Basic Education Crisis May Feed Terrorism In North-central Nigeria

Inadequate basic education in insecure regions of Nigeria, such as the North-central, are potentially harmful as they make children vulnerable to anti-school ideologies propagated by terrorists.

The divorce papers arrived on a Wednesday. As he made his way through the shanty area his rented apartment was located at, children —oblivious, like him, of how his life was about to change — hailed Malam Idris* from both sides of the road, most of them dirty or hardly dressed, some in old, neat clothes. “Uncle! Uncle!”

They were pupils of a government-owned primary school in Chanchaga, Minna, where he taught.

His passion for teaching ran deep and reflected in the way he interacted with the pupils who loved him for his dedication. But perhaps it was also gratitude. “They, just like their parents, know that I am working with little to no pay,” he tells HumAngle. “And they appreciate it.”

But appreciation couldn’t fund his marriage.

His marriage began to crack when he moved in 2018 with his wife from the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), Abuja to Minna, Niger State in North-central Nigeria. He had later secured an appointment as a primary school teacher with his degree in Biology education.

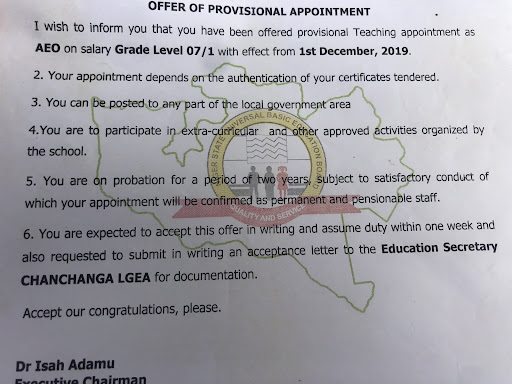

The first injustice and irregularity he noticed was that he was placed on Grade Level 7/1, instead of the level 8 that was prescribed for degree holders by the Salary scale.

The second injustice was that he worked for five months, from Dec. 2019 to April 2020, without pay. When the pay eventually came in May, it was 34,000 naira, a far cry from the 43,000 naira he was supposed to get. The next pay came two months later, and was an inexplicable 32,000 naira. The rest of his salaries came erratically; he never quite knew when or if it would arrive, but he could count on the fact that when it did, it would have been reduced by a thousand or two naira. Sometimes, it got halved. Many times, he was paid in percentile, with the government claiming that it could not pay in full. His bank statements, perused by HumAngle, show that he has received as low as N11,000 in some months.

It was never enough to care for his wife, who was still unemployed at the time, and their few months old son when he eventually arrived. They bickered endlessly about the lack of money, especially at his refusal to resign and find another job. It heightened during the COVID-19 lockdown when they were forced to stay at home.

“That time, I couldn’t go out to hustle and get small money, because of the lockdown. And there was no COVID-19 relief too,” he recalls.

Eventually, she opted out of the marriage. “It was understandable,” he says. “Things were so bad that we couldn’t eat regularly. And I refused to resign.” His refusal to resign meant he was spending precious time on something that did not fetch him any monetary returns— time he could have spent working other jobs.

Malam Idris is one of the primary school teachers in Niger State whose salaries have been butchered and many times stopped inexplicably by the government, and who have suffered severe, real life consequences as a result. This neglect has proved symptomatic of the general neglect of primary school education in Nigeria, as the same treatment is not obtainable in secondary schools. The situation is similar in primary schools in some other states as shown by a recent report.

What it means for pupils

Apart from the personal ways in which this neglect affects the teachers’ lives, it also interacts with the dilapidated school buildings and absence of teaching and learning materials, to affect the quality of education.

The overspill of this is an increased number of primary school dropouts, and an extremely low enrollment frequency into Junior secondary school in the state. It also translates to increased workload for secondary school teachers, who must now try to fill the educational gap in the lives of students who are products of the nonworking primary school system. This, ultimately, creates a poor secondary education as well. This deterioration in the quality of primary school education, particularly in low income communities and rural areas, affects the ability of children to compete for spaces in good public secondary schools, which in turn hinders their access to scarce tertiary education and job opportunities. This situation further disincentives education.

“Sometimes, I see some of my former pupils roaming about the streets during school hours. They don’t proceed to junior secondary school anymore because the foundation is not there. Teachers are not empowered or compensated enough to teach, so they often do not go to work. Even I want to quit,” Malam Idris tells HumAngle. “And if this is happening in Minna, the capital city, it makes you wonder what is going on in the suburban areas,” he laments, his forehead creased in pain and frustration.

According to a report by Dataphyte, 3.7 million children don’t complete primary school education. They drop out. This data also highlights an important element that breeds inequality and associated security and economic risks.

According to data published in 2018 by the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC), though primary school has the highest rate of enrollment at 27.9 million as against the 7.2 million at secondary school, only 86.81 per cent of primary school entrants complete the school. North-central Nigeria, where Niger State is situated, was reported to have the least and below average completion rate in the country. This corroborates Malam Idris’s claim. Niger State also has a low number of teachers, according to data, recording 14,650 teachers in junior secondary school in 2018/2019. For context, the state with the highest number of teachers had 153, 305.

Teachers are also underqualified

The same report shows that about 37.6 per cent of teachers at primary school levels in Nigeria are unqualified. Again, North-central Nigeria accounts for the most significant part of this figure.

The Niger State Salary Management Committee 2020, set up by the government to investigate and verify records of all civil servants in the state over the course of three months, found that many teachers were unqualified. Its investigation involved inviting all civil servants in the state over for physical verification.

Documents obtained by HumAngle show that over 100 teachers were found to be in possession of fake educational qualifications —such as forged NCE certificates and even in some cases, bachelor’s degree certificates. These certificates were sometimes their entry qualifications. The poor working conditions and government interest in primary school education translates in the quality of teachers; in some cases, the process of employment is ridden with corruption.

The educational system seems to be facing a real crisis.

What it means for insecurity

One of the major premises of terrorist groups, particularly Boko Haram, is the criminalisation of formal education. Boko Haram directly translates to mean Western education is forbidden; the group exists to threaten the legitimacy of, and criminalise conventional education. Similarly, faulty education systems increase the fragility of communities and their vulnerability to recruitment by criminal groups.

Past and recent attacks — especially mass abductions — have targeted schools across the country, such as the Chibok girls abduction, and the abduction of several other schoolchildren, including those in Niger State who were abducted in Feb. 2021.

Even though research has not directly linked illiteracy to the unbated security crisis grappling Nigeria, including growth of terrorism, research has found that “social institutions, like schools and universities, have not been sufficiently supported to effectively foster resilience in students to resist the pull of extremist ideology and narratives.”

The same research shows that more and more young people are being radicalised through narratives and propaganda.

Thus, a high number of school dropouts in terrorism-ravaged regions such as the Northeast and North-central are potentially harmful, as children who dropout from primary school levels become more vulnerable to indoctrination into these groups, making them radicalized towards formal education, and in turn, join groups that legitimize or strengthen those notions, even if unintentionally.

Many Nigerians, especially from the north of the country, but also as far west as Lagos, have shared stories of attempts by extremists to radicalise them against formal education while they were in primary school, through sermons at ‘Islamic’ schools.

“I was in Primary five then,” Hafsah* tells HumAngle. She and her friends had tried to explain their late-coming at the Islamic school to their tutor, saying that they were often late because they finished late from school.

The tutor then dedicated an hour to delivering a sermon to the entire class, to encourage them to ditch lessons at school. “He said that if only we knew how Islamiya was our only path to redemption, we would leave our lessons and come to Islamiya. He told us that if anyone tried to stop us, we need only tell them that they can never understand, because we were believers and they were not,” she recalls. The man was later dismissed because of his many other problematic views.

The sermon isn’t so different from the sort often delivered by Mohammed Yusuf himself in Borno State, while trying to radicalise young men into abandoning school and joining Boko Haram which he had just founded (or scrapped off other similar groups) in the early 2000s. He has been heard to spin theories to students on how schools existed primarily to pull them away from their religion. At the stage of these radicalisation exercises between 2002 and 2006, the group was not visibly violent. However, around 2007, after it had gained a large following from these sermons and other ways, it started to launch its attacks. In 2009, after skirmishes with security forces under the banner of Operation Flush, the group launched an uprising.

While Boko Haram has a deep and wide membership that consists of both school dropouts and fully educated people, both Mohammed Yusuf and Abubakar Shekau who are considered its founders, had no solid conventional education.

It may be easier to convince school dropouts with these theories. Hafsat, who was not a dropout, and who took everything her tutor said to heart, started to walk out of classes mid-lessons, and declare to her teacher when queried, that she would not understand, as she was an unbeliever.

This suggests that indoctrinating children who are already dropouts might be easier. Thus, inadequate educational systems have the potential to heighten and feed radical, anti-school ideologies among children.

Way forward

For Malam Idris, a total overhaul of the primary school system in Niger State is what is needed. “First and foremost, Niger State must do away with the Alfurma system when employing teachers,” he says. By the Alfurma system, he means Political patronage, Alfurma being the Hausa word for favour.

“Strict priority should be given to the TRCN condition. No teacher should be employed if they are not certified as professional teachers … Education is a right, and the children are innocent. They deserve quality education.”

Primary school education plays a crucial role in honing problem solving skills, and emotional and intelligence skills, according to the national curriculum. Primary schools are important for national development and achieving sustainable peace. As such, it is imperative for the government to prioritise it and generally incentivise education especially in low income communities.

Names in asterisk have been changed to protect the identity of the respondents.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter