Book Review: Hidden Roles Mediators Played In Securing Chibok Girls’ Release

The authors say proceeds from the book will be used to fund educational needs in Chibok, especially for the families of survivors.

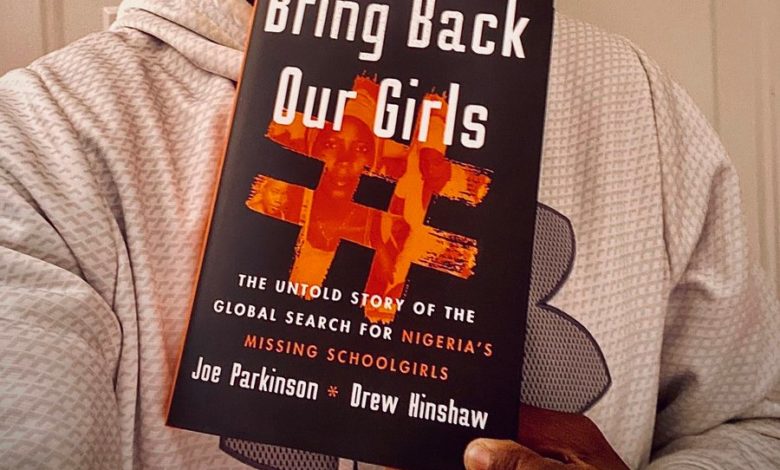

When terrorists successfully abduct a group of civilians and hold them hostage for a long time, public discussions often suggest that the road to their rescue is straightforward, typically involving the swift deployment of military muscle. But as Joe Parkinson and Drew Hinshaw show us in their recently released book, Bring Back Our Girls: The Untold Story of the Global Search for Nigeria’s Missing Schoolgirls, this is far from what truly happens.

In 414 rich and riveting pages, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) writers share details about the April 2014 Boko Haram abduction of nearly 300 Chibok schoolgirls in Borno, Northeast Nigeria, and the struggle for their release.

Leafing through those pages, one will come to understand the significance of that event and the subsequent #BringBackOurGirls (BBOG) campaign, not just for the small community of Chibok and the kidnapped girls, but also for the insurgent group’s fluctuating stamina, the change in Nigeria’s central leadership, and the general security landscape in the Lake Chad region.

The authors show how forceful approaches to rescue can backfire and how making victims of abduction famous through social advocacy may not always give desired outcomes.

Importantly, the book brings to the world’s attention the covert roles played by conflict mediators, Nigerians and non-Nigerians, who risked their lives to bring the warring parties to the table of compromise while prioritising the safety of the abducted girls.

These mediators, the authors noted in the introductory pages, included Qur’anic scholar Tijani Ferobe, Swiss diplomat Pascal Holliger, terrorism analyst Fulan Nasrullah, then freelance journalist Ahmad Salkida, former Boko Haram disciple Tahir Umar, and lawyer Zannah Mustapha.

Many of them worked closely with senior government officials behind the scenes to get the Chibok schoolgirls released. But it was not easy navigating between government bureaucracy, the ego of a sovereign nation, inter-agency rivalry, the unpredictable narcissism of a terror kingpin, among a host of other factors. The intrigues that came with paddling through those bumpy waters are vividly spelt out in Parkinson and Hinshaw’s book.

“Speculations should not becloud the fact that there are many well-meaning patriots including myself that are working quietly day and night for peace,” Salkida, now CEO and Editor-in-Chief of HumAngle Media, had tweeted on May 26, 2014.

Three days later, he posted another cryptic message on the microblogging platform: “It’s enough challenge to be Nigerian, difficult to commit to serving Nigeria like the soldiers on the frontlines and extremely distressing to love Nigeria.” His tone was that of a man who had resigned to fate after losing a protracted battle.

Unknown to a lot of people, at this time, Salkida was travelling between countries at the behest of the Nigerian government, leaving his job and family to leverage on his contacts within the insurgent group and strike a deal that would favour the girls. The BBOG campaign had shaken the internet and international community. Prominent figures, including those at the White House and top echelons of other foreign governments, were putting pressure on the Goodluck Jonathan-led administration to get the schoolgirls out of captivity.

In the first week of May 2014, Salkida was in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on a self-exile after facing threats to his life in Nigeria because of his reporting. Shortly afterwards, he was on a plane back home. At the statehouse in Abuja, former President Jonathan placed his hand on Salkida’s shoulder and assured him of his support.

After a back-breaking trip to Boko Haram’s forest camp and long hours of back-and-forth between the mediator and the insurgents, a swap deal was finally scheduled for May 18. However, at the eleventh hour, with Salkida already jetting towards the location of the exchange, the Nigerian government called off the deal. Appreciating that his life was suddenly at risk, the alarmed journalist got on the fastest flight back to the UAE with his family. Days later, he would unlock his smartphone and tweet about how difficult it was to serve or love Nigeria.

Salkida’s job was not done. The following year, after Muhammadu Buhari was elected president of Nigeria, he returned to Nigeria to make a second bold attempt at getting the girls to freedom. This also was not successful, but this time it was because the militants grew greedy and suddenly started renegotiating the terms of the deal. Again, Salkida had to flee the country.

Back with his family, he announced through his Twitter account: “I’m glad for what I tried to accomplish and for what I’ve done silently. There is no contribution more rewarding than one that goes unnoticed.”

It was Zannah Mustapha’s collaboration with the Swiss government’s Dialogue Facilitation Team that would eventually yield tangible results, Parkinson and Hinshaw reveal in their book. Thanks to Pascal Holliger’s recommendation, Mustapha had been trained by the Swiss government’s Human Security Division on the art of peacemaking and mediation.

In 2016, military advances had weakened Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau’s grip over his followers, and driven a wedge between the ranks. There was a severe food shortage in the terrorist camps. Shekau was desperate for more resources and control, and the Chibok girls, his prized captives, seemed like the perfect bargaining chip.

Zannah, like Salkida, had had encounters with Shekau that preceded the group’s 2009 uprising and could be trusted by both the state and non-state actors. Twenty-one (21) girls, yet to be forcefully married to militants, were freed in Oct. 2016. This was with the help of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which provided logistical support. Zannah was at the exchange ground to receive the girls, a moment he had worked tirelessly to witness for years.

About seven months later, amid fresh obstacles, a bigger batch of 82 girls was released by Boko Haram. The deal involved both a prisoner swap and an exchange of money.

Since this deal, there has been none other involving the Chibok girls though over a hundred are still unaccounted for. It is feared that the majority of them have been married off to various Boko Haram members or have lost their lives to different events. However, every year on the anniversary of the abduction, Nigeria’s president, almost mechanistically, renews hopes of reuniting the remaining schoolgirls with their families.

“But those talks made little progress, and today officials quietly doubt that there will be another major release,” note Parkinson and Hinshaw in their postscript.

The authors wonder if the bid to release the children could have ended differently given a different set of circumstances.

“Nearly all of the students would have been released, mediators broadly agree, if Nigeria’s feuding intelligence and defense agencies hadn’t called off so many of the early hostage swaps,” they answer. “There is also the troubling counterfactual that more might have been able to escape, as thousands of Boko Haram victims have, if social media had not elevated them into an invaluable bartering chip, guarded so closely for such a long time.”

Nevertheless, the story of the over one hundred schoolgirls who made it back to the lives stolen from them by Boko Haram cannot be told without a mention of the “tireless efforts of unsung Nigerians who put their lives at risk, and in some cases, continue to do so as they try to bring their country peace”.

“Those individuals, referred to throughout this book, and others not mentioned, may never receive their due credit,” the authors add.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

One Comment