A Military Officer Locked Up Her Husband, Then Proposed To Marry Her

Between 2014 and 2015 when the Bama Hospital Camp was set up in Borno for people displaced by the insurgency, serious human rights violations, especially sexual abuse, were recorded. Falmata Abubakar is one woman who was continuously victimised by the man who detained her husband.

He usually didn’t come with a convoy. That day, he did.

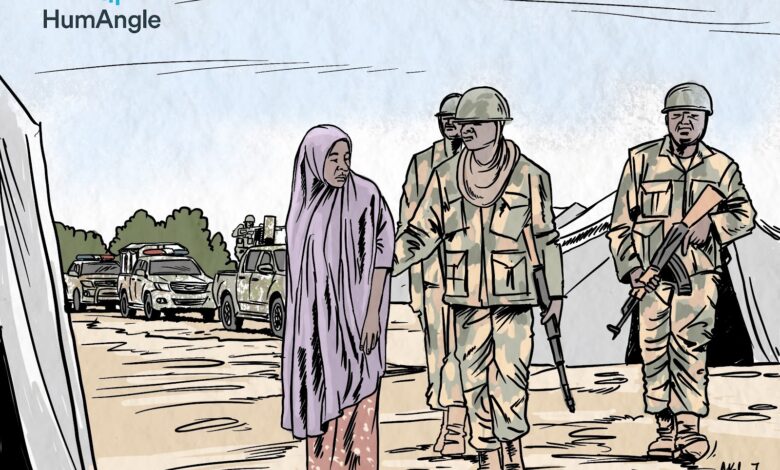

He arrived in his car blaring the siren, several other cars behind him. Some of his men came down from the cars that trailed him, after parking inside the Bama Hospital Camp in Borno, northeastern Nigeria, where Falmata Abubakar* lived at the time. It used to be a hospital, then it was burned down by the Boko Haram terror group. It became an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp.

The men went into her tent and grabbed her, then pulled her out.

She had never felt that much fear, confusion, and dread in her life. Still, she knew what was about to happen.

She was thrown into one of the cars and pinned down as they drove to a destination she had no way of knowing.

When they arrived, the military officer, heavily built and slightly light-skinned, with a tribal mark slanted horizontally across one cheek, took her into a deserted building. There, he raped her.

“There were so many deserted buildings in Bama in those days,” she remembers.

Afterwards, he asked his men to drive her back to the IDP camp.

“When he finished doing what he wanted to me, he asked his men to return me.” There is a resigned and detached tone to her voice.

There were many more ‘deserted building’ episodes after that day. With time, the violation began to happen in her tent at the IDP camp. He would arrive with his convoy, blaring sirens, his car full of relief materials for the displaced people. As people scampered to offload the materials and share it among themselves, he was usually in the tent raping her. There were times his men had to hold her down.

Seven years later, the sound of sirens still troubles her. She also panics whenever she sees a man walk briskly out of a room. He used to walk briskly out of her tent each time he raped her. She spends long hours lost in thoughts.

“I recently misplaced my phone. It was not stolen. I was just lost in thoughts and no longer remembered where I had put the phone.” She has bouts of deep thinking that disrupt her consciousness and sense of time like that.

Even now, her voice is low, and her eyes glued to the ground, as though if she raises her head she would find him standing in front of her. Her nose ring, oblivious of the anxiety rocking her body, glistens brilliantly against the scorch of the sun.

People knew. They heard her struggle, sometimes they even saw it happen. There were also times she successfully ran away and sought refuge in other people’s tents. But they could not help her for long. The most they could do was advise her.

“They told me to just accept and marry him. So that all the suffering would stop, and so that I could also have unlimited access to food […] He was also a high-ranking military officer, so nobody could stop him.”

She could not agree to his marriage proposal because she was already married.

Where was Falmata’s husband?

In 2015 when Boko Haram took her village, Nguro Soye, Falmata Abubakar and her husband fled like everyone else. They arrived at a nearby village and stayed for some time. It was a restless stay as they soon realised that the village was under Boko Haram control too.

“We had left our village in search of safety but even that place was not safe. We were stuck.”

And then one day she and her husband heard on the radio that the government had pledged to accept and accommodate all the displaced people who were brave enough to make it out of the villages that had fallen to Boko Haram. Most of the villages were at the fringes of Bama Local Government Area (LGA).

“The government was calling on us, assuring us that there was space for us in Maiduguri [the state capital], that if we made it there, we would be accepted with both hands. So my husband told me that it was better for us to leave, because there was nothing for us there in the village. ‘The village cannot hold us.’”

So they packed their things and left in the middle of the night to avoid running into the insurgents. There were people who did run into them and were shot at. But she and her husband made it to Bama by morning. When they arrived, they were accosted by soldiers who stopped them and interrogated them.

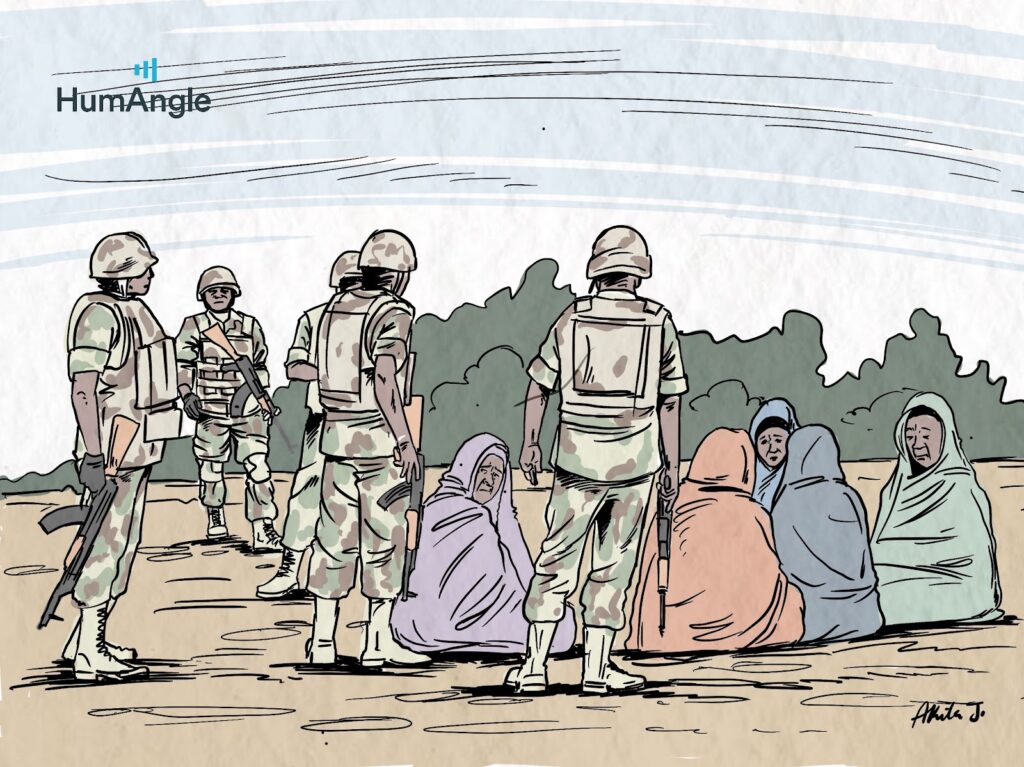

“They asked us to bring down our luggage from our heads and we did. Then they asked us to raise our hands and we did. And then they asked us to sit on the floor,” Falmata tells HumAngle.

Then, they were transported to another place in Bama where they were again questioned about their identities and previous location. There were about seven Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) members and about three military officers at that checkpoint, Falmata says. One of the soldiers was heavily built and had a tribal mark slanted across one cheek. Suddenly, he grabbed her husband, began to bind his hands together and then tied them behind him. They began to beat him up.

“When they tied him up and started beating him up, I started crying. And they warned me to stop crying. They said if I thought they were being cruel to my husband, they hadn’t even started yet. And then they took me away.”

The same thing was done to a number of other men. They would later realise they were being detained on suspicions of being part of Boko Haram.

After, she and all the other women were taken to the Bama Hospital Camp where they would proceed to witness and experience severe starvation, she said. The starvation in the camp around this time has been reported to have been so severe that as many as 20 people died on some days.

“People were either falling ill or dying. Daily. There were days 20 to 30 people died. Those that were sick, whenever they made it to the hospital, the doctors would say after examining them that they were not sick, they were only starving.”

Slowly, she says, when medical help started to come from organisations like the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), especially for their children, they settled into life at the Bama Hospital Camp.

The military officer

One day, as she stood in line waiting for her turn to grind grains for pap at the commercial grinding machine inside the camp, she caught a glimpse of the military officer who first struck her husband that day. His eyes met hers too. He attempted to talk to her.

“He said, ‘Oh, hajiya, you are here? I didn’t know.’ But I refused to answer him. I just ground my grains and went back to my tent.”

She would later learn that the officer had asked a boy to follow her and find out where exactly she lived. The day after, the man came looking for her, holding a flask of food.

“I was furious. It was him who detained my husband and had him taken to Maiduguri, how could he now come with food for me? When he knew I was a married woman? I told him not to ever come back again.”

She did not know at the time that he was high-ranking.

He assured her that her hopes of her husband ever returning were misplaced.

“He told me to forget about my husband because he was never coming back and so I should marry him instead. I refused to marry him.”

The man came back every day with a flask of food, asking her to marry him. Despite the severe hunger in the camp, it was not strong enough to conquer her fury and make her accept the food nor his proposal, she says.

A curious situation was also going on in the camp where soldiers and members of the Civilian JTF gave food to women and demanded sex from them after, and in some cases outrightly raping them, she says.

It was a widespread problem at the time, so widespread that, in 2018, Amnesty International found in an investigation that thousands of women and girls displaced by the insurgency in the Northeast around 2014 and 2015 had been abused by Nigerian security forces in satellite camps such as the Bama Hospital Camp. The report found that women who had been separated from their husbands and confined in camps like that by the Nigerian Army were raped, sometimes in exchange for food.

In 2016, three army personnel were arrested for raping displaced women, following a report by Human Rights Watch which documented cases of 47 women and girls being raped across six IDP camps in Borno.

HumAngle found the same situation in a report in 2020.

Falmata was aware of all these and determined not to let it happen to her. And so she never took his food. She believed that would be enough.

“There was a day that a soldier who had been bringing food for a woman tried to rape her,” she says. People around there heard the commotion and had to intervene to stop the man from having his way. “We had to run into the tent to save her from it.”

Despite her refusal to accept his marriage proposal and food, he grew so persistent with his visits that she would run into hiding whenever she saw him.

“He always told me that, despite my running, sooner or later he would ‘catch’ me.”

One day, she was sick and bedridden. When he came in, he asked what was wrong and saw that she was sick. Seeing her frailty, he started trying to forcefully undress her, she tells HumAngle.

It was the first time he attempted to rape her. Stunned by his brazenness, she screamed and dashed out of the tent, calling on people to come help her. He disappeared.

The next time he came, it was with the convoy.

Escaping…

When the sexual abuse got unbearable, she went to a trader she was familiar with, who lived within the neighbourhood. She told him of her troubles. She needed to leave that environment and needed his help.

“That soldier is the reason I left that camp. If I didn’t leave, he would not have let me be. I told the trader that I had some caps that I had knitted myself and was ready to sell to get money that could transport me out of that village.

The trader was compassionate. She sold the caps and earned ₦5,000. When a truck came into the village to drop off food supplies and building materials, he smuggled her in to go back with the truck.

Years later in her new location, she would hear from her former neighbours that the military officer often came looking for her, asking where she now lived, attempting to trace her.

For years she heard no word of her husband. And she started to believe that perhaps the officer was right that she would never see him again. But he turned out to be wrong.

Because six years later, her husband was released.

This report is a partnership between the African Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) and HumAngle Media under the ‘Mediating Transitional Justice Efforts in North-East’ project.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter