Animals: Voiceless Victims Of Armed Violence In Northwest Nigeria

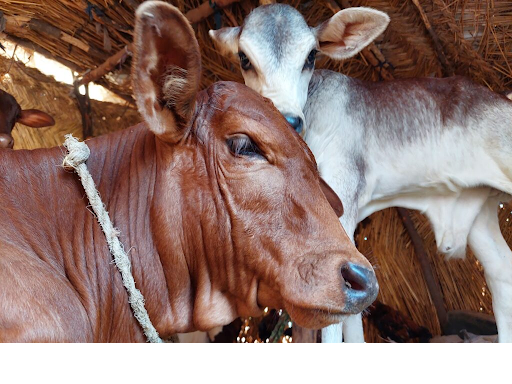

Humans occupy the central focus of media reports as victims of armed violence. But livestock like sheep and cattle, central to the lives of so many people in northern Nigeria, also suffer brutality and purposeful cruelty at the hands of terrorists.

A terrorist group recently stormed the Kurya-Madaro community of Zamfara, where they took away herds of cattle and sheep.

But one animal they did not take with them was a large, healthy, valuable bull.

“A bull, too big to move fast, was gunned down by some sadists among members of the group, while they carted the rest of the animals away,” narrates Bello Ibrahim, 35, a resident of the neighbouring Kasuwar-Daji community.

This was only one of the countless unreported incidents where rustlers were cruel to animals against the backdrop of lingering insecurity in Northwest Nigeria. The rustling of animals, where no human has been injured, may not appear in the media.

But the cruelty to animals was not arbitrary or senseless. It had a grim purpose.

When rustling livestock, terrorists often shoot down any animal that becomes difficult for them to move, preventing the rightful owner from recovering it. Also, by removing a stubborn animal from the herd, it increases the likelihood the rest will not follow its example.

As well as being ruthlessly pragmatic, the shooting of a valued bull sends a message: the terrorists are cruel people who will destroy the things you value.

While Nigeria does not have a stand-alone law to protect the rights of animals, its Criminal Code outlaws animal cruelty. This includes killing an animal in the process of stealing, injuring animals, or doing anything that may cause suffering to them. Last year, the federal government also established the National Council on Animal Welfare to ensure “that animals are treated humanely, responsibly and devoid of stress, hunger, anxiety and pain”.

Cruelty to animals, Saheed Aderinto writes in his book Animality and Colonial Subjecthood in Africa, has been illegal in Nigeria since the 1940s when the first laws enabling the prosecution of people who inflicted brutality against animals were introduced.

Despite increased knowledge of animal rights, rising insecurity has made the unjustifiable killing of animals rampant in the last decade. Thousands have been mercilessly macheted or killed in the melee between farmers and herders across the country or caught in the web of banditry.

But in a situation where the terrorists are murdering people, kidnapping women and chasing people from their villages without effective censure from the law, cruelty to animals has a tendency to slip down the list of importance.

The rustling of domestic animals, a central aspect of the ongoing armed violence in the Northwest, has led to unprecedented animal brutality. It has also led to changes in how people interact with domestic animals in rural areas. Herds have disappeared from insecure areas across the Northwest.

Animal brutality

Herd animals have more than a cash value in Nigeria. They are stores of wealth and status symbols.

As assets that are easily convertible -and mobile, to a degree- herd animals are exceedingly desirable and are much stolen. For armed groups engaged in banditry, animals are more desirable, in many situations, than cash.

Although no category of domestic animals is exempted from terrorist violence, cattle and sheep – the most rustled animals – are more likely to be affected.

“Only a stupid ‘bandit’ rustles goats,” says security expert Dr Murtala Ahmed Rufa’i. “Cattle and sheep are enduring and they move faster and cover a long distance within a very short period of time without any problem. But goats make a lot of noise and even the market value of goats is nothing to write home about.”

Rustlers prefer cattle to sheep, and target them more.

Ashiru Sani, a 30-year-old refugee in the Sokoto metropolis who is displaced by the ongoing carnage in Sabon Birni Local Government Area (LGA), shares an incident that happened in Garin Tunkiya, about 3 kilometres away from his hometown of Gatawa.

“When the terrorists came, they gathered cattle from different households with the intention of chasing them away. However, a very strong bull, belonging to my father’s younger sister, proved stubborn to them. Whenever they chased it out of the compound, it forced itself back. The bull defied all the terrorists’ efforts to chase it with them. They suddenly used their gun and shot it down.”

The owners rushed to slaughter it, but the terrorists stood there, vowing to gun down whoever moved close.

In many societies, it is considered a ‘merciful act’ to sever the throat of a suffering animal that can’t be treated. And according to the rules of Islam, which is practised by most people in the Northwest, slaughtering the bull would legalise its meat for human consumption. By preventing anyone from cutting the beast’s throat, the terrorists were demonstrating the lengths they would go to harm. If they could not get their way, no one would, not even as salvaged meat.

Dr Rufai explains that what happened in Garin Tunkiya is common in communities terrorised by criminal groups all over the Northwest.

“I have seen a lot of cases like this in Tsafe, Birnin Magaji, and Moriki in Zamfara. I have also seen similar cases in Bargaja, Kamarawa, Bafarawa, Gwandi, and Mageriya in Isa Local Government Area, Sokoto. I have also received reports on similar cases in Kaura Namoda. In fact, it is commonly seen in pastoral communities,” he says.

The security expert explains that terrorists’ brutality against cattle stems from the rustlers’ understanding of animal husbandry.

“Many of the bandits were herders before they joined criminal gangs. They, therefore, have enormous local and village intelligence of the ties and bonds between the cattle and their owners. Normally, cattle owners call each cow by its name; and the cattle can identify their owner by body scent.

“The owners usually pick one or two cattle in a herd and train them to lead the herd at the front. They call it the Jagaba. It must lead before others follow.”

Whenever a herd of cattle is rustled, Dr Rufa’i explains, the rustlers pay attention to identify the Jagaba. If it does not mobilise the rest of the herd where they want, they shoot it down.

They generally believe that any cattle that prove stubborn to them will likely be traced by the owner after they are sold or stolen.

The danger of owning domestic animals

Although domestic animals have been part and parcel of rural life in Northwest Nigeria, the ongoing armed violence in the region has made having them a huge risk.

“In Sabon Birni, once you have cattle, you will never have peace of mind. You are sure that cattle rustlers can storm your house at any time. But some diehards still keep cows,” explains Ashiru.

He estimates that cattle in his community, Gatawa, have shrunk from about 5,000 two years ago to only 20. Most of the cattle, he says, were stolen by the terrorists; but a few were sold by the owners out of the fear that they could be rustled.

In Garin Idi, located a few kilometres away from Gatawa, virtually all the cattle were taken.

The town, Ashiru explains, has a rich marshy land on which the people feed their cattle. As a result, it acquired regional fame in the eastern Sokoto region for rearing the biggest and healthiest cattle. But there is no single herd of cattle in the community today.

Dr Rufa’i says this is a growing trend. “Go to Kukiya in Birnin Magaji or Gidan Kaso, for instance, you will find virtually not a single herd of cattle. In many communities where you find a few cattle, you will find that the cattle belong to people who are related to the ‘bandits’.”

“Some communities with a substantial number of cattle establish peace pacts with the terrorists so that their cattle will not be rustled. This is especially common in places in Isa, Shinkafi and Kaura Namoda in Sokoto and Zamfara states.”

The situation is more severe in the eastern part of Sabon Birni where, according to locals, more than a hundred communities close to the Nigerien border are under the terrorists’ control. These include Burkusuma, Gudun Banga, Kwarin Dabi, Na Gamawa, Magira, Tulurudo and Gangara, among many others.

According to a traditional title holder in Gatawa who asked not to be identified, there is presently no single domestic animal in any of those communities.

“The terrorists have already exhausted all their victims in those communities. You cannot find a single animal, not even ordinary goats. In fact, even hens and guinea fowls that are reared by women are not spared. They catch the birds and eat them up. It is pathetic that in these villages where they used to rustle cattle and sheep, you cannot find even a hen today.”

Today, in many rural communities across the Northwest, terrorism has forcefully separated domestic animals from rural life.

Marwanu Muhammad, 31, a displaced person from Gatawa stresses how widespread the problem is.

“If your wife gives birth, you cannot buy and keep an animal before the naming ceremony. You can only buy the animal on the day of the ceremony, and even then you have to hide it for it to be safely transported into the town. Even after you successfully take it home and slaughter it, if the terrorists heard the information, they would storm your house and seize the meat.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter