Burnt Armoured Vehicles and Other War Relics Haunt Borno Communities

Burned armoured vehicles, rusting tanks, and fragments of military equipment stand as silent reminders of the fierce battles between the Nigerian Army and Boko Haram insurgents. The constant presence of these war relics carries a psychological toll too much to bear for residents.

Adamu Abdulsalam is a civil servant and small-scale farmer who regularly travels from Gwoza town to Kirawa in Borno State, northeastern Nigeria. The 38-year-old often finds it hard to escape the emotional weight of coming across the remnants of war along these routes.

“Honestly, I am always frightened by the burnt vehicles I see whenever I travel,” he said.

Adamu’s town, Kirawa, was attacked in 2014 by Boko Haram insurgents in their quest to establish an ‘Islamic state’. The town, like many others in Borno State, has since been displaced until recently, in 2022, when the state government resettled the community.

“One particular sight that haunts me is the Nigerian Army armoured vehicle stationed at the entrance of Kirawa, burnt during the 2014 attack,” he said. “That attack displaced the entire town, and I was among those who fled on foot, enduring precarious conditions as a displaced family in host communities and Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps in Maiduguri.”

Adamu explained that these relics trigger flashbacks to the horrific events of the past. “Every time I see those vehicles, it feels like the battle is still ongoing. It gives me memory attacks and makes me regret coming back to the town. One question always lingers in my mind: if such vehicles couldn’t withstand the attack, what chance do I have?”

The abandoned military relics scattered across Borno State, once formidable instruments of defence and destruction in the fight against insurgency, now serve as haunting reminders of past violence. For many residents, especially frequent travellers like Timothy Tuksa, these remnants are not just physical debris but emotional triggers.

“Seeing these remnants makes me feel like an attack could happen at any moment,” said Tuksa, who often travels on the Maiduguri-Gwoza road. “The fact that the government has not cleared these vehicles suggests to us civilians that the war isn’t over. It’s unsettling, and I believe immediate action is needed to remove them.”

When HumAngle embarked on several trips on the sprawling cultivated lands through the rural communities along Maiduguri – Gwoza road in Borno, it was impossible to ignore the presence of incinerated armoured vehicles and other military equipment left in the open.

These relics mark the sites of intense clashes between Boko Haram insurgents and the Nigerian military, battles that claimed lives, uprooted families, and left entire towns in ruins.

For Umar Usman, a 31-year-old farmer from Pulka, every time he passes by the charred remains of vehicles or sees the debris of war, he is transported back to the harrowing memories of the conflict that ravaged his hometown.

“It’s like the war never really left us,” he told HumAngle. “Whenever I see those burnt tanks or wreckage left behind by Boko Haram and the military, the memories come flooding back. It’s like the war never really left us.”

According to Umar, the war caused death and the disappearance of at least three of his family members. The most disturbing memory for Umar is the death of his uncle, who was killed by a stray bullet during a fierce confrontation between Boko Haram insurgents and the Nigerian Army in Pulka. “I remember that day clearly,” he recounted. “We were all inside the house, thinking we were safe. But suddenly, a bullet came through the wall and struck my uncle. He died right there, in front of all of us.”

The sight of relics stirs this pain anew, making it difficult for Umar to move on. “My uncle was not the only one; many in our community lost their lives or were displaced. These relics bring back those dark days and the grief we try so hard to forget,” he added.

Umar believes clearing the relics from Pulka and other affected areas is essential for rebuilding the community and for individuals like him to find peace. “We need to see a future without these reminders of war. Only then can we truly begin to heal,” he added.

Since the Boko Haram insurgency erupted in 2009, more than 30,000 people have been killed, and over two million people were displaced by 2022, according to the United Nations Development ProgramAs of March 2024, more than 50,000 members of the terrorist group have surrendered to authorities through Operation Safe Corridor, a government-led programme in northeastern Nigeria aimed at deradicalising and reintegrating members of the group who were willing to give up the extreme ideology.

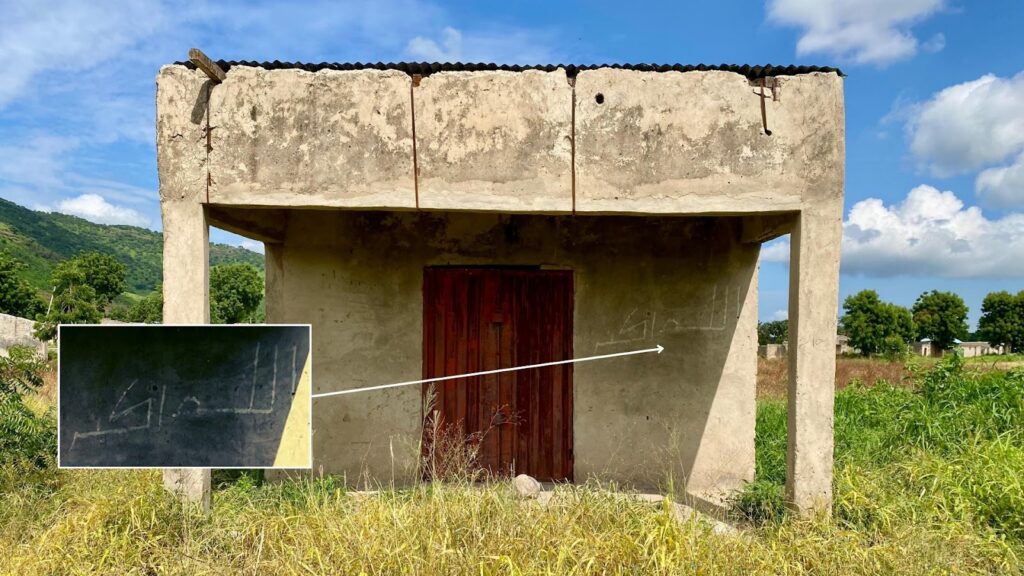

There are also destroyed buildings marked with ominous writings left behind by Boko Haram insurgents. These serve as additional, haunting reminders of the violence that once ravaged the region and continue to burden communities attempting to rebuild.

“These burnt-down domestic vehicles are heartbreaking,” said Abubakar Musa, a community elder in Bama. “Each one tells the story of people fleeing or caught in the crossfire. It is like walking through a graveyard every time we see them.”

In Gwoza, over six disturbing war relics are scattered across various locations, including Warebe, Pulka, Government Secondary School Gwoza, and Anguwan Sarki, according to local sources.

Gwoza has witnessed devastating episodes of violence, such as the recent suicide attack in July 2024, which claimed at least 32 persons, and the deadly Gwoza massacre in June 2014, where 400 people were killed.

Scars on the walls, fear and trauma

Entire neighbourhoods in once-thriving towns like Kirawa, resettled in 2022, are filled with collapsed homes, roofs caved in, walls charred black, and debris strewn across the streets. These buildings bear the undeniable scars of military battle. Families who once lived there are either displaced or struggling to return while grappling with the emotional trauma of seeing their homes reduced to ruins.

Adding to their distress is the haunting graffiti scrawled across surviving walls and buildings, bearing chilling messages depicting the presence of once-occupied territory. For residents, these writings are disturbing reminders of the terror that once ruled their communities.

“When we returned to our village, the first thing we saw were the walls of our neighbour’s house carrying the writings of Boko Haram. It’s as though their presence still lingers, even though they are no longer here,” Musa Ahmed, a resident of Kirawa, said.

He added, “When you see those burnt cars or those writings, it feels like Boko Haram could return at any moment. We need these things cleared so we can feel safe again.”

As much as it showcases the tenacity and ferocious battle carried out between the Nigerian Army and Boko Haram, these relics and footprints of terrorism need to be taken out from the faces of people who are rebuilding their lives after so much was lost, experts say.

Musa Abdullahi, a sociology professor at the University of Maiduguri, explained the implications to HumAngle. “Every event associated with the insurgency, like the killings, destroyed buildings, and weapons, has left behind trauma, especially for those who faced the conflict directly. These reminders trigger retrospective throwbacks, disturbing victims psychologically and sometimes pushing them into depression,” he explained.

According to him, the impact varies among individuals. For some, the clearance of war relics in urban centres like Maiduguri has helped them move forward. However, the trauma persists in rural areas, where relics remain prevalent. “In these resettled areas, the reminders of war like burnt down buildings and vehicles, military checkpoints, are everywhere, and for older residents already struggling with health issues like high blood pressure, these triggers can lead to severe depression and other mental health crises,” Prof. Abdullahi added.

The sociologist also noted that beyond psychological effects, the war relics have also disrupted livelihoods, particularly for farmers who face “phobia and depression” due to the security measures required to access their farmlands.

The lingering threat of attacks forces farmers to operate under strict timelines set by military checkpoints. “The fear of the unknown, combined with warnings from the military that they are on their own when they go to the farm, significantly affects agricultural productivity,” he explained.

Prof. Abdullahi also highlighted the frustration caused by heavy military presence along major roads. “Despite announcements that roads are accessible and secure, the numerous checkpoints remind people that the war is not truly over,” he said.

Abandoned settlements along these routes are especially distressing for travellers. He added, “Seeing deserted and ruined communities is the most disturbing memory for many.”

Taking a toll on the environment

The environmental consequences of abandoned military tanks and armoured vehicles extend beyond their visible presence. According to Yadomah Mandara, an environmentalist and Founder of the Bukar Mandara Foundation, a local non-profit assisting victims of the insurgency, the long-term effects of these relics are deeply concerning.

“These vehicles contain a cocktail of chemicals and hazardous substances that can easily seep into the soil or contaminate water bodies, causing devastating environmental damage,” Mandara explained. She added that the corrosive metals and leaking fuels from the relics are particularly alarming. Over time, these substances infiltrate the ecosystem, degrading soil fertility and polluting nearby rivers and streams, a lifeline for agriculture and daily living in affected communities.

Additionally, Mandara warned of the potential for these relics to carry unexploded explosives, which pose significant risks to both human lives and the environment.

Mandara advocates for the responsible recycling of abandoned military hardware to address these risks. She emphasised the potential benefits of repurposing the materials from these vehicles into valuable products like construction materials or industrial components.

“Recycling these vehicles is a crucial step towards preserving our ecosystem for future generations. By transforming this waste into something useful, we not only reduce environmental harm but also create economic opportunities for the local community,” she said.

Prof. Abdullahi stressed the importance of addressing not just the physical remnants like burnt military vehicles but also the broader consequences, including abandoned settlements and the presence of military infrastructure. “These sights reinforce the memory of the war, and their removal could help people regain a sense of normalcy,” he noted.

Adamu Abdulsalam, a civil servant from northeastern Nigeria, recounts the haunting sights of abandoned military relics along his travel routes, remnants of the Boko Haram insurgency that have deeply impacted communities in Borno State.

The leftover vehicles and destroyed architecture serve as emotional triggers for returning residents, including frequent travelers like Timothy Tuksa, who sees these as signs that the conflict hasn't truly ended. The widespread presence of these relics has psychological implications, disrupting the process of healing and normalcy for those affected by the conflict.

Residents like Umar Usman, who lost family members during the conflict, find it difficult to move on as these reminders keep the memories of violence alive. The conflict, which began in 2009, has killed over 30,000 people and displaced millions.

Environmental concerns also arise from these abandoned war materials, which contain potentially hazardous substances that could contaminate soil and water sources. Experts advocate for the removal and recycling of these war remnants to reduce their psychological and environmental damage and aid in the region's recovery efforts.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter