Caught In The Line Of Fire: Health Workers Not Spared In Nigeria’s Unending Conflict

Over the years, attacks on healthcare workers and facilities in Nigeria’s North West by terrorists have been on the rise, making an already fragile health system even worse.

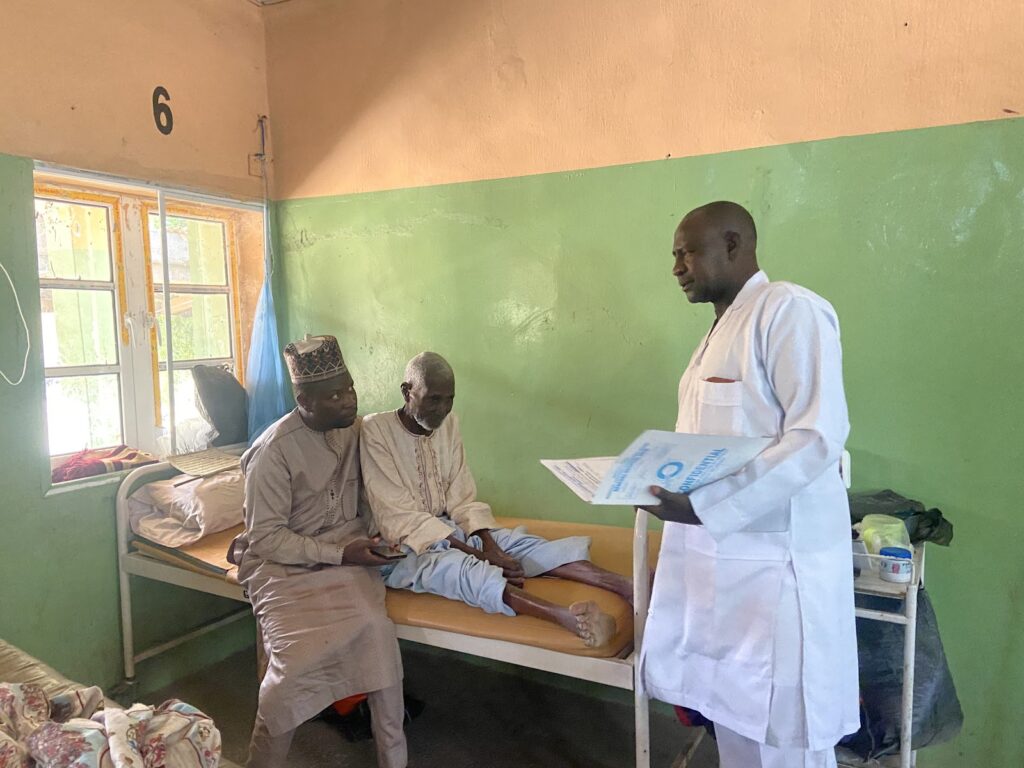

There is a way Yinusa Bello speaks that brightens patients in the male ward of the General Hospital in Jibia. His footsteps were unhurried as he walked calmly into the ward, looking right and left and smiling at each turn. He paused halfway to examine a young man and stopped again at the tail end of the ward to check the file he was holding. The patient, an old man presumably in his late sixties, nodded while Bello scribbled something illegible on the chart.

Soon, he picked his pace and moved to the next bed. It had become a habit for the 53-year-old. A few minutes later, he was back to the broken plastic chair at the entrance of the ward, where some patients’ relatives were waiting for him.

“This is my seventeenth year as a nurse,” he mused with pride. “It has always been my dream right from childhood: to be able to help and assist others when they are ill.”

Over a year ago, that passion would almost get him killed.

He had spent 17 long days in the thick of Jabiyawa forest tied firmly in both wrists and ankles and deprived of food and water following his abduction by terrorists.

One Monday in September 2022, Bello woke up refreshed for the new week. He had spent the weekend with his wife in Jibia and was ready to resume duty at the Zandam Health Clinic in the Mazanya area of Katsina. As the only health worker in the border village, there was no time to waste. He had backlogs of files and patients he needed to see. Although he had two young men from among the townspeople who assisted him, there was literally nothing they could do in his absence.

He hopped on his rickety bike, his lunch and a box strapped to the back, and hit the road. This was his routine every weekend since he was posted to the village. Along the way, at the intersection of Jabiyawa village towards Zandam, he was stopped by terrorists who had laid siege on the road. He froze in fear. The terror he had heard of, mostly from patients who came in for treatment and relatives, had caught up with him, too. Before he knew it, he had a hood over his head and was led away into the forest.

“It’s the most torturous moment of my life. They tied my hands and legs and spent nine days before they even offered me water to drink,” Bello told HumAngle.

That was nothing compared to the constant whipping he received, which still affects him to date as he finds it hard to lie down in bed properly because of pain in his back.

Before long, they reached out to his family, asking for ₦1.3 million ($1,445) in ransom. It’s way above what the family earned. They started reaching out to friends and relatives from whom they borrowed to secure his release. But the coast isn’t entirely clear for the family, at least not yet, because of the debts. They had to obtain a bank loan to pay everyone they borrowed from. Every month since his release, the sum of ₦42,000 gets deducted from his meagre salary as repayment. So far, he has paid for 15 months. He has 26 more to go.

Bello will complete the repayment plan just four months away from his retirement in July 2026.

“Honestly, there is so much concern because my salary is not even enough at all once the bank deducts their own money. I do not wish for anybody to experience what I went through in the hands of those people and the situation we now find ourselves in,” said the father of six.

Terrorists have prowled North West Nigeria for many years now. They’ve masterminded a million-dollar kidnap-for-ransom industry across the region. The terrorists also extort and attack villages, kill civilians, sexually assault women, and rustle cattle. They enjoy a certain level of influence, so much so that they settle local disputes, impose levies on communities, and even run illegal mining operations.

There are thousands of them across large swathes of the region’s ungoverned spaces, from where they launch attacks, stockpile weapons, and hold abductees like Bello.

Since the conflict escalated about 12 years ago, at least 12,000 people have been killed and hundreds of thousands displaced across the northwestern states of Sokoto, Kebbi, Zamfara, Katsina, Kaduna, and parts of the North-Central region.

Unfortunately, hospitals and healthcare workers are not immune from the violent attacks. According to the Katsina State chapter of the Medical and Health Workers Union of Nigeria (MHWUN), about 100 healthcare workers have been kidnapped and 20 killed so far across the eight frontline areas in what appears to be a clear violation of international humanitarian law.

‘Perilous medicine’

Shamsu Yusuf, 41, sat on a wooden chair in his home in Jibia. Hunched forward, his chin resting on his arm, he spent 30 days in captivity in the Barawa forest area in Katsina after terrorists attacked Nomadic Clinic, Tsamben Tsauni, in the same axis.

Yusuf was in the consultation room attending to patients when the roars of motorbikes enveloped the health centre. In the region, terrorists mostly announced their presence by riding on bikes when raiding villages. So, when they heard the deafening noise and saw a gust of dust hovering over their heads, everyone knew instantly they had to scamper for their lives. But it was too late.

The terrorists had marched into the clinic.

“They surrounded the clinic while some of them entered and started asking where the health workers were. I came out of the consultation room, and they grabbed me, asking where the money was. I told them we had no money in the clinic. They searched everywhere but didn’t find any money.”

Yusuf thought that was all they came for. But just when the invaders, loyal to the notorious terror kingpin Sani Dangote, were retreating, one of them held him in the neck and matched him outside. Five other people were taken alongside him.

“They took six of us and told us to get on their motorcycles. When we got to a point in the middle of the forest, they stopped and took off our clothes to blindfold us,” he narrated.

After some minutes or hours — he could not really tell — they got to the terrorists’ camp. Like Bello, his legs and hands were also tied and tethered to a tree. After a night, they untied his hands and asked him to call his family and inform them he had been taken, and the ransom was ₦4 million ($4,448). He was devastated. The only way he could raise such an amount was to sell his properties and borrow some money from extended family members.

He spent most part of the day tortured and passed the nights in the cold. The family was eventually able to club together ₦2 million and begged the terrorists to accept it. “Since the incident, I find it hard to sleep at night. Any small noise startles me. The situation we find ourselves in is quite pathetic. No one is spared from the atrocities of these guys,” Bello said, heaving a long, weary sigh.

Following his release, Yusuf immediately processed his redeployment to the Magama health clinic in Jibia, where he currently works.

Several states have failed to uphold global commitments intended to safeguard healthcare workers in conflict areas despite being signatories to provisions like the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2286, which condemns violence and threats against medical personnel and charges member states to protect healthcare from the violence of war.

Between 2016 and 2020, there were 4,094 reported attacks and threats against healthcare in conflict areas across the world, according to Safeguarding Health In Conflict Coalition, a group of more than three dozen human rights and humanitarian organisations working in conflict zones.

During this period, at least 1,524 health workers were injured, 681 were killed, and 401 were kidnapped. There were over 978 incidents where health facilities were either totally destroyed or damaged.

In Nigeria’s North West, these relentless attacks are beginning to shrink the capacity of the country’s health system to cater for those in need, especially in rural villages. Residents of rural communities in the country, despite making up about one-half of the population, only have access to an estimated 12 per cent and 19 per cent of the total number of physicians and nurses, respectively. It’s only going to get worse as the attacks continue with brazen impunity.

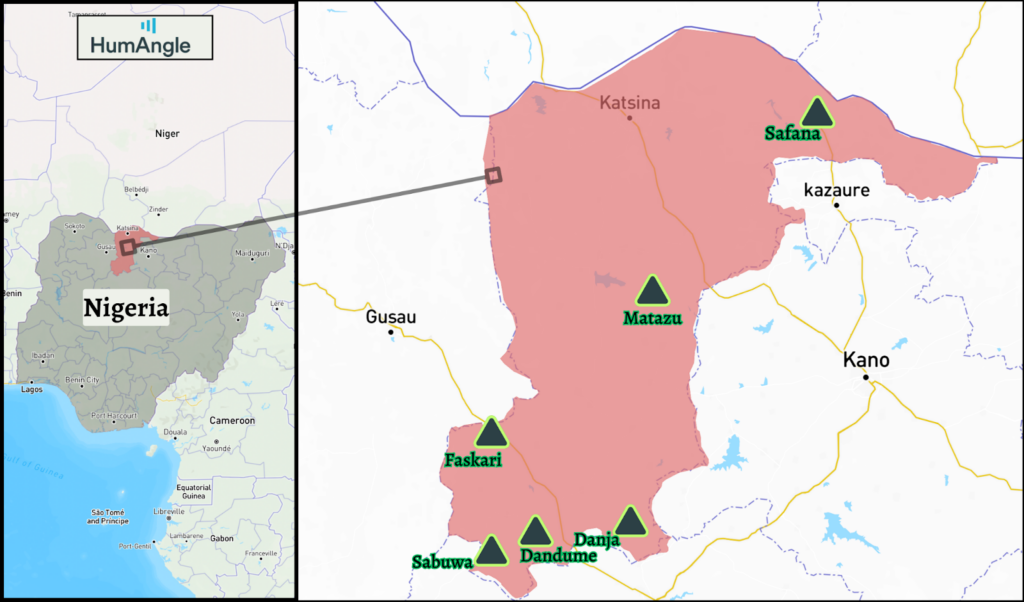

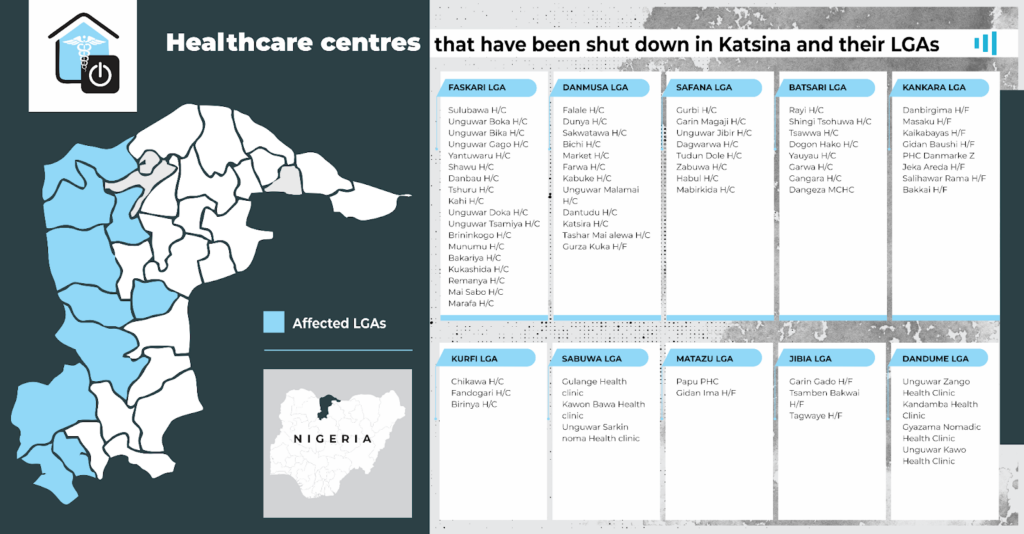

Because of the raging conflict in Katsina, for example, HumAngle gathered that there are no healthcare workers and that no fewer than 69 health facilities have been shut down across Faskari, Danmusa, Safana, Batsari, Kankara, Kurfi, Sabuwa, Jibia, Matazu and Dandume local government areas. Sadly, this leaves locals in these areas without access to medical care.

For instance, residents of Zandam, where Bello previously worked before his redeployment to the General Hospital, travel approximately 10 kilometres to seek medical care in Jibia. Apart from the financial strain it puts on an already impoverished population, they face the dread of being kidnapped along the risky highway.

So, many sit it out, except it’s a matter trapped between life and death.

Not only that. Across Faskari, Dandume, Sabuwa, Danja, Safana, and Matazu local government areas, there are no medical doctors to cater for the needs of an estimated population of 1.6 million people — a situation experts described as not only catastrophic but a national emergency.

The country already doesn’t have enough workforce to meet the needs of the growing population. According to the World Health Organisation, Nigeria has a ratio of four doctors per 10,000 people. This is far below WHO’s recommended doctor-to-patient ratio of 1:500.

“These areas had doctors before. They all left because of the issue of banditry. It is disheartening. We have some of our General Hospitals with one doctor and facilities like the primary healthcare centres that no longer have any doctors. We are between the devil and the deep blue sea,” Adamu Saminu, the state chairman of the Nigeria Medical Association, told HumAngle.

“I can say for a fact that within the last year and a half, over 200 doctors left their jobs here in Katsina for other places because of the issue of insecurity and the economic realities of the country. Some of us that are still here are doing so out of patriotism even when we practise under fear.”

Attacks on health workers and facilities have a very profound impact on the quality of healthcare, said Kemisola Agbaoye, Director of Programmes at Nigeria Health Watch.

“It overwhelms and significantly impacts the resilience of the health system to accommodate the needs of the local communities, which historically do not have sufficient workers compared to the urban areas. Apart from the fact that healthcare workers tend to migrate to safer areas, it also disrupts the existing supply chain, usually a system that makes sure that medical supplies, vaccines, drugs get to the end users,” she said.

This, together with the neglect and underfunding of health facilities, makes it difficult for the local communities to access quality healthcare.

One tragedy too many

Nigeria has a struggling health system and some of the world’s worst health statistics. With an average life expectancy of 54, one of the lowest globally, the country accounts for 20 per cent of global maternal mortality. It has also been in long-running industrial actions with pressure groups in the health sector over poor pay and inadequate facilities.

Amidst this, there’s a mass exodus of doctors that continues to put a strain on those on the ground. At least an estimated 2,000 Nigerian doctors emigrate yearly to countries like the United States and the United Kingdom.

In the North West, as healthcare workers leave their jobs to dodge bullets and health facilities shut down in hotspot areas, health facilities and workers in safer towns are under immense pressure as locals trudge to these facilities for their needs.

It’s a little after 4 p.m. A ray of sunlight cast a faint shadow on the cracked wall of a square-shaped office block at the General Hospital, Batsari. Older men and women waltzed in. Inside, Umar Saleh’s office was flung open and patients wearily queued for their turn. Saleh looked exhausted and stone-faced. He adjusted his glasses and took one of the files sprawled across the table, scanning a few pages, before calling in patient Alhaji Amadu.

Three years ago, when Saleh was posted to Batsari, he drowned in his own thoughts for several days. Batsari has seen a resurgence in killings and kidnappings over the past few years. And it was definitely not a path he was willing to take.

“I was not happy. I felt so bad that I thought about quitting the job.” He cupped his hands together. “But at the same time, I got a lot of advice from senior colleagues who urged me to rise up to the challenge.”

Saleh gathered himself and took the challenge.

“When I came here, I was not the only one. I met a doctor. When she was here, things were a bit less stressful because we used to alternate between theatre cases and consultations,” he recalled, but the colleague would soon leave, creating a gap he has been unable to fill.

Saleh called Alhaji Amadu to be sure he was still around and okay. When he saw that the 60-year-old, helped by a young boy, was staring up at the leaky ceiling and jaded, he quickly dropped the pen in his left hand and rushed to help the man to the chair in his office.

“Being the only one is tiring. I have to consult patients and also oversee things in the theatre while staying here from Monday to Friday,” he continued after returning to his seat. “I’m always on call; look at the time, and they are still adding more cards. I don’t even have a closing hour. I close when there are no cards or patients to attend to. If I should go on sick leave for a day or two, they would start referring patients elsewhere.”

Many health workers in the region are overworked and stressed as a result of the raging conflict. HumAngle presented their situation to a Clinical Psychologist, Hassan Tajudeen. He pointed out that the workload of the health workers can be overwhelming due to the “unending demands for their services” in the areas they practise.

The “seemingly unending exposure to stressors,” he added, “can lead to fatigue, burnout, anxiety and depression. Security concerns and limited resources are also factors that can add to the psychological impacts on the health workers in conflict zones.”

But Saleh believes, like the biblical story of the shepherd and the sheep, that he needs to always show up for the local communities.

“I’ve gotten so used to the people. And the trust is there. I’m glad that since I got here, we’ve not been referring patients for some of these minor cases. But we need enough manpower. If we’re like three or four here and with the nurses, these people will have enough hands to look after them.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter