A Lone Walk To Justice

An aged mother whose son was “wrongly” picked and detained by the military as Boko Haram suspect embarked on a lone mission to secure his freedom. But her effort continued to hit the rocks as she was ripped off several times by officials. Ten years later, her grandson, who was born three months after her son was taken, has now joined her in the fight for justice.

Once upon a time, 11 years ago, during the early years of Boko Haram, a young man in Maiduguri, Northeast Nigeria, set out to join the early morning congregational prayer at a mosque not far from his home in Bulabulingaranam.

Buluabulingaranam used to be the den of Boko Haram terrorists when the terrorists reigned supreme in the township of Maiduguri, the Borno state capital. The suburb was once a no-go area to the military.

It usually takes about 20 minutes to conclude the prayers, and everyone returns home to prepare for the day’s task. But that was not the case for Mustapha. It has been over a decade since he left home on that fateful morning.

When the Imam announced the salutation to end the prayer, little did the congregants know that a deployment of military troops had surrounded the mosque.

Every worshiper that stepped out of the mosque was rounded up and asked to sit on the dusty floor outside. Later, other male neighbourhood residents were equally fished out by soldiers who were moving from house to house and made to join the gathering of the apprehended.

Anyone who dared to challenge the soldiers’ actions got the butt of the AK-47 crashing down on his head or shoulder. So, they allowed wisdom to prevail by quietly waiting to see what the soldiers wanted from them again.

Later, the soldiers sorted out the elderly males and asked them to go home. In contrast, some of the young were labelled Boko Haram accomplices responsible for a recent attack on a nearby military post.

It was Mustapha’s turn to be interrogated. The soldiers marched him, at gunpoint, to his house, where he lived with his then-newlywed wife, Nafisat.

Mustapha was made to open the gate to his two-bedroom bungalow, and the soldiers ransacked his house, searching for hidden weapons or anything that may link him with ongoing violence in the city.

“They found nothing, and then one of the commanders told the soldiers to take him away, while my husband kept begging them to free him because he is not a member of Boko Haram,” Nafisat recalled.

The soldier dragged Mustapha out of the house even as his wife held onto him and begged them to free her husband. She had to let him go after one of the soldiers smacked her.

That was the last time his wife, six months into a pregnancy that would later produce her only child, would ever see him again.

Searching for Mustapha

Hajja Gana, Mustapha’s mother, would later be informed about the arrest of her first son.

Known as an activist and labour unionist during her days in the civil service, Comrade Hajja Gana began the fight to free her first son, whom she swore was never a member of Boko Haram. She did not anticipate that her quest to free her son would last for ten years.

Like many other suspects of Boko Haram terrorism, the soldiers took Mustapha and others to the Giwa Barracks military detention facility in Maiduguri.

His mother would later trace him there, where she practically paid her way through some crooked soldiers to see her son.

“About three weeks after his arrest, I saw my son at the Giwa Barracks,” she said. “A senior military officer, a Colonel, asked that he be brought out of the cell.”

“My son begged me to do everything I could to ensure his release from the detention facility. He said, Mama, help me get out of here because this place is not a good place. The soldiers told us it would require a lot of money.”

Mustapha, who used to trade wholesale goods that he usually bought from Kano and sold to retail shops in Maiduguri, gave his mother a list of his business partners whom he said owed him money. He wanted her to get that money and use part of it to secure his release.

Extortion

Hajja Gana said she managed to retrieve her son’s money from his business partners and used it to get a lawyer and also pay some of the soldiers who claimed they could help her secure his release.

“I got all the money, but it was not enough. I had to sell my personal effects, my gold jewellery pieces, my savings, my landed property, and anything valuable to raise money.

“The soldiers kept asking me for money with the promise to help me bring him out. They told me my son would never be freed alive unless they sneaked him out. That people die every day in the cell, and they would include my son among the corpses to be evacuated to the mortuary so that I could go there and take him home.

The poor woman estimates that up to N2 million ($4,800) had been extorted from her so far.

“There was a time they asked me to provide N25,000 ($50) for them to service and fill up the tank of one of their vans so that they could sneak him out of Maiduguri to Damaturu, Yobe State, where I would travel ahead of time and receive, but on the condition that I don’t let him return to Borno State. I gave them the money and rushed down to Damaturu, where I waited all day, but neither my son nor the soldiers who collected my money showed up.

“Sometimes, they would call me and ask for money to enable them to check for his file, or they would call and tell me that one of their bosses wanted to see me, and when we met for a rendezvous, they would make all kinds of promises to me and then ask for money.”

With time, she realised she was being taken advantage of.

“Years later, the Giwa Barrack was attacked by Boko Haram terrorists who broke into the detention facility, and I never saw or heard from my son again.”

Unknown to Hajja Gana, the military had transferred her son and other suspects to the Wawa Cantonment of the Nigerian Army in Kainji, North-central Nigeria.

It took five years for Mustapha’s family to learn about this transfer.

Life Without Mustapha

Three months after soldiers picked him up, Mustapha’s wife gave birth to their first and only child, Abdulkarim.

According to her mother-in-law, Nafisa continues to live with her husband’s family because she has never given up hope of seeing him again.

Supported by her husband’s mother, young Nafisat weaned her child, enrolled in the university, and eventually graduated. Her son, Mustapha, had to be fed with “lies” about his father’s whereabouts.

“We usually tell him that his father has travelled to Saudi Arabia and will soon be back,” Nafisat said.

But as the boy gradually matured, his demand for his father shifted from a child’s expectations of beautiful gifts from his daddy, who would “soon” return, to ask his mother to allow him to speak to his daddy through her mobile phone.

“Being a member of the women’s civil society network known as Jire Dole, I had the cause to take my grandson to some of our advocacy outings and meetings just to make a statement about how it was wrong to wrongly arrest and detain a people on false accusations of being Boko Haram terrorists, yet you don’t have any evidence to prosecute,” she said.

Those public engagements with his grandmother had inadvertently exposed young Abdulkarim to finding the truth about his father’s whereabouts.

“So, one night, he came to me and asked why the soldiers were detaining his father in the military facility, and I told him that the soldiers lied against him to keep him there,” his mother, Nafisat, said.

“Since then, Abdulkarim had resolved to be a soldier so that he would one day free his father.”

But he never gets tired of writing letters to the military commander on the need to free his father, whom he has never seen since birth.

“Each time I was to go out to attend any public function, Abdulkarim would ask if I was going to see any military commander there. If my answer were yes, he would run to get a piece of paper and pen and then scribble a letter for me to deliver to the military commander.

“I was very emotional the first day he handed me that piece of paper, and I cried all day,” Hajja Gana said.

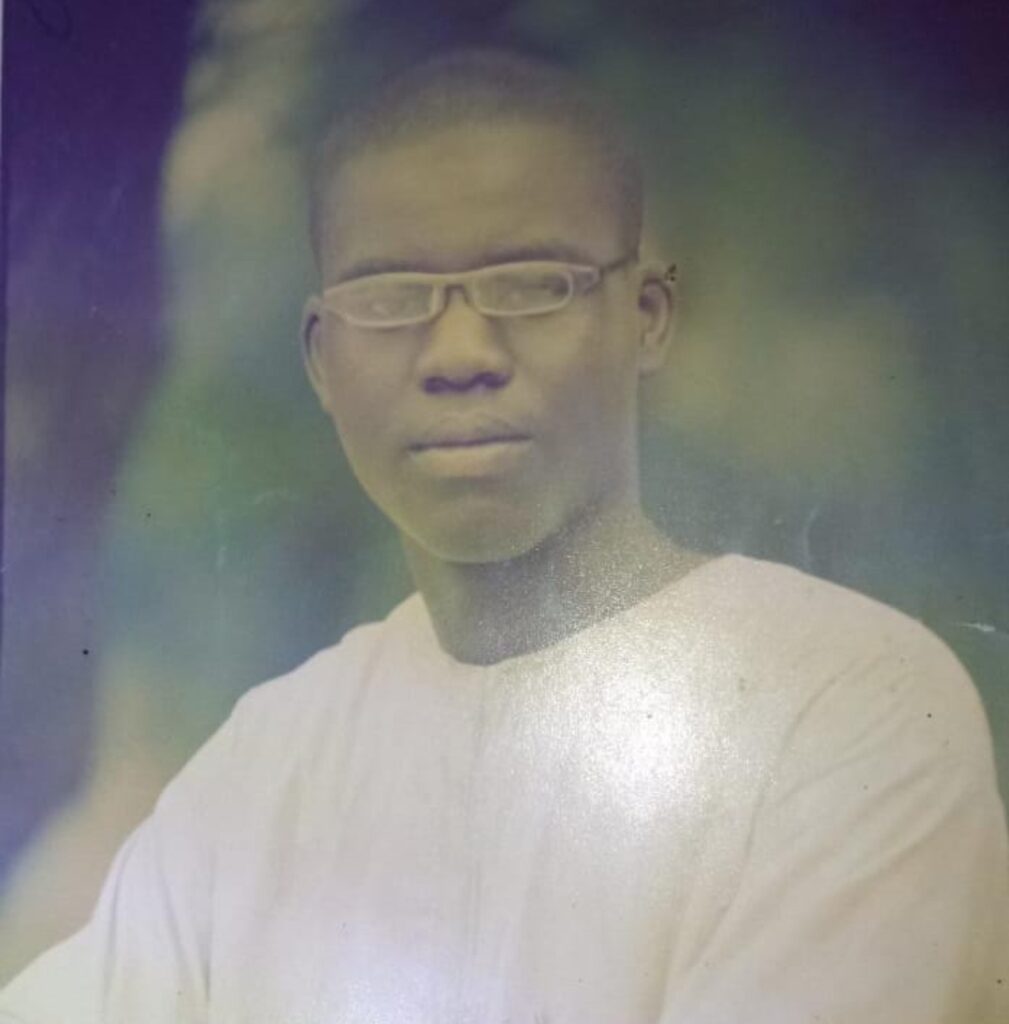

“It was then that I came to realise that it has already been ten years, and this boy has grown to be able to write a letter; yet he has never set eyes on his father, whom he only appreciates from what we told him and from viewing the old pictures we have of him at home.

“Abdulkarim is now in class 6, preparing very soon to go to secondary school, and I thank God for his life and the love and support I enjoyed from people who helped my family ensure that he goes to school.

“My heart bleeds whenever he says he wants to become a soldier. A child who was just six months old in his mother’s womb when his father was arrested and detained has joined us in seeking justice for his dear father ten years later,” she said in tears.

Abdulkarim’s Letter

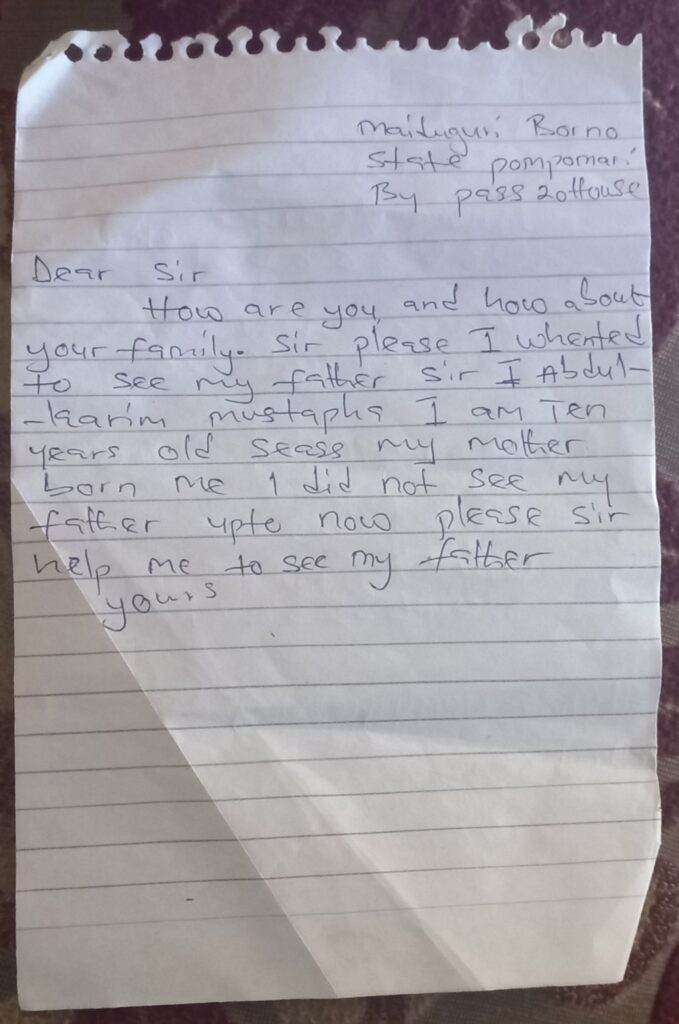

At ten, Abdulkarim’s letter and how he expressed himself defined his personality as a child who knows what he wants now and what he would like to do in the future.

His legibly scripted short letter reads:

“Dear Sir,

How are you and how about your family?

Sir, please, I whanted [want] to see my father, sir. I (am) Abdulkarim Mustapha.

I am ten years old.

Since my mother born to me, I did not see my father up to now.

Please, sir, help me to see my father.”

Speaking with this reporter, Abdulkarim shared his dream of becoming a military officer someday so that he could be able to free his father from wrongful detention.

Though Abdulkarim’s dream of joining the military to rescue his father may seem a far-fetched mission, the primary six pupils said he would continue to write his letter to the military authority until God answers his prayers someday.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter