced worldwide rely on traditional biomass fuels, especially wood, for cooking and heating.

“The massive increase in demand for wood fuel for cooking caused by sudden influxes of refugees and other displaced people is usually the main driver of forest degradation and deforestation in displacement settings,” it states in a 2018 report.

But the more vegetation and trees the environment loses, the more it is exposed to climate change, desertification, soil erosion, flooding, as well as the loss of animal and plant life.

All the IDPs interviewed by HumAngle observe that the forest areas around the displacement camps have shrunk massively since they started felling trees about six years ago.

“We started with about a kilometre from here and moved gradually to five to six kilometres from here; so the trees are all affected,” admits Agah. “Also, when we go out early in the morning, we used to come back before afternoon because we didn’t go far. But now, we will be in the bush until afternoon.”

Abubakar says the same thing about the forest area around Dalori II displacement camp. Some of the animals they have spotted during their trips are gazelles, rabbits, and squirrels. As the forests shrink, their habitats are affected as well, and it is only a matter of time before they become as elusive as the wilder animals.

A Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis of the change in vegetation within a 10 km radius of the Dalori II and Muna Garage camps further reveals how grave the problem is. While the vegetation in the places respectively covered an area of 47.3 square km and 65 square km in 2011, they have shrunk, a decade later, to 22 square km and 45.4 square km.

Desertification in Nigeria is estimated to threaten the livelihoods of over 40 million people, with Borno being among the eight most affected states.

There are efforts from both the state government and civil society groups to undo the damage done to the environment, especially through tree planting. In 2017 and then again in June, this year, the government announced a ban on the sale of charcoal and firewood along the streets of Maiduguri to prevent pollution and discourage tree felling. But when HumAngle visited in August, the roadside vendors still had their shops all over the city.

At the national level, the country established an agency in 2015 to implement the multinational Great Green Wall (GGW) programme. Also, last year, Nigeria’s President Muhammadu Buhari, approved the planting of 26 million trees to reduce the impact of Climate Change. But the pace of all these programmes appears to be too slow compared to the rate of logging.

Dr Usman Ali Busuguma, regional director of the African Climate Change Research Centre (ACCREC), a non-profit based in Northern Nigeria, says that before the people of Borno were displaced, most of them also felled trees for their cooking needs. The only difference is that it is now done on a commercial scale because the forest is seen as a “free gift from God.”

He points out that another often overlooked way the insurgency has contributed to deforestation is that Nigerian soldiers often cut trees to prevent ambushes by Boko Haram militants and improve visibility.

Dr Busuguma urges the government to empower IDPs with other livelihoods, make cooking gas affordable through subsidies, step up sensitisation about the downsides of using wood fuel, train locals on alternative sources of energy, and continue to encourage the planting of trees.

Different IDPs tell HumAngle they have heard protests from the state government about their work. They, however, add that those complaints are not about the forest but rather focus on the dangers posed by the activities of terrorists.

“Yes, we are aware our activities cause deforestation and that the wild animals would vacate the area,” Mala says simply, “but we have to do it to survive.”

A death-defying venture

For the IDPs in Maiduguri who are into fetching fuelwood, survival does not only mean putting food on the table, battling stress, or going to the forest with pain relief medication, it also means escaping the clutches of Boko Haram terrorists. This is because while their security in the town is relatively guaranteed, the risks escalate once they cross into the forest area. But the dangers posed by the terror group is not enough to keep them away from the trees.

“We used to fear getting attacked by Boko Haram before but we are used to it now,” says Ganama.

Whenever they suspected terrorists were close by, they would run and hide in the bush. But this has not stopped many of them from falling prey. While the women are often abducted, the men suffer a more definite fate.

“They would not even ask you [any questions], they would just kill you when they see you,” says Abubakar, who has lost over 40 of his colleagues to the brutality of Boko Haram since he started the business.

He adds that he is alive only out of sheer luck. Sometimes the killings took place before he embarked on the trips and, other times, just after he had returned from the forest. The frequency of the attacks has, however, reduced, especially since “no one has been killed in the past 90 days.”

“We still go because we have no other source of income. We don’t have any assets to sell and start a new business and we have no one to help us,” Abubakar complains.

Agah says he has been lucky not to have encountered the militants too, though the attacks take place about once a month.

Meanwhile, many women have been kidnapped, forcefully married, and raped by terrorists lurking in the forests. Some, like Balu Agah, have managed to escape and return to the camps, while others are still stuck. Balu had gone to the forest area with about a dozen other women and one male escort in September 2019 when the group was attacked. The man was killed on the spot and another woman was slaughtered much later as a scapegoat to discourage them from running away. When she finally escaped about a year later, it was with an eight-month-old pregnancy.

When she spoke to HumAngle in 2020, Balu had mentioned two other abducted IDPs who were pregnant and were told they had to give birth before they could be married off. One of those women was Yasulum Bello, 30, who only returned to the camp in May, this year, after spending a year and seven months in captivity.

“They took 10 of us and killed one on the way when she refused to go. When we went there, they married all of us except for the three pregnant ones among us. I was also pregnant and I was married after I gave birth to my child,” narrates Yasulum, who has a broad, infectious smile that tends to show only her upper teeth.

“They enrolled us into their Islamic school and made us grind corn for them … It was terrible; they killed the man with a gun and the woman was slaughtered. They forced us to watch and said anyone who tried to escape would be treated like that. It was the first time I witnessed [someone getting slaughtered]. I was shocked. I was always afraid of being killed and thought about my children.”

Though she admits that food supplies were more abundant in the terror camp and she sometimes had access to chicken and goat meat, it was the thought of her children back in Muna Garage that pushed her to escape. Her Boko Haram husband, Umar, had gone away on guard duty for two days and she seized the opportunity.

“I sneaked out alone when he was away. I didn’t follow the normal route; I walked for six days and luckily didn’t meet anyone on the way,” she recalls.

Yasulum’s family gets 10kg bags of maize, beans, and rice every month from the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) but it is not enough to feed her, her in-law, her husband, and their six children. To survive each month, they sell the bags of rice and beans and instead buy guinea corn because that would last longer — up to two weeks. Then the husband, Bello Yuguda, farms and fetches firewood.

Now that she is back safely, Yasulum, like the younger Balu, has abandoned her previous line of work. She now offers her services to farm owners in the host community for a daily pay of N800. It may not be as lucrative as what the forest promises, but it is better than nothing and safer too.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter