A Database Of Donors Is Filling Blood Supply Gaps In Nigeria

The need for blood is constant in Nigeria, but there is a shortfall of about 73 per cent in its supply yearly. One initiative is organising blood drives and building a database of voluntary donors to fill this gap.

Oftentimes, when Adekola, 29, is experiencing an episode of sickle cell crisis, his doctor informs him that his blood count is low and he would need a transfusion. Adekola would then call his friends and family members, and almost immediately someone would arrive to donate a pint of blood and save the day. But on one occasion Adekola described as “critical”, no one was readily available to donate.

Adekola, who was diagnosed with Sickle Cell Disorder (SCD) right from childhood is still experiencing different shades of discrimination and stigmatisation that come with living with the disorder. For this reason, publicly announcing that he needed blood and stating why was the last thing he wanted to do.

“But I had to,” he said. “I posted it on Twitter, saying I needed blood donation, disclosing my genotype and blood group, and a lot of people shared the tweet.”

This single post began his relationship with Haima Health, an organisation with a large blood donor database across 14 states in Nigeria, and links them to patients in need. “They contacted and helped me find donors who were sent to the hospital,” Adekola said.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), Nigeria needs an average of 1.8 million pints of blood annually. Blood transfusions are a very common medical procedure. On average, one out of three people will need blood in their lifetime due to reasons ranging from accidents to unforeseen catastrophes, emergency hospital procedures, or life-long battles with chronic disorders such as Sickle Cell Anaemia.

As the demand for blood is constant, Nigeria’s National Blood Transfusion Service (NBTS) said the agency only collects 500,000 pints of blood every year with a shortfall of about 73.3 per cent.

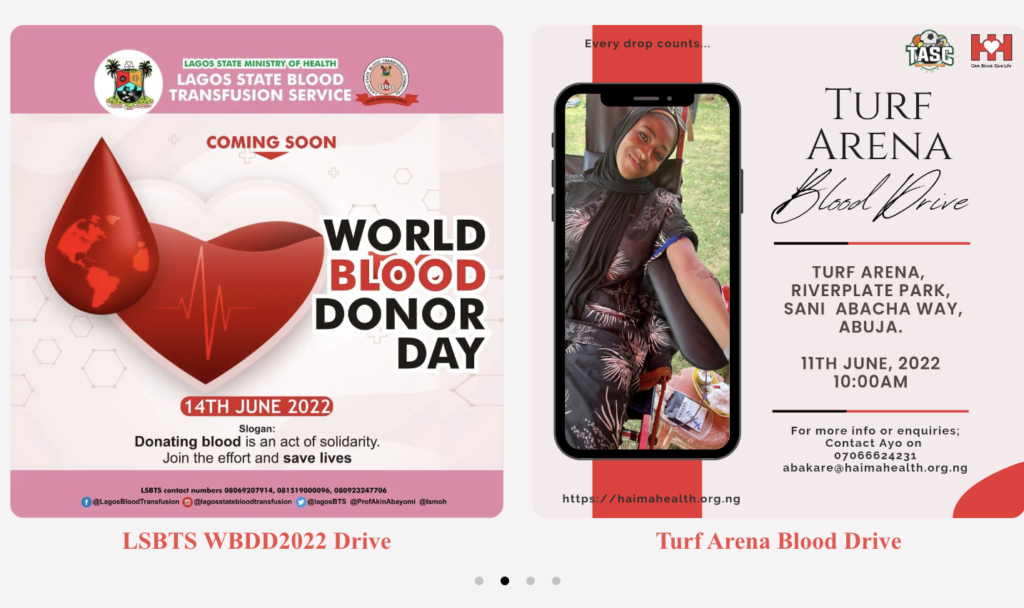

Blood drives and a database

In 2016, when Haima Health began linking blood donors to patients in need, Bukola Bolarinwa, the founder of the organisation, said donors were just people within her circle registered in a notebook, who were contacted to donate their blood when needed.

“It worked for a while, but obviously one can only donate blood once every three months,” she said, explaining that the registered donors they had at the time were quickly exhausted as the demand for blood was high.

Eventually, the organisation expanded their list of donors by setting up blood drives attended by larger numbers of people. “We began to work with churches and mosques, we worked with universities too. Sometimes we hold blood drives in National Youth Service (NYSC) camps,” Bukola said.

The NBTS does the blood collection process and the pints of blood are often kept at a blood bank. The role of Haima Health is to organise blood drives and collect information about donors, such as their blood groups and genotypes. This measure has currently established the biggest database in the country with over 2,000 registered voluntary blood donors.

“Creating a database is important to us because sometimes patients need fresh blood drawn within a day or two and if we focus on just the blood collected at these blood drives, it might not be suitable,” she explained.

Donating blood supersedes the act of giving out blood when it is needed. The latter process is often rigorous, and even when voluntary donors are contacted and directed to visit a hospital where someone is in need, there are various steps between extraction and transfusion.

Bukola explained that when a donor gets to the hospital, they are required to fill out a form that asks about their health history. “If it is a woman, the form asks if she is on her period, breastfeeding, or has not donated blood in the past four months. If it is a man, it seeks to know if he has not donated in the past three months.”

She added that things like weight are considered too. “You cannot donate blood if you’re below 55kg and sometimes even when you are overweight.” The screening process also includes checking for malaria, hepatitis, syphilis, iron levels, and haemoglobin levels.

Once a donor is fit to donate, the blood is collected with a sterile needle punctured into a large vein in the arm, linked to a tube that directs its flow into a plastic bag the size of a unit of sachet water, which fills up within ten minutes.

Although the donors from Haima Health’s database give out their blood for free, the patients are still required to pay for it before they are transfused because of the screening process. “The hospitals have to charge because even though the blood is free, it goes through processes to make sure it is safe for the patient, and all that comes with a cost,” Bukola explained.

The process protects the patients

From Adekola’s story, although Nigeria is among one of the three countries with the highest number of people born and living with SCD, there is a prevalence of stigmatisation that hinders care seeking from patients even during critical situations.

Adekola told HumAngle how, while growing up, his secondary schoolmates often made fun of him for always being sick. He said it went to the extent that they would calculate how many years were left for him to live. “One of them even predicted that I would not live till 21,” he recalled, laughing at the memory.

Even though Adekola has learned to be more open about his condition as an adult, he says the stigmatisation has not stopped. So when Haima Health sent him a donor without disclosing his information, he felt shielded and realised he preferred this method of getting assistance.

“Now I don’t need to start calling people and informing the whole world what I am facing, I can easily reach out to Haima and they will send a donor. They also have a database I do not have and I am comfortable that, no matter what, someone will be available to donate blood.”

Bukola Bolarinwa explained that when a donor is contacted, they are just given a name and the address of the hospital, including transport fare.

“Most times, it is not even the patient that contacts us, it is a family member or a friend that calls us and so our donors do not know the person in need and do not interact with the patient,” she said. The database is full of voluntary donors who willingly donate on their own and not for recognition or compensation.

Bridges the gap but not without obstacles

Haima Health helps fill in a huge void in Nigeria’s health care system. Bukola, however, admitted that challenges occur every day. One of such is the rising insecurity the country is currently facing that has made donors more conscious of the locations they are being sent to donate blood.

“Before, we would get a request at 9 p.m. and a donor would be on their way to Gwagwalada [an area council in the Federal Capital Territory 40km away from the city centre]. It was never an issue. But now when requests come late, we have to tell them to wait until the following day to get a donor,” Bukola explained.

Two years ago, it was easy to get people to donate to anyone in need at whatever hour, as long as the donor was available. Currently, the cut-off time for receiving requests has been set at 8 p.m., she said, adding that it is unfortunate as medical emergencies occur at any time.

Bukola listed the country’s deteriorating economic situation as another of the major challenges. “People who would normally be happy to donate now feel that they are managing themselves too, so how would they give out blood?”

She stated that these issues, although out of their control, have affected the overall turnout of voluntary donors even when they organise blood drives.

This story was produced in partnership with Nigeria Health Watch through the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter