Community Feels Abandoned By Government In Conflict With Violent Herders

The absence of security agents in Ajowa-Akoko, Ondo state in southwest Nigeria, has left residents feeling abandoned and that they must defend themselves against attacks from herders – or abandon their farms.

Before he died, 48-year-old Dayo Festus had several altercations with herders, whose cattle had encroached on his farm in Ajowa-Akoko, a community in Ondo state, Southwest Nigeria.

When they arrived again on Feb. 2, 2021, he chased them away and threatened to have them arrested.

Three days later, the herders returned with more cattle. His refusal to allow the cattle to graze on his farm led to his death. His lifeless body was found bloodied with machete cuts.

Dayo’s wife witnessed his murder, Dayo’s cousin said.

Idris Alooma told HumAngle: “He went to the farm with his wife to harvest cassava but did not return home alive.”

“His wife said he was battered with machetes till he gave up. She had to hide in the bush to avoid being killed as well. You can’t go to the farm alone because of the activities of herders. Since he died, nothing has been heard about the matter, and more people have been killed on their farms.”

Dayo is survived by a 71-year-old mother, Janet Festus, two wives, and seven children.

“I am pleading with the government to assist me with the children my son left behind,” Janet told HumAngle. “He could not complete his house before he was killed. I cry every morning because the house is close to mine.”

She also wants authorities to help complete the house so that Dayo’s children can have some shelter.

Janet herself is currently nursing an arm injury she sustained during a visit to one of her farms in January.

She had gone to inspect damages to her crops by a herd of cattle. Due to the cash crunch across the country, she’s unable to travel for proper medical care.

Still traumatised by the death of his friend, Adebayo Olatunde says he abandoned his farmland in 2020.

“I used to farm along Ikare and they [herders] usually cut my cassava for their cows. Each time I confront them, they threaten to kill me and I don’t want to be killed for my children. So, I stopped going to the farm because I lost a friend of mine recently after a fight with them on his farmland.”

The violent attacks

Ajowa-Akoko, a border community with Kogi state, has recently seen an increase in insecurity.

There have been many incidents as herders, in search of land and water for their cattle, destroy residents’ farmlands.

Many herders are forced to migrate to Nigeria’s south in search of resources, as drought and desertification lead to dwindling pasture and water in the northern Sahelian region.

To address the challenges, the Federal Government, in 2019, announced a plan to create settlements across the states for herders, but this received widespread condemnation. A 10-year National Livestock Transformation Plan was then launched to reduce the movement of cattle, boost livestock production, and quell the crisis. But the problem persists.

In an atmosphere where the government is unable to perform its role of guaranteeing security or mediating in conflict, farmers have been bearing the brunt.

The conflict between the two parties has led to killings and displacements across many communities.

Many herders have also been the victims of attacks from farmers or cattle rustlers.

Even after 17 southern governors resolved to ban open grazing in their states, the fear of attacks has continued to drive farmers away from their farms.

Like other places affected by the crisis, herders who have settled down in Ajowa-Akoko for many decades say they are not the ones casting the conflict and are victims of violence too. They say the people responsible are elsewhere.

The leader of a group of herding families who live in the area, who identified himself as “Yellow”, blamed the repeated attacks in the community on foreign herders, known as ‘Bororos’.

They were the ones who crossed borders bringing with them lethal weapons, he said. It is said that these herders usually flee to new areas, making it difficult to identify and arrest them.

No police station in Ajowa

Despite hosting over 12,000 people, according to residents, Ajowa-Akoko has no functional police station to accommodate police officers amid incessant killings and kidnappings.

When HumAngle visited in February, there were no police officers in the entire community. This reporter only saw a dilapidated police building with a damaged roof and broken chairs at the counter.

Residents said there was no police officer there to attend to distress calls in times of crisis, and there had been none for three years, people said.

“In fact, abductions sometimes happen in front of the police station because the gunmen know that there are no security personnel to confront them,” one motorcyclist said.

“Even before the police station collapsed, there were only two officers at the post, making it difficult for them to handle any security complaints.”

The office of the Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps (NSCDC) in the community was empty during our investigation as well.

Residents also told HumAngle that officers of Amotekun, a “state-based law enforcement agency” created to check atrocities associated with rogue elements among herders in southwest Nigeria, are yet to significantly reduce crime in Ondo.

Ezekiel Dahunsi, a retired bishop in the community, said attention must be given to the town. “We’ve known no peace for long, and the community is spending a lot of money because of insecurity. We are tasking ourselves to provide security. The burden is much and we cannot cope any longer.”

Like Ajowa-Akoko, there are many rural communities across Nigeria without police officers and stations to report criminal offences. Meanwhile, according to a 2018 report, over 150,000 police personnel were attached to VIPs and unauthorised persons in the country.

It’s been eight years since President Muhammadu Buhari asked the police to withdraw personnel from dignitaries to allow them to tackle the rising insecurity, but nothing seems to have been achieved since then.

Community resorts to self-help

Without support from state agencies, the community fears it might soon be engulfed in a crisis. It set up the Ajowa-Akoko Strategic Development Council to find a lasting solution.

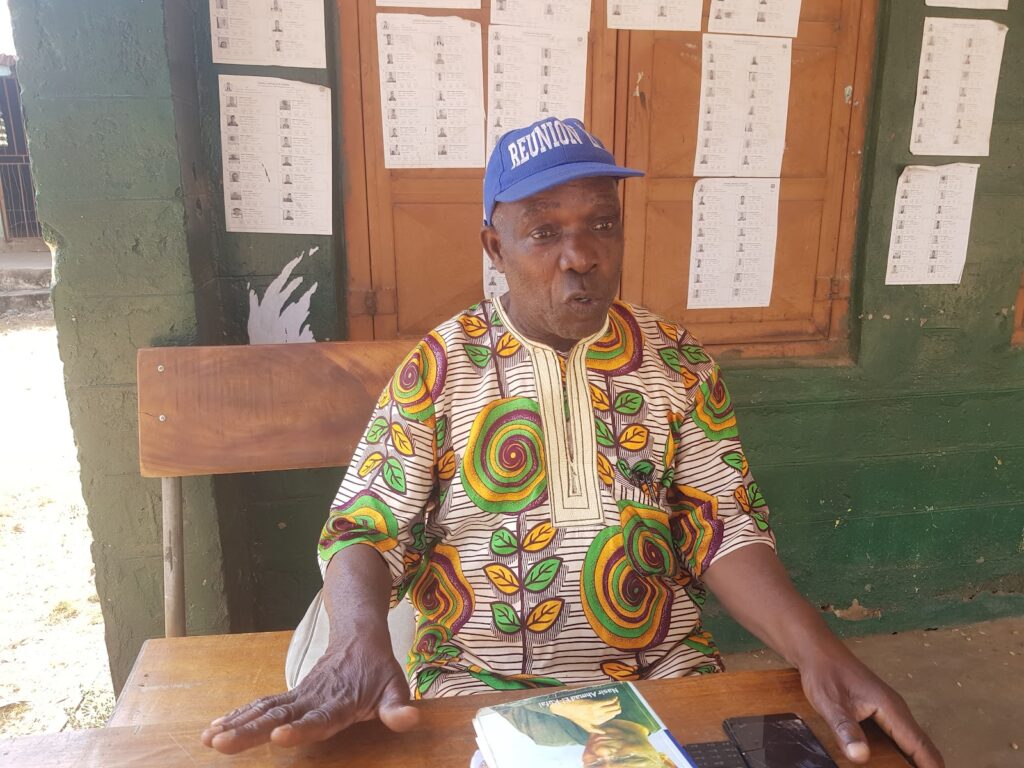

Jacob Adegoke, a member of the council, explained that the community’s location exposed it to attacks. “Our women cannot go to the farm because they get raped. They are even scared of walking on the streets because of stigma. I receive many complaints on a daily basis. The herders hide on farms and kill anyone who refuses to allow their cows to eat those farms.”

He explained that after a monarch was abducted, the council set up a vigilante group to fill the gap left by the police.

“We are paying a monthly salary to 50 security personnel to maintain peace and order. We have 20 local vigilantes who secure our people in the town and 30 hunters that provide security on our farms. We are doing this because we don’t have a single police officer in the entire Ajowa-Akoko community.

“No one goes to the farm alone, we have to go in groups because of threats. We have endured so much, but the recent incident with the monarch was embarrassing. Our people sometimes go to the farm with guns for self-defence, but it could lead to major chaos. So, we have to resort to self-help by renting a three-bedroom apartment that could be used as a police station.”

When contacted, Funmilayo Odunlami, spokesperson of Ondo State Police Command, agrees that the community is vulnerable to attack but claims officers are being deployed to the police post rented by the community.

Akin Olotu, Senior Special Assistant to Ondo State Governor on Agriculture, did not respond to enquiries when contacted.

Monarch’s abduction

On Dec 1, 2022, gunmen attacked the palace of Jimoh Omoola, the traditional ruler of Oso-Ajowa in Ajowa-Akoko. The monarch, who is also the chairman of the Ajowa Traditional Council of Obas, was kidnapped and tortured for seven days. Omoola had been vocal in defending farmers who complained about getting attacked.

His wife, Queen Jimoh Oluyemisi, said that the kidnappers arrived around 11 p.m. When occupants refused to open the door, they forced it open with gunshots.

“They shot through the door and caught me looking for my phone to call vigilantes. I told them I was sick, but they didn’t listen. They dragged me onto the floor and took the king to the bush. One of them suggested that they should leave me,” she said, crying profusely.

According to the queen, the kidnappers accused the monarch of being intolerant of herders. She said her husband had insisted in the past that herders who broke rules in his community face stiff fines.

“My husband usually made them pay ‘through the nose’ anytime they got caught. When taking my husband away, they took my phone with them. It was what they used to reach the family members three days later.”

They demanded a ₦100 million ransom, but Queen Jimoh proposed ₦500,000. Not pleased with the amount, Oba Jimoh was tortured with burning firewood in the bush.

As part of efforts to ensure the monarch’s safety, the community started collecting daily contributions from different households and from Ajowa-Akoko indigenes abroad.

“Seven days later, the donation got to ₦6 million ($13,030). My son and his friend reached out to them and the kidnappers asked that the ransom be brought to Lokoja in Kogi state,” said Oluyemisi.

“They accepted the money and freed him on Dec. 8. He was then taken to the hospital, where he spent over a week for medical care because he had injuries all over his body.”

Three months after his ordeal, he is still being treated for his injuries, she said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter