Abortion Amongst Displaced Women Reflects Deeper Societal Problems

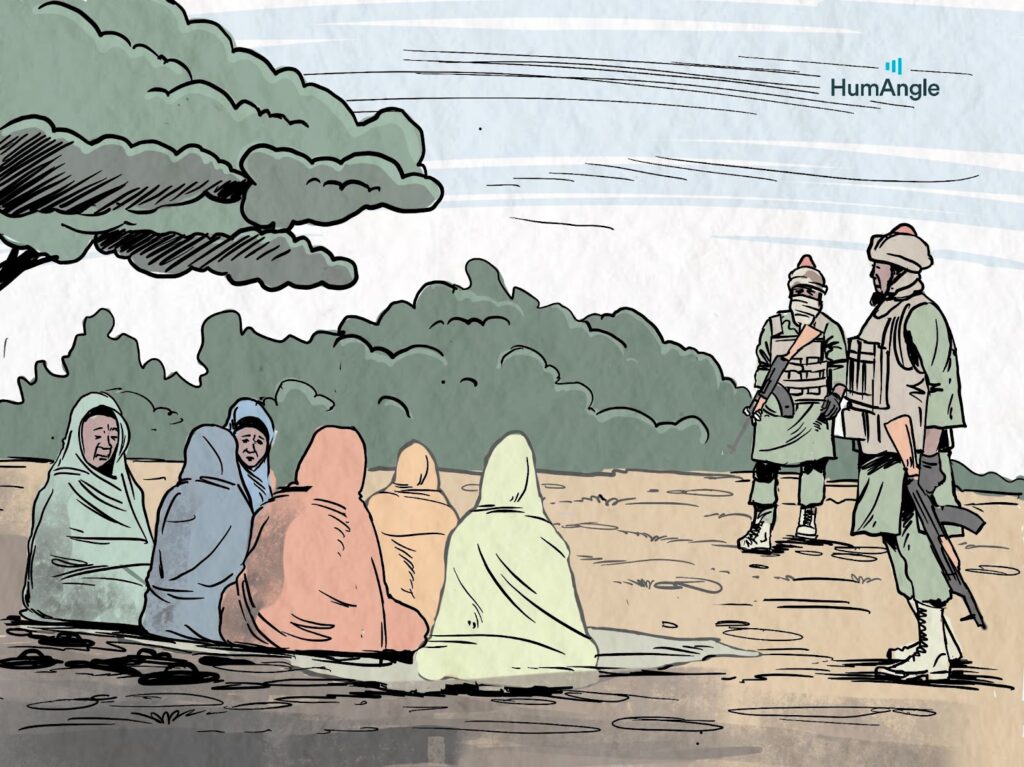

Displaced women and even women in captivity in Northeast Nigeria attempt abortions despite laws insisting otherwise, but at what cost?

One day at around 3 a.m., a camp for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Maiduguri, Northeast Nigeria, was roused awake by cries from a woman in pain. Some of the women leaders were stirred from sleep. One of them was Aisha Kumshe*.

By the time Aisha got to the wailing woman’s tent, she says, she was in great pain and bleeding so much that her screams “seemed to be coming from deep inside her bones.”

It was not the first time her attention would be drawn to an emergency at odd times, because of her status in the camp. She has even once been called to help cage in a woman who had run out of her tent, naked, having developed a mental illness.

Still, this was something utterly unprecedented.

“We did not immediately know what was going on,” Aisha tells HumAngle. They also did not know before that she was pregnant because her husband had not been around in years. “So nobody thought along the lines of an abortion.”

Her husband had been part of the thousands of mostly displaced persons in Borno who had been detained by the Nigerian army on allegations of being Boko Haram members in 2014/2015. They had both been displaced from their town by the insurgency. He has been in detention for seven years now and she hasn’t seen him in all those years. She also had not remarried. Marriage is a prerequisite for pregnancy in many Nigerian cultures and so her pregnancy in the absence of a husband was deeply puzzling.

Aisha tells HumAngle that she learned while trying to help her that she had made a paste of powdered pepper and detergent, and drank it in an effort to abort the pregnancy.

It is not impossible that she might have been trying to kill herself.

When the foetus finally got expelled from her body that night, some of its body parts had already formed, suggesting that it was a pregnancy that was already far gone. As she lay bleeding and in pain, her first son knelt beside her, alarmed and unsure what to do, weeping.

“We buried the foetus the following morning and the elders in the camp sat her down and warned her never to try it again,” Aisha recalls.

Women in IDP camps are often forced into sex for food, or sometimes sex work, to get food for themselves and their children. Sometimes it results in pregnancy. But there is no way to tell if this was the case for the woman.

Perhaps it was the shame, or the trauma of having gone through something like that, or maybe she feared that with so many people now aware of what she had done, she might no longer be safe, but the day after, the woman packed her things and snuck away with her son.

“We haven’t seen her since, but we are told by her new neighbours in the current IDP camp she’s staying at that she’s doing fine. We speak over the phone too from time to time.”

She is in a different town now. When HumAngle tried to reach out to her multiple times, she evaded each meeting. Sometimes she agreed to meet but would eventually not show up. Other times she simply did not respond — her reluctance understandable given the circumstances.

Her social and economic class highly influenced her choice of abortion method. But if she had opted for a safe medical procedure despite her highly limited means, she still may not have gotten it because, according to Nigerian laws, abortion is illegal. Nigeria operates with two broad sets of law: the Criminal Code in the south and the Penal Code, which governs the northern states. Both laws criminalise abortion completely, except where it is necessary to save the mother’s life. This prohibition has done little to curb abortion rates in Nigeria. It has only served to exclude poor women — such as displaced women and those forcefully married to insurgents — from any version of the procedure that might be safe.

In fact, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research and policy NGO that aims to improve sexual and reproductive health and rights worldwide, an estimated 610,000 unsafe abortions are done in Nigeria every year. Some researchers have argued that the only way to truly minimise it is to legalise it.

Estimates about abortion rates are likely very conservative because the research methodologies often involve sampling cases in urban areas through health facilities. For the statistic from the Guttmacher Institute, for example, physicians conducted interviews “at a nationally representative sample of 672 health facilities in Nigeria that were considered potential providers of abortions or of treatment for abortion complications.”

But abortions are so rife that they are not done only by women in urban areas, who have access to healthcare facilities, or displaced women, they are also done even within women who are in Boko Haram captivity.

Abortion while in captivity

One day during a sermon from members of the Boko Haram terror group to their women captives in the settlement where they lived, the Imam spoke about the sinfulness of existing in a place like Nigeria.

Fatima Mohammed* sat there with her full-length hijab, listening, like all the other women. He talked about how dying on Nigerian soil could earn them a place in hell. He also talked about how running away from the settlement and to Nigeria with children they had born for the insurgents through forced marriages was a grave, unforgivable sin.

“They say Nigeria is an infidel country,” Fatima says.

“That even the constitution is wrong. They say that the system of government that they practise in the forests is the right one, and if we die there, we will go to paradise. But if we die practising what Nigeria is doing, we will go to hell… They always say if we take their children to Nigeria, they will never forgive us. They will find us, wherever we are.”

The sermons were always along these lines.

Sometimes, they also warned them against abortion. These sermons were scarce, however. It was hardly because there weren’t cases of abortions but because they were usually discreet and well-hidden. This part of the sermon was what turned Fatima’s stomach with fear. She had tried to do all the other things they had been warned against — attempting to run away — and she had been punished first with a hundred lashes of cane and then by being locked up in prison for two weeks. But she did not know what the punishment for abortion could be. Perhaps death. Perhaps prison.

Still, when she realised one day that she had missed her period, she knew there was only one option for her.

It was not an easy decision to make, as no medical supplies were reaching them in the settlement. Even childbirthing conditions were so bad that one woman reported having to use a stick to cut the umbilical cord after giving birth. She told HumAngle that there was a high maternal mortality rate.

There was also no menstrual hygiene support of any sort. A woman told this reporter that she not only had to use rags for her periods while in captivity, but she also had to cut rags into ropes, to stand in as underwear capable of holding the makeshift pads in place during her period. Because she had no panties.

With conditions like these, safe abortion procedures, no matter how important, were a stretch.

Still, whether safe or not, it was certainly possible, and Fatima was going to do it.

“My friend had done it before and it worked. She vowed that she would never bear a child for a Boko Haram member, so when she found out that she was pregnant, she told me that she was going to abort it.”

So her friend got roots and seeds from a tree she called Kangar, the Kanuri term for the Acacia tree. It is known in Hausa as gabaruwa. Based on the descriptions she gave, some botanists HumAngle consulted say that it is the species known as acacia nilotica (Gum Arabic tree).

After using it, she bled so profusely that the blood had major clots in it, Fatima says. She nearly passed out. But she successfully got rid of the pregnancy.

Fatima decided she would do the same, especially as she was merely two months gone. The acacia tree dominates the Sahelian parts of Borno and the insurgents are known to make camps underneath due to the nature of the branches and the concealment it provides. They spread into a neat, nearly impenetrable umbrella that makes it difficult for people under them to be spotted from above.

“The trees were everywhere,” Fatima says. “It’s there like water. We used it for many things. It is the only thing we had in abundance.”

She found the seeds and roots and made a consumable mix out of them. Then, she drank it.

She did not feel anything abnormal immediately, she says. But later she started bleeding, and she saw there were clots in it as well. Her period returned to normal the following month.

The Acacia tree and its seeds have been known to have abortifacient elements.

Literature shows that it is possible to cause abortion when the pods are consumed in large amounts. Research also shows that Afghan and Egyptian women use it for the same purpose. “Body heat ferments the acacia, breaking the gum Arabic down into lactic [acid], which is used today in spermicides.”

Rukayat Omowunmi Muhammed, a botanist and online fertility coach, also explained its use as a spermicide.

“The acacia plant has abortifacient uses which consist of the gum, roots and even the leaves … The leaf can be ground to a powder and mixed with honey used by men as a spermicide,” she said.

Still, Oluwatobi Oso, a PhD student at Yale University studying plant anatomy and evolution, advises caution on making blanket statements on the use of the tree as a successful abortion alternative.

“There isn’t enough information in literature to take such claims hook, line, and sinker, and so I would be careful with making a blanket statement,” he says. “In research, even if locals make certain claims about certain plants that may be true to the people locally, scientists (ethnobotanists and others) don’t take it hook, line, and sinker unless there is research to prove it, over and over again.”

The tree seemed the go-to for women captives of the terror group for contraception and birth control, despite its illegality.

Even though the illegality of abortions in Boko Haram-governed territories is premised on religious principles, Islamic scholars and academics seem to largely agree that it is permissible in the first four months of pregnancy under certain circumstances: such as to protect the woman’s emotional or physical health (in this case, it is permissible at any stage), or where the pregnancy was a result of rape or any other circumstance that was beyond the woman’s control, or where medical experts say that the foetus will be born irrevocably deformed and the mother feels she will be put under unbearable strain to care for it.

“The one prevailing commonality among these and diverging Islamic views on abortion is the Islamic concept of God’s mercy and compassion,” Zahra Ayubi, Associate Professor of Religion at Dartmouth College wrote.

*All names have been changed to protect the identities of persons interviewed due to the sensitivity of the topic.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter