Former Boko Haram members who have gone through the Nigerian government’s deradicalisation programme are continuously being reintegrated to their communities amidst passive rejection by locals. This is unfolding on the background of rejections on the grounds that many of them are going back to join their brethren in the bush, which indicates an underlying problem in the deradicalisation process.

As with many communities in Borno State, residents of Dikwa are also not quite comfortable with the reintegration of ex-Boko Haram militants at the present time. Except for community leaders who have been sensitised by the government and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) on the need for reintegration, many locals feel it is too early to receive ex-militants in their midst with memories of their atrocities still very fresh. They say the exercise has been imposed on them without due consultation and they cannot express grievances openly for fear of sanction from authorities.

HumAngle understands there were reported cases of rejection of “repentant Boko Haram” members in Gwoza, Bama and Gamboru Ngala but the incident in Dikwa stood out because it was openly done also by military personnel–reinforcing passive rejection by the communities.

Located strategically at the exit points to Bama, Kala Balge, Gamboru Ngala and Marte Local Government Areas of Borno, the town of Dikwa used to be the capital of ancient Kanem Borno Empire in the 18th century. About 50 km from Borno State capital, Maiduguri, it was among the major towns captured during the peak of Boko Haram’s territorial conquest in 2014. Because of its location, the insurgents designated it to be one of their major provincial capitals.

Baba Mamman, a resident of Dikwa, refers to Dikwa as a buffer zone between Sambisa Forest and the Lake Chad area. “They would come all the way from Sambisa and cross over to Lake Chad. It is the boundary between the Sambisa of Shekau and Lake Chad of Al Barnawi. Sometimes, we would see them migrating in large numbers on motorcycles and motor vehicles,” said Mamman, who now lives in Dikwa as one of the returnees. He had sought refuge in Maiduguri in 2014 as an Internally Displaced Person (IDP).

In the first quarter of 2015, the Nigerian military had recaptured many territories previously under Boko Haram control. However, in what could best be described as pseudo-dual control, a lot of the recaptured territories remained inaccessible to even the military, let alone civilians earlier driven out.

On one hand, the insurgents have retreated from these towns but still visit from time to time. On the other hand, the military did not still have a firm control over the towns as manifested by inability to ensure their safety for the return of IDPs. Dikwa, for instance, was recaptured by the Chadian military from Boko Haram and handed over to the Nigerian military in early 2015. In 2016, thousands of residents of Dikwa and other towns such as Gwoza, Bama, Gamboru, Konduga and Mafa were returned to their home towns. However, people displaced from the surrounding villages still remained in camps as the sphere of full military control over them barely transcends a few mile radius.

Residents of Dikwa town have remained in constant fear due to frequent Boko Haram infiltration into the town at night, looting food items and, sometimes, killing people. Modu Kolo’s house is located near the main Dikwa market, giving him great cause for worry whenever the sun sets. “They don’t come in the daytime. But we see their torch lights and motorcycle headlights in the night,” he observed, adding that the military and the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) were doing their best to secure the town.

The insurgency which seems to defy several strategies to be contained has continued to send Nigeria’s political and military leaders to the drawing board. One of the results of this change in strategies is the emergence of the military-backed deradicalisation programme, Operation Safe Corridor (OSC).

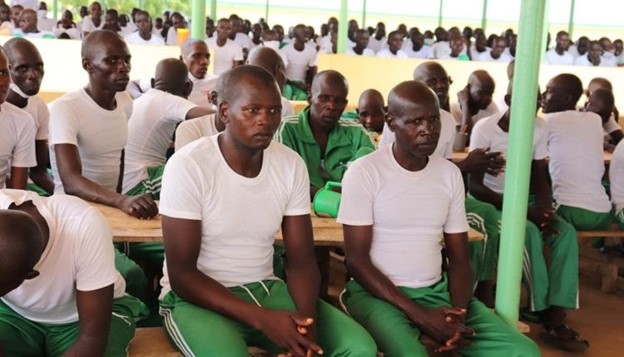

Under the programme which was initiated in 2018, Boko Haram members are given the chance to surrender to any nearest military formation. The repentant members would then undergo deradicalisation and vocational training modules in Gombe State followed by a brief sojourn at a rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri. The ex-militants are then handed over to their community leaders for an onward reunion with their families. With the vocational training and startup capital given or promised, ex-militants are expected to start a new life of responsible citizenship.

With OSC’s inauguration in 2016, Dikwa returnees have witnessed many Boko Haram militants coming out from the bush to surrender themselves. Musty, a labourer at a construction site in Dikwa said, “At times, they were kept for sometime in Dikwa before they were taken to Maiduguri. We used to see them playing football at the military unit.” He added that some that have been brought after their graduation from the past batch of OSC have not been able to unite with their families because their families “could not even be traced”.

In an unusual scenario that reflects the general sentiment, about two dozen repentant Boko Haram members arriving in Dikwa in buses were rejected by the Commanding Officer of the Dikwa Military formation, HumAngle learnt. The incident happened on Jan. 17, 2021. The ex-militants were brought from one of the Rehabilitation centers in Maiduguri on Sunday afternoon after their graduation from Gombe de-radicalisation centre. The reason for the rejection, according to locals, was that many of those earlier returned had gone back to terrorist enclaves in the bush.

Umara, as he prefers to be called to cloud his identity, is one of several youths in Dikwa town. “They have been imposing these people on us because they have power over us. To be honest, we would never feel comfortable staying with these people that have killed our people and destroyed our properties,” he told HumAngle with apparent disaffection.

Issa is another resident opposed to the return of the ex-militants. Asked where he prefers that they be taken to, he replied: “Let them take them to anywhere, but we don’t want them here. Their members are still sneaking in from the bush and troubling us.”

The ex-militants have been graduating in batches from the deradicalisation programme since 2018 and many have been reintegrated to their communities in principle as several others have not fully been received by their community members. Except for those that chose to leave their state to start a new chapter in another state, many of the repentant militants are still staying in IDP camps under the continuous security cover of military personnel and Civilian JTF for fear of stigmatisation and reprisal attacks.

“They left us here in starvation while they gave these people special treatment,” said Baba Gana in a low voice. Baba Gana is one of many IDPs residing in Dalori who are deeply dissatisfied with the “preferential treatment” offered to ex-militants while thousands of IDPs are bitten hard by starvation and poor living conditions.

Having been turned back from settling in Dikwa, when the earlier mentioned group of ex-militants arrived at the rehabilitation centre in Maiduguri, the doors were again shut to them, according to Mallam Baba, a resident living not far from the centre. “The officials and security personnel of the centre refused to admit them back. They kept waiting at the gate and were later taken away,” he said. “We don’t know where they took them to. Some are guessing that they would be taken to the other rehabilitation centre at Bulumkutu but no one is sure.”

The questions remain where were they taken to? How will this failure affect the reintegration programme in the future? And how will its recurrence be prevented?

This investigative report is part of a series of publications supported by the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund under HumAngle’s ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter