Escaping Terror (1): An IDP’s Journey From Borno, Cameroon, To Yola

Hannatu was forced to abandon a cushioned life as a teacher in Borno State, Northeast Nigeria, taking refuge in the border town of Cameroon after trekking for about 10 hours.

Madam Hannatu had a beautiful life before everything fell apart.

There were the afternoon, evening and night lessons she loved at the Women’s Teacher’s College in Maiduguri, Borno State, Northeast Nigeria. This experience was made even more memorable with the mix of foreign and local teachers like Master Abraham Opare, her Ghanaian English tutor nicknamed Operation of English. There was also her Indian Biology teacher and the head teacher from Borno.

A good life

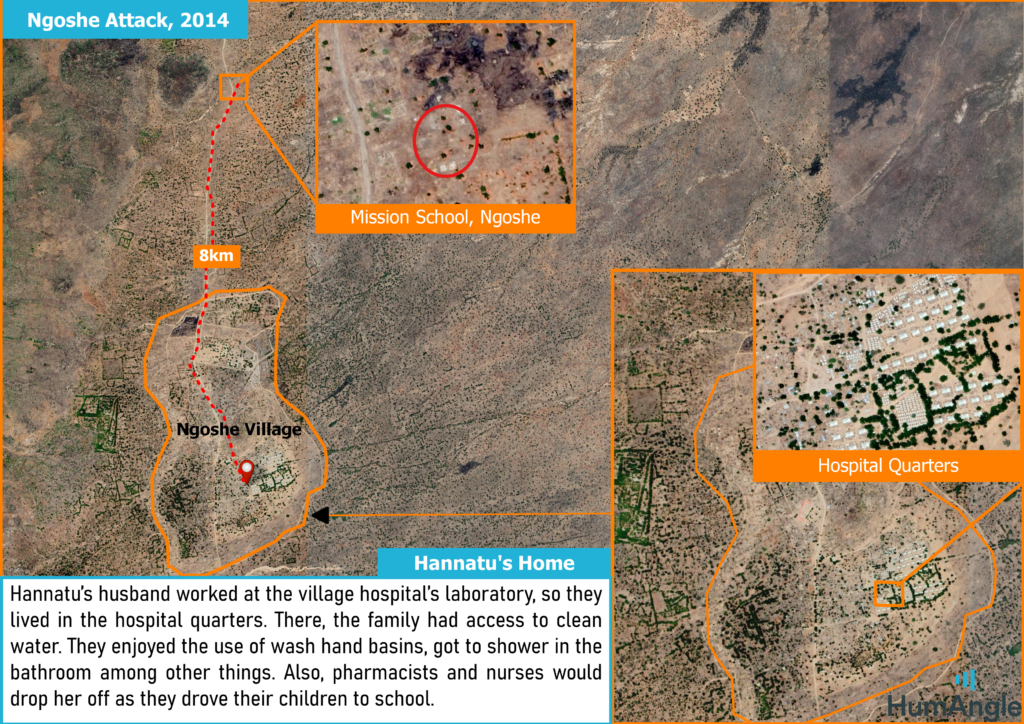

After her training at the teachers’ college, she went back home to Ngoshe in Gwoza Local Government Area (LGA) of Borno State. In 1991, she worked for the Census Board and in 1992 was recruited by Americans who established a mission school in her village, where she would go on to teach for 20 years.

Hannatu’s husband worked at the village hospital’s laboratory, so they lived in the hospital quarters. There, the family had access to clean water. They enjoyed the use of wash hand basins, got to shower in the bathroom among other things. Also, pharmacists and nurses would drop her off as they drove their children to school. Life was indeed good.

Today, the rather small woman seated opposite a primary school in Kuchingoro IDP camp is one of Borno’s displaced. Her touching story begins from when she fled with her children at the peak of the Boko Haram insurgency to neighbouring Cameroon.

Accepting Boko Haram

“Christians and Muslims were communicating and living in peace. During Christmas celebrations, we would cook food and give them and they would come to our celebration…During Sallah, they would equally cook food and give to us,” Hannatu remembers.

Life went on smoothly for everyone in Hannatu’s universe, until 2013 when Boko Haram killed three people in the marketplace. After that, they returned a second time and killed one more person, and a third time, killing three persons in the church.

After the church attack, fear gripped everyone in Ngoshe. People no longer stayed out late for fear that they might be harmed.

In 2014, the situation in Ngoshe grew into full blown chaos — “Most of our children who were living in other states were the ones that accepted Boko Haram… We that were in the village, both Muslims and Christians, never wanted Boko Haram… They [Boko Haram] entered our village through those that lived inside,” Hannatu told HumAngle, adding that the young people who lived in Ngoshe would invite their peers (who were Boko Haram members) to visit and then they would stay.

The elders in the village warned the young to desist from the trend, but they continued anyway. With the infiltration of Boko Haram members into the village came intense fear and distrust: “Muslims would go to one side and christians would go to the other side. We as christians were afraid of them because Boko Haram started through them and not through us. We started fearing them and separating from them and that was how everything fell apart.”

Soon, parents quit sending their children to school and people stopped daily activities they thought were likely to put them in harm’s way. Chaos was brewing.

In April 2014, the villagers began to see even more strange faces around. The threat that was Boko Haram was hanging over Ngoshe like a dark cloud. When word got round that Boko Haram had threatened to abduct Hannatu and make her tutor their children or kill her if she refused, people urged Hannatu to flee the town. She refused. People ran helter skelter and the men fled to the mountains because Boko Haram started slaughtering males who were up to the age of 18.

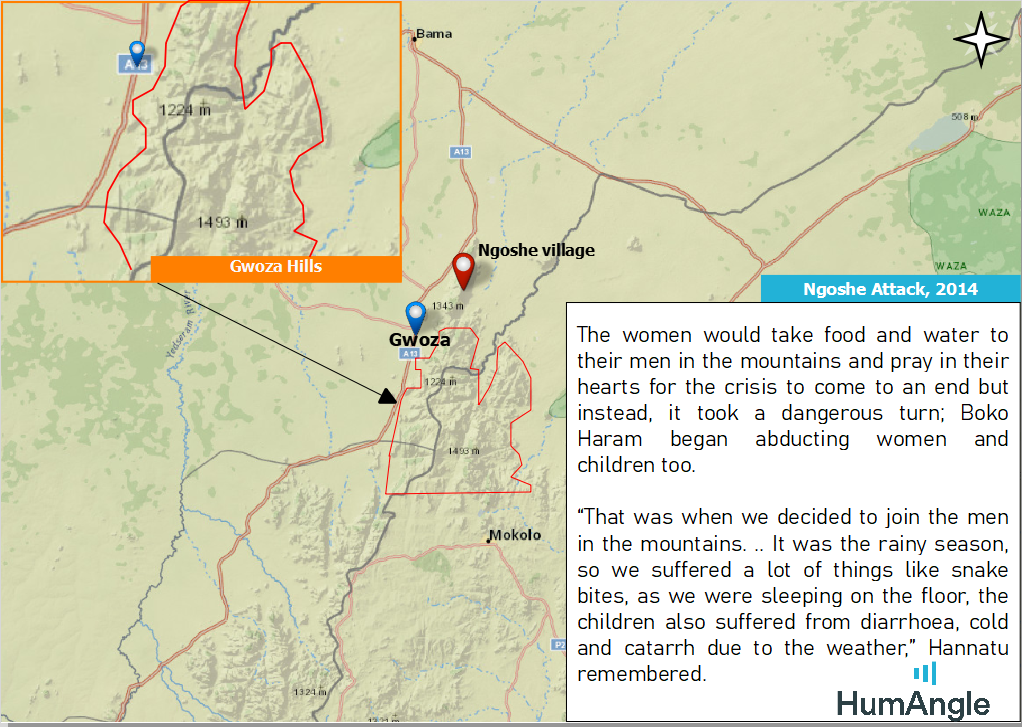

The women would take food and water to their men in the mountains and pray for the crisis to come to an end, but instead it took an even more dangerous turn. Boko Haram began abducting women and children too. “That was when we decided to join the men in the mountains. It was the rainy season, so we suffered a lot of things like snake bites, as we were sleeping on the floor, the children also suffered from diarrhea, cold and catarrh due to the weather,” Hannatu remembered.

Ngoshe was already a shadow of itself and so was everyone in it. Education was halted and so was everything else. To make things worse, Boko Haram fighters followed them to the mountains. “Whenever they come to fight with us, we defend ourselves with this gun that hunters use in the bush,” Hannatu said.

Hannatu and her folks did not think that the situation would get any worse, except that it did; Soon enough, Boko Haram brought foreign fighters with them and, with the foreign fighters came machine guns and even more sophisticated weapons. “When they felt that we were going to survive, they went and invited plenty of people from far and wide, even from different countries. Some of the men they invited had big and long beards and they tied their heads, leaving only their eyes,” she said, describing fighters that might have come from other sub saharan African countries in the lake chad region.

“They killed some of our men, took the women and children, gathered them in one house and kept them like slaves. They would buy okro, garri and food seasoning, then give them to the women to cook like that in order to feed themselves and the children.”

This was when Hannatu made the decision to flee Ngoshe with her children aged three and 12 and her sister’s 10-year-old.

From Ngoshe To Cameroon

On April 12, 2014, Daily Post reported an attack that took place in Hannatu’s village. According to the report, Boko Haram fighters had invaded Ngoshe at about 10 p.m. WAT and opened fire on already sleeping residents, killing 30, injuring several others, and setting some residential buildings ablaze. A few days after that attack was when Hannatu decided it was time to leave while she could.

With her three-year-old strapped to her back, the other two children by her side, Hannatu came down from the mountain in the company of others who were brave enough to escape.

A woman had to leave her crying child behind in order not to compromise the safety of other travelers. “We could not flash light because if we did that, they would trace where we were passing through,” she recalled

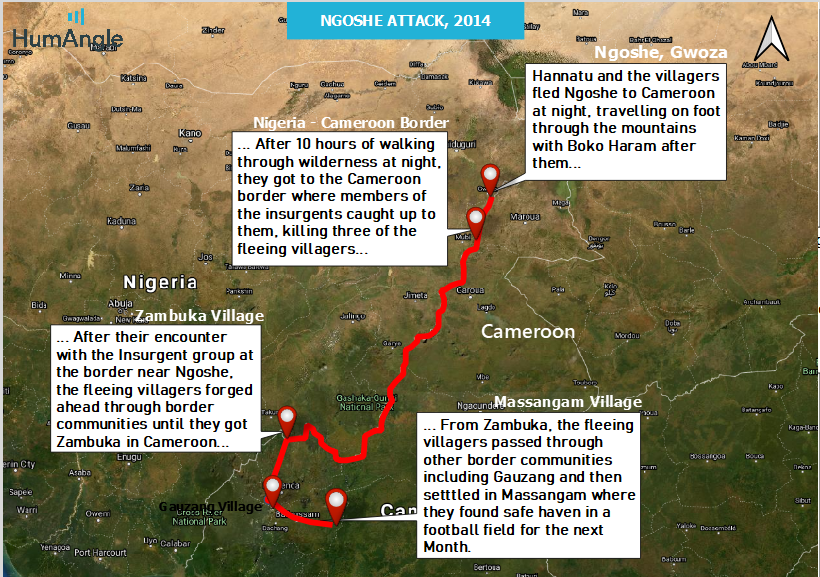

Hannatu and other villagers fled Ngoshe to Cameroon by 10 p.m. WAT that night. They trekked barefooted in order to minimize noise and avoid detection by the insurgents.

Traveling on foot, they would pass through the hills and valleys of the Gwoza mountains and parts of the Mandara mountain range as they traveled southwest towards the Cameroon border. Along this path, the terrain is not plain, but rather slopey and wavelike, with grasses growing all over the landscape and the ground filled with dead leaves and twigs from surrounding trees and plant communities, all of which must have taken a severe toll on the travelers, leaving them with sore feet.

The mountains are some of the highest in Borno State as some peaks rise above 1200 meters above sea level. The grounds of the valleys still measure high elevations averaging some 300m above sea level. Hannatu and her companions had to travel up and down hills on their way to Cameroon.

After 10 hours of walking non-stop through the wilderness, they got to the Cameroon border.

“We suffered a lot, every single one of us. We spent the whole night trekking before we got to the Cameroon border around seven in the morning. They [Boko Haram] even followed us to that border and shot one nursing mother who was breastfeeding her two-month-old in the right breast and two other men,” Hannatu told HumAngle.

Progressing southwards after the border, they continued to meet this same arrangement of elevation and vegetation. After their encounter with the Insurgents at the border near Ngoshe, they forged ahead through border communities until they got to Zambuka.

From Zambuka, they passed through the border community of Gauzang and then settled in Massangam where they found safe haven for the next month living in an open field.

From Cameroon To Yola

Without money to take her to Nigeria, Hannatu and her children were stuck in Massangam. They would remain there for one month and two weeks, scraping together whatever she could to ensure that her children survived.

Hannatu and the other women from her village fetched firewood from a nearby forest and built a tripod fireplace where they cooked whatever they could lay their hands on. They fed mostly on pap. Whenever they could, they would go to Massangam and Nashawa market.

Sometimes, it felt as though she had imagined it all— the hospital quarters where she lived with her husband and children, the running shower and other amenities. In Massangam, Hannatu was stripped of all that privilege. For example, she had to go to the stream with the other women to fetch water.

“When we get to the stream, we will dig a hole and drink from it, fetch for cooking and also do our washing. Cows also drank from this same stream,” Hannatu recalled.

Help came when “some of our people in Nigeria who heard that we were sleeping in an open field contributed money and brought the truck that transports cows, and took us to Yola.”

They were packed in a rickety lorry which usually conveyed cattle for interstate trade. Hundreds of swarming bodies, squished together like human sardines, yet grateful that a better life awaited them in Nigeria.

As they made the 375 kilometer journey to Girai 11 Primary School (temporarily converted to an IDP camp) Yola, Hannatu did not foresee the type of life that awaited her there. For now she was grateful that she did not have to sleep in the open again, grateful that she did not have to dig with her own hands for water from the same source as cows.

This story was produced in partnership with Civic Media Lab under its Grassroots News Project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter