Displaced By ‘Bandits’ (2): Sokoto School Where Pupils Share Classrooms With IDPs

With over 12,000 displaced people in the town, Gandi is home to nearly a third of all IDPs in Sokoto, Northwest Nigeria. Many of them share facilities with students of a primary school while waiting for help with a more comfortable environment—or calm in their respective communities.

That Mukhtar Marafa is alive today, if you ask him, is nothing short of miraculous. The young man’s village of Tabannin Gandi was besieged in June 2018. Before then, terrorists had attacked neighbouring communities, robbed them of their possessions, and seized residents in exchange for ransom.

One morning, people in Tabanni woke up to the strange sight of motorcycles, often the terrorists’ second pair of legs. Those who could, took to their heels. Some jumped into the river. Others ran towards the farmlands and forest area. Mukhtar was among the former group.

“Even though I am crippled, God saved me after I fell into the river,” he says from a kneeling position, deep vertical furrows in the middle of his brows constantly giving life to his sadness.

“I spent about two hours in the river,” he continues. “Even after the robbers had concluded their operations, nine of them on three motorbikes approached and circled me, shooting intermittently. But nothing happened as God saved me.”

Mukhtar believes the armed criminals were not after their money during this incident but “were only there to murder us.” Earlier, they had heard about the killing of five to six people from previously attacked communities. But that day, by the time the terrorists left in a haze of dust and smoke, the people of Tabanni were preparing to bury 45 of their kinsmen.

This incident is infamous today as the first bandit-related mass killing recorded in Sokoto. It’s been over three years but the shock is still obvious on their faces.

Tabanni and other villages around Gandi are located in the Rabah Local Government Area (LGA) of Sokoto, Northwest Nigeria. They were the earliest to be attacked because of their closeness to Zamfara — the first state to experience an escalation in the conflict before it spread to others. Gandi itself is about 10 km from the Zamfara LGA of Bakura. An aerial view of the two regions shows that they are not only connected by a highway, the Damri-Bakura-Tsamiya Road, but also by a rather vast forest area known as Gundumi.

Locally described as ‘bandits,’ terrorists have run amok in Northwest and North-central Nigeria for many years, killing, kidnapping, looting, raping, maiming, and extorting.

There are multiple theories about the cause of the conflict. While some experts argue that the terrorists are petty thieves who graduated into sophisticated crime owing to the influx of small arms from North Africa, others focus on the history of cattle rustling and similar injustices that have beset the country’s nomadic Fulani population as the likely trigger. Another facet is the conflict between herders and farming communities over increasingly limited land and water resources.

The problem is worsened by widespread poverty, weak governance, illiteracy, inadequate policing, and the smuggling of guns. Between 2011 and mid-2020, violence in the Northwest had killed over 8,000 people and displaced over 200,000 others. The situation has since degenerated, giving rise to an alarming humanitarian crisis.

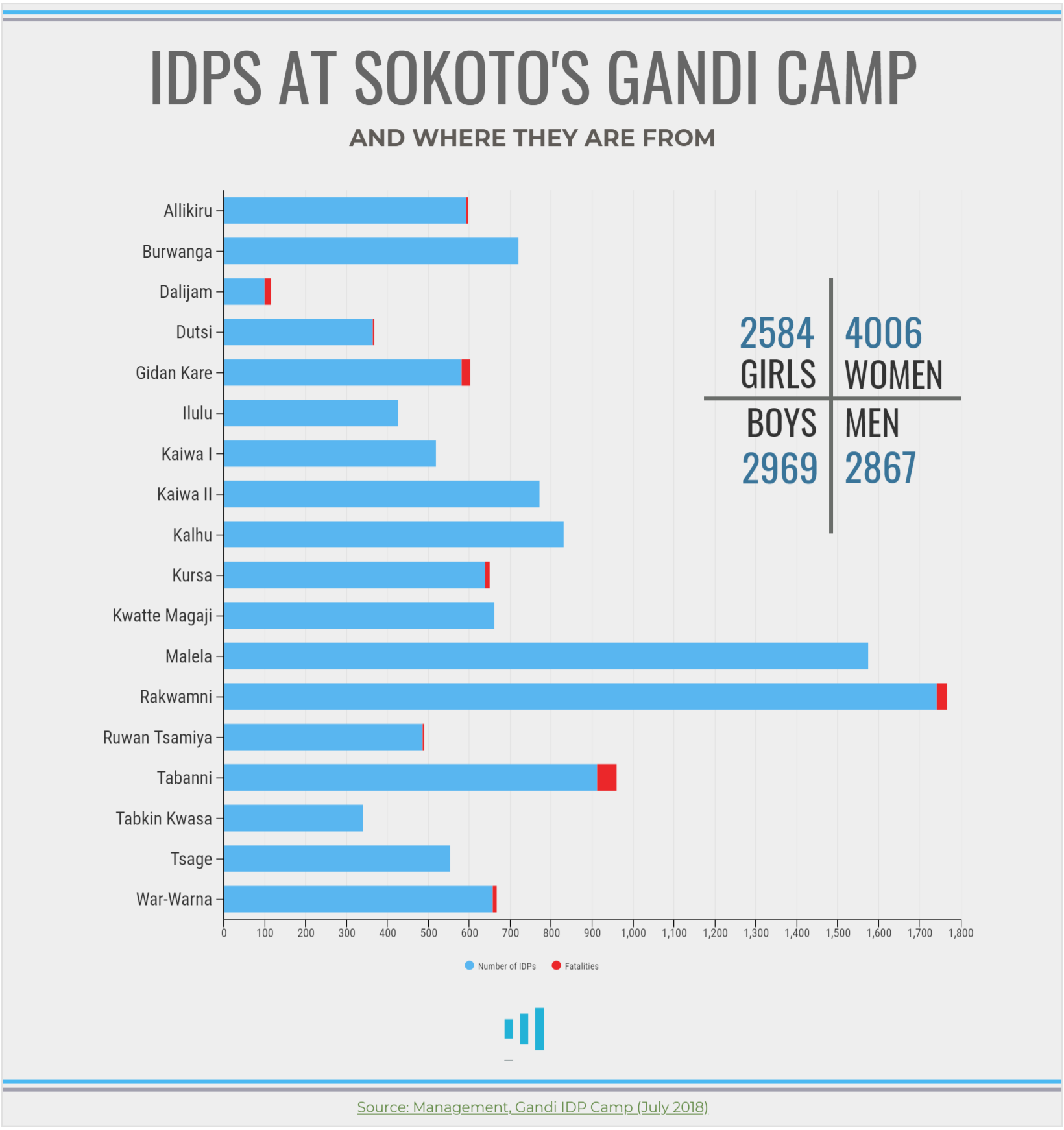

Tabanni is still unsafe. So, today, you will find most of its former inhabitants in Gandi town, where they continue to seek refuge. At the last count, there were 12,483 Internally Displaced People (IDPs) from 18 villages scattered across the town. Many of them settled at the Gandi Model Primary School. Others stayed at the nearby Government Secondary School, and those who could afford it rented their own houses.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as of last February, there were 42,241 IDPs in Sokoto. This makes the IDP population in Gandi alone 29.5 per cent of those across the state.

Meeting with HumAngle at Gandi Model Primary School, assistant camp coordinator, Ahmad Ibrahim Gandi, representing the host community, disclosed that the camp’s opening was on July 2, 2018. He then recalls the number of people from each community who had been killed in the first series of attacks. Twenty-five corpses were retrieved from the river that runs between Gandi and Gidan Kare, he says — many of them possibly jumping like Mukhtar to avoid getting shot.

Ahmad takes his leave and returns 10 minutes later with a folder full of documents. One of them contains death tolls from the various villages as well as the number of registered IDPs. Rakwamni has the highest number with 1,743 displaced people, followed by Malela, and then Tabanni. The majority of the IDPs are female. Also, among the 144 people who were killed as of when the document was prepared, 121 were male while the rest were women and girls.

At the camp, dozens of men loiter around the fringes of the unfenced school or lounge on mats under large Neem trees by the roadside. The women, on the other hand, cluster behind the classroom walls and inside the buildings. This is also where you will find, in no particular order, sizeable bundles of raffia and firewood, lines of laundry hung out to dry, all sorts of plasticware, heavy aluminium pots, wooden pestles and mortars, constantly bleating rams and goats, as well as children having fun away from their fathers’ judgemental gaze.

Though it is a Saturday afternoon, it is difficult to see how any real learning can take place in this environment any other day.

Agitated waters

“Many lives have been lost as a result of this tribulation. A total of fifty bodies were transported to Ganji. Approximately 63 members of our community were killed. Our cows, goats, and food were all set ablaze. We have lost both lives and possessions,” Lawali Abubakar, the village head of Tabanni, summarises his community’s ordeal.

Ibrahim, a middle-aged man, slouched with hands locked behind him as he speaks, sheds more light on how people from the community came to be displaced.

“These tragedies slammed into us from all sides,” he says. The terrorists started by rustling the townspeople’s animals. Then they placed a levy on them, which they reluctantly paid in the interest of peace.

One Sunday, as the problem persisted, delegates from the village set out for the town to complain to the authorities but the terrorists accosted and shot at them. When residents gathered to offer condolences the following day, terrorists stormed the town.

People scampered for safety. Some travelled to Mafara and some others to Gusau — both Local Government Areas in neighbouring Zamfara State. Later, the government sent for them and gathered them at their current location in Gandi. “Wallahi, a five-year-old child trekked for more than five hours. There were women who hadn’t seen their children in over a week until we arrived,” Ibrahim recalls passionately, pausing to let the image sink in. “All of our belongings were burned to ashes. There is no life! No money! In certain areas, you can’t even find a pair of shoes.”

It is not only ordinary people who have felt the heat of attacks. HumAngle gathered from multiple sources, including high-ranking government officials, that the state governor’s convoy was attacked in the middle of May. Soon after about 17 were killed in Gandi, the governor embarked on a condolence visit only to be ambushed by terrorists about nine kilometres from Gandi town. Residents of Tafara, where the incident occurred, said there was a gunfire exchange between the two groups, leading to five civilian casualties.

Alright, but not really

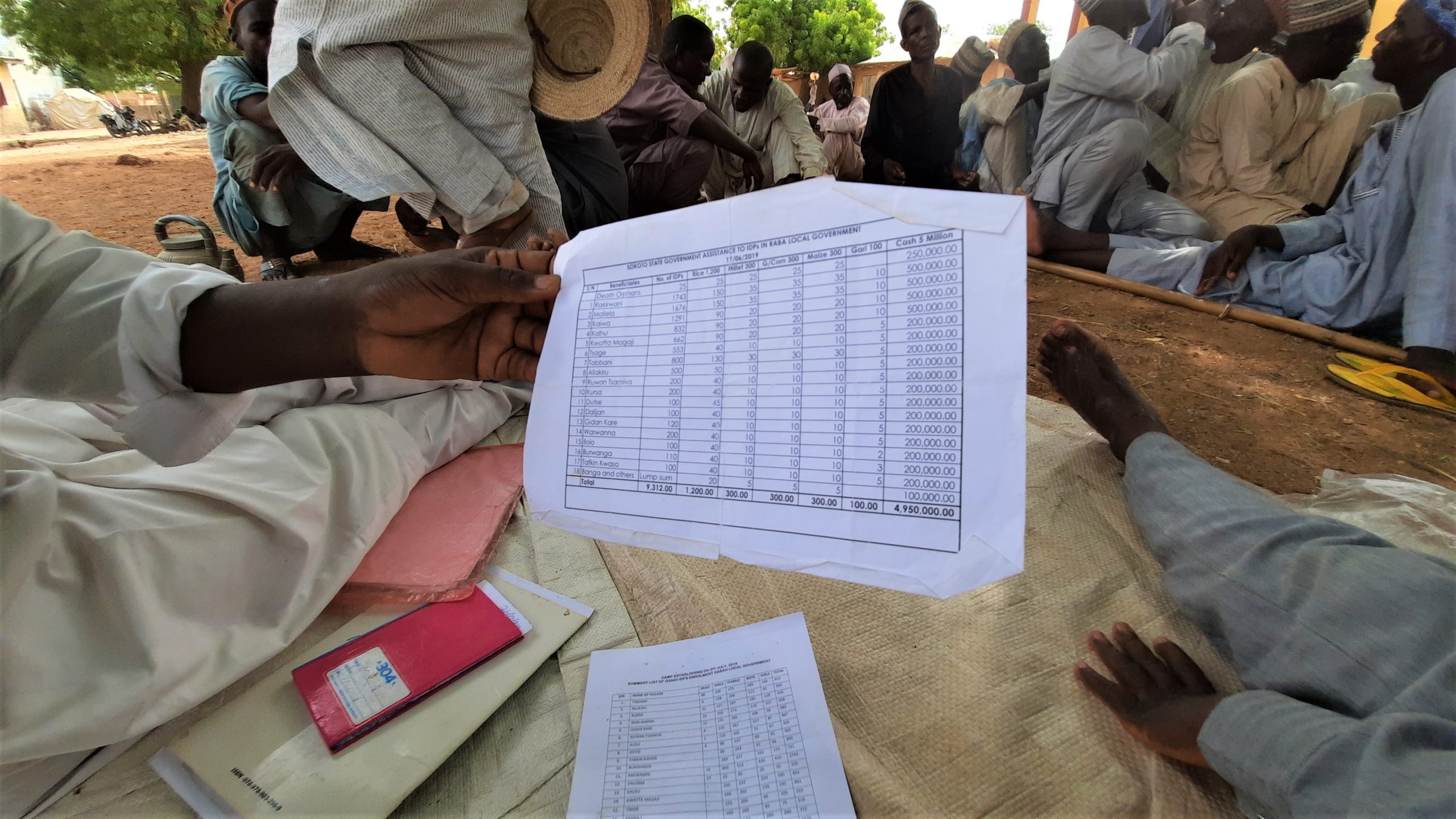

The IDPs have been receiving all kinds of support from different corners, including individuals, corporate donors, and government agencies such as the Nigerian Customs Service. A second white sheet in Ahmad’s folder has a table that shows how much the Sokoto State government donated to the 18 affected villages in June 2019. The assistance included N4.95 million in cash, 1,200 bags of rice, 300 bags of millet, 300 bags of guinea corn, 300 bags of maize, and 100 bags of garri. They have received donations of livestock too.

Ahmad says they got additional donations from the government this year. “We are expecting the Local Government to give IDPs food items today, in sha Allah,” he adds.

The IDPs also say they have been treated well by members of the host community since their arrival, “although issues are unavoidable.” But all is not perfect at this new location.

“People here have welcomed us heartily. They are really appreciated. But we are also pleading for enough shelter as we have no plans of returning to Tabanni,” says Maikudi, a fiftyish mother of five. One of the great challenges displaced persons at Gandi Model Primary School face is overcrowding. The school has a total of 15 classrooms in separate blocks. Six of them as well as two office spaces are occupied by the female IDPs while the rest continue to serve their original purpose.

“Approximately 50 women sleep in each classroom,” Lawali reveals. “They have five to 10 children with them in some cases. Men sleep outside regardless of the weather because they have nowhere else to sleep.”

There are 24 tents pitched in some parts of the premises, which the male IDPs make use of, but they are not enough. Despite their small sizes, each one accommodates about five men when it is nighttime. Some of those without bed spaces sleep inside the adjacent mosque.

The camp also lacks adequate toilet facilities. One that used to function has collapsed and the displaced people have to either make use of the tiny facility built for the mosque or, if it is unavailable, conduct their businesses closer to nature.

Another issue of concern is the loss of livelihood and inability to continue farming. When they first arrived, the IDPs were allotted lands to cultivate by the locals. They started clearing and applying fertilisers as the rainy season approached. But then, one day, terrorists crept up on them, killed three men, and made off with their cattle and camels.

“We stopped going there because of that,” explains Lawali. “Our kids used to go get firewood as well. However, when the situation became more dangerous, they were unable to do so. They now go to town and perform various tasks in order to earn money. Whatever they discover, they will bring to us.”

He expects that when normalcy is restored, the children will be able to return to the forest areas to chop down trees for sale. But that is not an option for now — “We simply come out, sit here for the entire day, and then return to sleep.”

Meeting with this reporter at the state capital, former chairman of Rabah LGA, Alhassan Ibrahim Raru, highlights another problem with the camping system.

“When you are staying in the camp, it will be just like you are staying in a boarding house,” he explains. “You as a family used to have your own house, but now you are combined with about 100 families staying in one place, sharing one toilet, sharing many facilities together. People will be lying together because the place is not very big. Women are segregated from men because of our religion; so there is no privacy. There will always be social distancing between you and your wife. There is no way you can enjoy it no matter what the government is giving you there.”

Ray of sunshine

On a vast piece of land, about five minutes drive to the west of the primary school, is a construction site the IDPs are excited about. It has 150 beige-coloured housing units, each bungalow a three-bedroom apartment. While some have been completed, others are still undergoing construction. In one part, foundations of new structures are just being laid.

At the heart of the area is a billboard containing a 3D model of what the place is to look like in the future. The design features a service area, school, mosque, and three clusters of residential buildings.

The board also reveals that the project, known as the Qatar Benevolence Village, is funded by Qatar Charity, an international humanitarian organisation that assists those hit by conflict and natural disasters. The organisation has operated in Nigeria since 2010 but, last year, it finally set up a local field office and spent $14 million (N5.75 billion) on interventions in the country.

Back at the informal IDP settlement, some are under the impression that the housing project is funded by the Nigerian authorities or that they have a major stake. “Our first request to the government is to quickly finish building the camp,” says Lawali.

“We need the camps to be completed quickly so that we can sleep with our families. A single room with over 40 persons and their families can be found here. Some people are securing locations outside, building huts to shelter them,” he continues.

“We’re requesting that the government look at our condition, particularly what we’ll be eating here. Even the things we used to be able to get are no longer available. Our people used to go out and get firewood, but that is no longer possible. We spend our days here, as you can see. We don’t even leave the house. We occasionally receive aid from the governor and Sultan. We’re pleading with them to provide us with food and shelter. Because of the people, even the farm where we were supposed to go is no longer accessible. Once you begin working, an alert will be sounded to warn you that they are approaching. You have to flee. Even the settlements surrounding the farms have been abandoned. We pray that God will help us get through this.”

Lawali adds that people will go back to their communities without question if peace returns — if for nothing else, so they could at least access their farmlands, half of which are located within neighbouring Zamfara. In the meantime, however, “the situation remains out of control.”

Still holding on to his transparent file bag, the camp administrator, Ahmad, reflects on the crisis with grave concern written on his face.

“The situation is deteriorating by the day. They’re getting closer,” he says. “They were here for several hours the last time they came. They began at 1:00 a.m. and the operation lasted until 4:00 a.m. They murdered people. Corpses were hauled here. If this trend continues, Fulani elders will be targeted. I was present when they were cursed. People are unaware that elders have no power to intervene.”

Ahmad then reaches into his breast pocket for his tablet and plays videos showing the gory aftermath of a recent terrorist attack. In one of them, a bare-chested middle-aged man on a mattress is fanned with pieces of cartons, his trousers torn at the knees and soaked in blood. The white leather cover of the mattress and an adjacent ambulance of the same colour give off the location as a hospital. There is a splatter of blood on the cement floor. A younger victim who appears to be in a more dire condition is lifted, swiftly but carefully, off the back of a motorcycle and carried towards the entrance. There is a trail of thickened blood running down his forehead from his nose, his hair covered in dust.

The surrounding crowd are mostly young and adult men. But if you pay close attention, you can spot at least three children, likely aged between five and 10 years, standing amid the people — their faces showing innocence, curiosity, and confusion.

This is part of a series of reports supported by the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) to unmask the impact of rising insecurity in Northwest Nigeria.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter