Abandoned Public Hospitals Pushing Nigerian Villages Into Deadly Health Crisis

In Malamari and Waddiya communities of Borno State, authorities leave public healthcare centres unused or repurposed, plunging disadvantaged residents into deadly health crises.

On the outskirts of Borno, North East Nigeria, Malamari village grapples with a dreadful healthcare system, causing distress for about 5,000 residents. Three years ago, authorities completed a primary healthcare centre in the community, but the building remains locked, plunging the community into a looming health crisis.

The village head, Bulama Abba, says the escalating demand for reliable healthcare is affecting women and children. Ailing pregnant women and children are conditioned to travel to a distant Borno State Specialist Hospital. The long distance, Abba notes, has resulted in tragic outcomes due to transportation and financial hurdles.

The hospital is about 10 kilometres away from Malamari. Residents depend on the tricycle transport system, which is often problematic in the area. The three-legged vehicles are usually scarce at night.

Fati Sani, a resident living adjacent to the dormant government hospital, says her experience during recent childbirth was hellish, stressing that several women in the community lost their lives over a lack of reliable healthcare service.

“I had no antenatal care because of so many challenges like the long distance and lack of money to visit town for such maternal services. My husband is doing menial jobs in the town, and most of the time, he could not afford the food for us to eat in the house,” Fati tells HumAngle.

When it was time to deliver the baby one afternoon, Fati’s husband insisted they go to the hospital in town. She remembers trekking a long distance to the main road with her husband by her side before boarding a tricycle.

Fati says living beside a newly built government hospital under lock is disturbing, especially when she recalls the hardship she faced during and after childbirth. Her family, consisting of her husband and three children, depends on drug vendors hawking in and around their village.

“When my children fall sick, especially when they have malaria or a cough, I just wait for drug vendors to come. Most of the time, we wait, but the vendors will not show up, and that is how the children will heal naturally without any medical care,” she adds. “Although we are mostly lucky we get better by whatever they give us, we are still not satisfied with the whole idea of not getting drug prescriptions from the hospital.”

Meanwhile, Zainab Musa, 64, mourns the loss of her grandchild to severe malaria, a death she believes could have been averted if the local hospitals were functional. She urged the government to open and equip the new health facility in Malamari.

Awana, Zainab’s grandchild, fell severely ill one night and getting transportation to the hospital in town was difficult. The boy died as the day broke before they could reach the Borno State Specialist Hospital.

She had adopted her only grandchild from his parents to reduce the burden of finances on them. Zainab says Awana’s parents have financial challenges, and she would not like her grandchild to be raised in such poor living conditions.

“I love him, but what else could I do to save him? We just stare at the completed healthcare facility built by the government,” she groans.

Babagana Goni, another resident in Malamari who has 15 children, laments instances of preventable child deaths over the absence of local healthcare. Babagana lives with his three wives, but a lack of accessible healthcare services makes life difficult for him and the family.

“Our community doesn’t have a functional health facility that will cater for our health issues. We are predominantly farmers doing small-scale farming, we are a poor community that needs help,” Goni says. “This is sad because we will be mourning the death of an innocent child who could have been saved if we had a clinic in our community.”

When they run into health emergencies at night, villagers say they are helpless. In some cases, they add, one Bukar Tela, the chairman of the Civilian Joint Task Force group in the area, had rescued several people in dire need of transportation to the hospital in town.

The burden on Bukar is heavy. Sometimes, he is called up even during curfew hours in the metropolis by families of ailing residents seeking his help. “I don’t have a choice. In the middle of the night, when I am resting with my family, I hear a knock on the door. My wife has grown accustomed to it because of the frequency of people seeking my assistance,” he says, noting that he has now exhausted his resources in helping people in need of medical attention.

“I use my patrol motorbike and buy fuel with my money to convey people to the distant hospital in town. I have a family, my salary has never been enough and coupled with this demand, I am rendered poor and helpless.”

In Waddiya, another remote community in the Jere area of Borno, a hospital stands empty, devoid of staff and equipment. Now, the building has been repurposed for distributing therapeutic food by non-governmental organisations, leaving the community in desperate need of basic healthcare.

The lack of healthcare facilities in Malamari and Waddiya is affecting over 5,000 residents in each community, according to community chiefs and village heads. HumAngle has reached out to the State Primary Healthcare Development Board in Borno for comment, but we have received no response yet as of the time of publication.

Residents of Waddiya, like Abba Umaru and Falmata Umar, recounted their harrowing experiences of giving birth at home over a lack of quality healthcare.

“My wife started labour in the night, and we don’t have a hospital in our community. She had to give birth in the room. I supported her to deliver the child with the little resources we had in the house,” Umaru recalls.

Umaru says it was the first time his wife would give birth at home. She had slipped into labour at night; help didn’t come until she delivered her baby. “I was scared because I never encountered such an experience and I was afraid because I thought the child would die,” he says.

Umaru, 34, now lives with his eight children and the newborn. The poor healthcare system has cost them a lot and drained them financially. For his wife, Falmata Umar, remembering the experience of giving birth at home moves her to tears.

“I delivered the baby alone and did everything that was required. We have a hospital, but it is not working. I suffered a lot because it was risky for me to give birth at home without any professional assistance,” she tells HumAngle.

Waddiya, a community mostly occupied by farmers and fishermen, lacks basic healthcare. The community residents fear looming health crises; they are already overwhelmed by widespread malaria, while expectant women are left with no medical care.

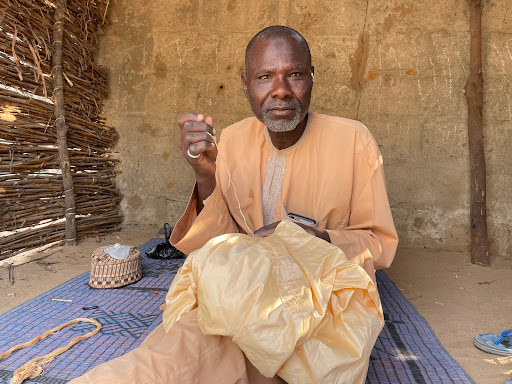

As the only community hospital remains dormant, villagers like Abbakar Ali, a 53-year-old cap vendor, say they spend a lot from the little they earn on drugs.

“The little I get from this trade, I spend it on drugs and some medical expenses of my children when they are sick,” Abbakar says. “We are not happy that the government built a non-functional hospital for our community. We need healthcare in Waddiya.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter