Displacement Camp No Longer a Place of Refuge for Maiduguri’s IDPs

Boko Haram terrorists are invading an IDP camp at the heart of Borno state in northeastern Nigeria and abducting displaced people, who usually have to sell most of their assets or borrow money to raise huge ransoms. Some of the victims have now relocated someplace else where they feel safer.

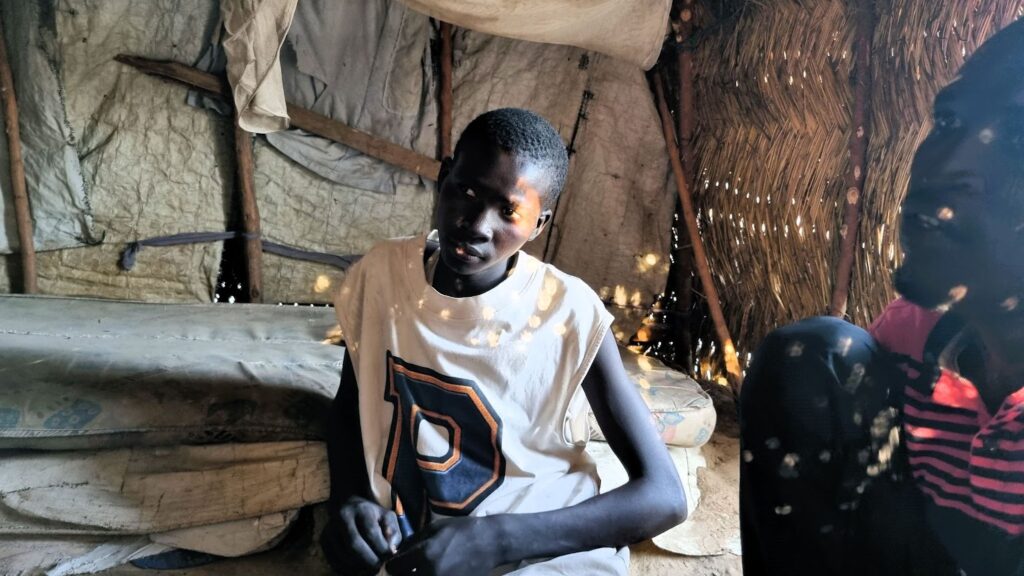

It was midnight. Yasin Dogo, 25, was fast asleep when someone tapped his neck. He opened his eyes, expecting to see his wife or one of his children. Instead, he was staring down the barrel of a gun. Boko Haram terrorists had snuck into the Muna Garage camp for internally displaced persons, looking for people to kidnap. One must have climbed in through the window and opened the door for the others. There were five of them. One was dressed in military uniform. Three had guns.

Yasin was defiant still. He asked what the intruders wanted.

“They responded that nothing had happened. I said that something must have definitely happened. If not, they would not have pointed a gun at me in the middle of the night inside my room.”

The terrorists told him not to panic, but by this time, one of his wives had woken up, too. She nearly screamed, but they threatened to shoot Yasin if she caused a commotion. Two armed men held both his hands and dragged him into the cold darkness. A third terrorist kept pointing a gun at his back. When they got close to the outskirts of the city, they offered Yasin two unpleasant choices: You either come with us, or we kill you.

Yasin complied. They spent the rest of the night walking. He recalled passing through a forest in Kauri, known as Gazuwa. Before dawn, they had reached Ngoom Forest, where they finally stopped to observe the subh (morning) prayer. Then, they resumed the journey for a few hours. By 8 a.m., they rested somewhere for the rest of the day and nourished themselves with bottles of waterlogged garri. At sunset, they continued again, walking throughout the night until they reached the terrorists’ camp the following morning.

“I spent five days in captivity.”

Yasin was displaced eight years ago from Ngamdua, a community in the Mafa area of Borno, northeastern Nigeria. Since then, he has found shelter at the Muna Garage camp in Jere — a local government area that hugs the capital city of Maiduguri and is often seen as a part of it. His kidnapping was the first in a series. The abductions have become so frequent, happening almost weekly or biweekly. Ahmadu Aga, a community leader within the camp, disclosed that there were five successful abductions in the two months between the end of June and the end of August that affected IDPs from the Dikwa local government area. Eight people were kidnapped during these incidents. Two other attempts failed because women sighted the terrorists on time and raised an alarm.

Usually, when someone is abducted, other IDPs would rally around to raise their ransoms, which could be up to ₦1.5 million. Such crowdfunding efforts became so frequent that the displaced people had to establish committees to coordinate them.

In the past, abductions like these were only common in the remote farmlands and forest areas on the outskirts of town. Once they returned to their shelters in the evening, the IDPs in the area generally felt safe from the bloodthirsty blades of the violent extremist groups. But this is no longer the case. Various victims who spoke to HumAngle mentioned that there was no presence of security personnel on the routes the terrorists took from the town to their strongholds. Meanwhile, the camp is only a 30-minute drive from the state government house and the police headquarters in Maiduguri.

In Yasin’s case, the terrorists blurted out their demands when they reached their hideout. Ultimately, they would only let him go if somebody paid ₦4 million for his freedom. Otherwise, they would kill him. When Yasin replied that he could not afford such an amount, they said he should ask his father. They claimed to have tracked and targeted him because of some information they had obtained.

Yasin still had his phone with him, so he called his father, who asked the terrorists the same question.

“Where do you expect me to get the money from?”

“That is your problem,” the captors responded. “Do not call this line again until you have raised the ransom.”

The terrorists took their frustration out on Yasin, beating and threatening him to reveal how much his father had and what his assets were worth.

Two days later, the phone rang. Yasin’s father had not raised the ₦4 million. He simply could not. He pleaded with the terrorists to spare his son’s life and accept however much he was able to scrape together. The group initially insisted on that amount before agreeing to make it ₦3 million.

“My father still told them he could not afford ₦3 million. He said if he had such kind of money, he would not have been in an IDP camp,” Yasin recalled.

Eventually, his father managed to raise ₦1.7 million, which was good enough for the terrorists. He had emptied his savings, which had money he planned to reinvest into his farm. He got ₦100,000 from his brother and ₦200,000 from other families and friends. Then, he borrowed an additional ₦400,000, promising to pay back after the harvest season. Yasin’s two older brothers delivered the ransom.

Weeks after Yasin’s kidnapping, the terrorists struck again. It was around 2:30 a.m. on Aug. 14. This time, they went away with two neighbours at the Muna Camp: 20-year-old Abbas Aga and 18-year-old Isah Bukar. There were eight assailants. The oldest among them must have been about 35 years old. Some looked young enough to be teenagers. They had assault rifles and wore multicoloured kaftans that seemed to have been patched using different fabrics. Some of them also wore beanies.

After waking Abbas, they asked him to take them to the tent of a rich person in the camp, hoping that the gun pointed at his head would get him to comply.

“But I don’t know who is wealthy,” Abbas protested. “We are all poor people. Don’t you see our condition?”

After some back-and-forth, the terrorists decided to make do with what they had and abducted these men instead. They shoved them across the road and into the forest, beating them with instructions to hurry up. Eventually, they merged with another group with two other kidnap victims and continued the journey. Abbas would later learn that the other victims were kidnapped on their farms. When they reached the terrorists’ camp about 40 km from the IDP camp, they tied the four men under a tree, where they remained for five days.

“They said we should bring ₦3 million. We told them we don’t have ₦3 million. They said we should bring a phone number for our people and they’ll communicate their demands. We told them we didn’t have phone numbers or even phones. ‘You have searched the house and us and didn’t find any.’ They said, ‘Okay, we’ll keep you here. If you do something, we will kill you.’”

Isah raised his trousers to reveal scars, which he said were inflicted by mosquitoes during their captivity. On the sixth day, he told the terrorists he needed to relieve himself and did not want to soil himself. When they untied him, he bolted. Abbas also escaped shortly afterwards with another hostage he had been tied to while they journeyed on foot one night. The tall crops served as a cover.

When they spoke to HumAngle in late August, two weeks after the abduction, the two men had not slept in their shelters, afraid the terrorists might return for them. “We come here, to the places behind this area,” Abbas said, referring to the centre of the camp. “In the morning, we’ll go to our house.”

Terrorists have continued to abduct displaced people while they work on their farms. Modu Aga, 31, and his brother, Hassan, 15, were victims of this on the morning of Saturday, Aug. 17. Ten gun-toting terrorists ambushed them on their red sorghum and beans farm in Kolkol, a community close to Maiwa. When Modu made to escape, he realised Hassan was already trapped, so he surrendered.

“‘Let’s go,’ they said. We begged them, but they did not listen. Seven of us were abducted. They had abducted two before getting us. And after us, they caught three more,” Modu recalled.

They led them into the forest. Afterwards, they released Modu so he could gather money to return for his brother and gave him a phone number to keep in touch. They requested for ₦1 million but eventually settled for ₦500,000. This was a lot of money, and it took Modu four days to raise it. Hassan had become malnourished when they reunited because he was not offered food.

Hassan narrated that they were kept under a tree and exposed to mosquitoes and cold weather. Even though the terrorists cooked, they did not offer any food to their victims. Hassan thinks it is because they themselves “barely had enough” to eat. The Institute for Security Studies (ISS) recently confirmed a growing case of “excessive hunger” among insurgents in the Alargarno Forest area, forcing them to adopt desperate survival measures.

“I have heard about such abductions,” Modu told HumAngle. “But this is the first time I am experiencing it. I had farmed that land for five years. Before that day, I had not even seen the footprints of their motorcycle tyres.”

This incident has rendered Modu more vulnerable and unstable. He had to sell his motorcycle, which a younger brother used to make a living in Lagos, to raise the ransom.

“My business has also collapsed. I have nothing at the moment. I am only praying to Allah for some ease and comfort.”

This is especially difficult for him because he has 16 wives and children and no longer has the means to feed them. He does not feel safe enough to return to the farm, which has now become overgrown with grasses. “Even the hoes we took to the farm that day are still there,” he said. “Where will I get the ransom money if I get abducted again?”

Despite the hardship, Modu is still thankful to be alive. During the terrifying encounter, he had thought that the Boko Haram fighters would certainly kill them.

“Death. I saw death. Their presence was death,” he replied when asked what was going through his mind.

About a month after Yasin’s abduction, his family left the IDP camp — including his father and brothers. “This was not the first abduction in the family. About three years ago, they tried to abduct my brother. However, when he resisted, he was stabbed several times,” he explained. Now, they are renting a five-room apartment in Muna Kumburi, a community not very far from the camp. Yasin’s father and his wives occupied the rooms while others set up thatch rooms in another section of the land.

“We have nothing left now,” he said.

Yasin has lost hope in the government, believing that even if he made any requests from them during the interview, nothing would be done about them.

“It is Allah alone that can restore peace. But we are not safe. Right now, apart from the economic hardship, we are getting picked. We are not safe on our farms and at home. We have no peace of mind. What was saved for farming was used to pay the ransom. Another four hundred thousand was borrowed. We don’t know when the owner will come to demand his money.”

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) at the Muna Garage camp in Borno, Nigeria, live under constant threat from Boko Haram terrorists. Victims like Yasin Dogo and Abbas Aga have experienced terrifying abductions, often at gunpoint, with the terrorists demanding large ransoms from impoverished families.

These abductions, previously limited to remote areas, now occur near the camp, highlighting a severe security lapse despite its proximity to government and police establishments.

The community responds by banding together to crowdfund ransoms for abducted persons, but this drains their already scarce resources, worsening their plight. Scarcity of food among insurgents exacerbates their aggression, targeting vulnerable IDPs even while they work on farms for survival.

Many IDPs, including those from Yasin’s family, have been forced to leave the camp due to repeated abductions, which cripples their economic situation further and instills a pervasive sense of fear and insecurity.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter