With Nothing To Eat, Nigeria’s IDPs Settle For The Leftover Of Those Who Terrorised Them

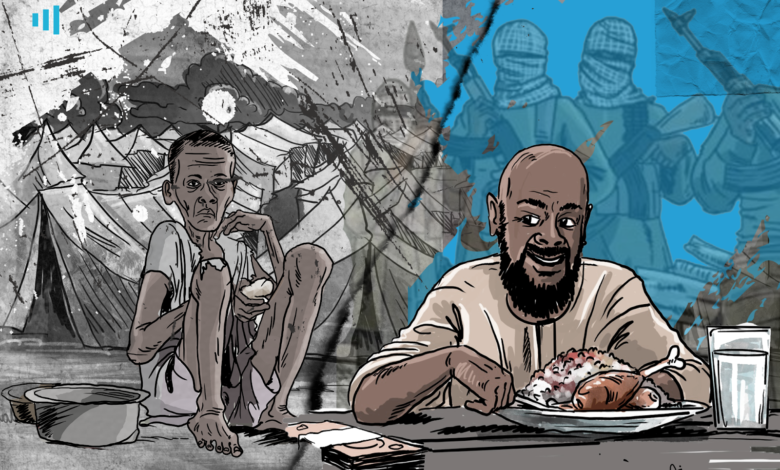

The abundance at a camp for former Boko Haram members contrasts sharply with the extreme poverty and hunger widespread among internally displaced people in North East Nigeria.

After over a decade of waging war in the name of religion, Abubakar* has (apparently) dropped his gun and thirst for blood. He joined the terror group Boko Haram as a teenager and has known only violence his adult life, but now he wishes to settle for a quiet life of trading with his wife and child. He is shocked by how well the Nigerian authorities have treated him, he says. At the transit rehabilitation centre known as Hajj Camp in Maiduguri, the Borno State capital, he gets a roof over his head, a mattress to lay on at night, a monthly cash allowance, and enough foodstuff for him and his family. The food supply is so generous that sometimes when they cook, they eat to their fill and leave remains. They then gather the leftovers, spread them in the sun to dry, and a day or two later sell them to someone who collects similar items from other former terrorists at the camp. Abubakar imagines that this material ends up with a farmer who will feed it to his livestock to fatten them.

He is wrong.

It ends up in the hands, pots, and bellies of internally displaced people who cannot afford anything more decent — the same people who were at the receiving end of Abubakar’s gun and thirst for blood.

For the first time since the Boko Haram crisis erupted in northeastern Nigeria over a decade ago, some events are taking place on such enormous scales. This is especially true of two things: the mass surrenders of insurgents who have been absorbed into a reintegration programme and the mass resettlement of internally displaced people from Maiduguri to their ancestral communities in other parts of the region. Interviews with the beneficiaries of both programmes, however, betray a disparity in how the government implements them.

On the one hand, the state authorities are cutting off access to humanitarian aid for IDPs to force them to fend for themselves, even though the widespread operations of terrorists render such efforts life-threatening. On the other hand, more resources are invested in rehabilitating former terrorists with the expectation that this would bring a quicker end to the conflict. Many observers believe such a paradoxical arrangement could fuel grievances and obstruct the path to peaceful coexistence in the future.

Isa Kamsulum had just mentioned something about the lack of adequate housing at the resettlement site in Shuwari when he remembered something else.

“People don’t have money to buy normal food,” he blurted, his voice rising sharply to underline the seriousness of the situation he was describing. “So they buy this dried food. Vendors bring it here from prison and other places.”

This trend started last June. The dried food he was referring to is called biri gamda, a type of animal feed made from meals prepared with rice, corn or millet flour. He explained that since a measure of maize was ₦1,300 and people who engaged in manual labour earned no more than ₦1,000 after the day’s job, the IDPs could not afford regular foodstuff. They are forced to opt for alternatives like biri gamda, which is cheaper but also unhygienic. The process of drying exposes the food to insects, reptiles, and dirt. Another source of the biri gamda is food that is stuck inside grinding machines and has probably gotten mixed up with oil.

Two kilograms of biri gamda are sold for ₦500 (60 cents) and should be enough to fill the plates of one small household for a meal. The fact that it is traditionally meant for animals has not discouraged IDPs from scrambling desperately for it. “The last time, the vendor came with seven sacks. Before he even opened his shop, he had already sold five of them,” recalled Isa.

When I visited Shuwari just before sunset in the first week of September, the vendors had almost exhausted their stock of biri gamda for the day. One only had grains and a few pellets left. He had bought a small sack earlier from Hajj Camp with ₦4,000. I picked a stone used to hold the sack in place to confirm that it was truly a stone, as it looked very much like the foodstuff next to it. The vendor previously traded rice, maize, guinea corn, and beans, but as people could no longer afford those, he had to switch to something else. As he spoke, two boys grabbed at what was left of the biri gamda. One of them, no more than 10 years old, placed them in an aluminium bowl and snacked on it a few meters away. The second boy folded his oversized t-shirt into a pouch, put his dinner inside, and hurried off. The vendor was not going to charge them.

A man sitting under the shed grabbed some of the pellets for himself, too, and ate with a straight face. If you looked close enough, you would see the glint of a smile. He was not enjoying it, the vendor clarified. “It’s because he’s hungry.” The man stood up, eager to tell his story. His overflowing babban riga , a bulky traditional attire worn by men in the region, did not do much to cover his gaunt frame. He had become hypertensive and could no longer work, he said. So, every day, he would sit by the road to beg for alms. Sometimes, he got some. On other occasions, like today, he was not so lucky. As a result, he did not have money to buy a substantial amount of top-quality biri gamda and had to settle for what was literally the leftover from the leftover.

The second vendor still had a lot of biri gamda when I visited. He buys from merchants at the Customs Market in town, who in turn got their goods from Hajj Camp. Sometimes, he buys from the Borno Maximum Security Prison or people selling animal-fattening materials at the local Cow Market. He started the day’s business with five sacks, but what remained was less than one. Two old men crouched beside him to each buy two kilograms worth of the material. The pellets were a mixture of millet, maize, and rice — a combination that was unthinkable for regular food. “This is a good one,” the vendor said, smiling and shaking a fistful of biri gamda. And it is true; what he sold looked healthier than what was available at the first shop.

The people interviewed at the resettlement site declined to give their names because they feared the government would get back at them for protesting their conditions. “But at least now you have seen it with your own eyes,” one of them suggested.

Oluwagbenga Sadik, a nutrition policy analyst, said the consumption of biri gamda by IDPs is dangerous for several reasons. One, because it is not intended to be taken by humans, its production does not follow basic food safety guidelines. In addition to this, the population taking the biri gamda is assumed to be at risk when it comes to severe levels of malnutrition.

“This means their body is susceptible to infection and their immunity is low. Now, if you subject these people to high food safety risks in addition to malnutrition and at that scale, it becomes a public health issue,” he explained.

Another concern, according to Sadik, is psychological.

“This is a food that is traditionally meant for livestock, which means even if it were very nutritious — which it isn’t — you would not find people consuming it unless they had no other option. And this is very concerning because cultural attachments to food also contribute to our well-being. It speaks to high levels of degradation.”

The destitute situation of the displaced people in these places contrasts sharply with life for Boko Haram fighters who surrendered to the Nigerian authorities and are being prepared for reintegration.

Nigeria openly started reintegrating Boko Haram deserters in 2016 under a programme called Operation Safe Corridor (OSC). The goal is to reduce the manpower of the terror group and offer insurgents an attractive alternative. So far, over 2,100 “clients” have successfully passed through the programme.

Meanwhile, a huge crisis broke out in the local jihadist scene in May 2021, when the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), which had broken away from Boko Haram, invaded the Sambisa forest stronghold of Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihād (JAS), the faction led by Abubakar Shekau. Shekau died, and many of his followers opted to desert rather than join ISWAP. The result was an unprecedented wave of surrenders. Nearly 52,000 people gave themselves up to the Nigerian government within a year, including 13,360 people identified as combatants.

The OSC programme lacks the capacity to take in all the deserters, and so the authorities devised another scheme. The Borno state government now manages three camps where it keeps Boko Haram deserters for some months before releasing them into society: Hajj and Shokari in the state capital and Bama Local Government Area.

One estimate given to us in September was that men at Hajj Camp numbered over 4,000, while women and children were about 11,000. There are still new arrivals, but the frequency has reduced. Officially, the former insurgents are supposed to be housed in this place for up to six or seven months. Sometimes, people complain and are discharged within four months. Occasionally, they are kept for longer periods.

We learnt from residents that the treatment of ex-combatants depends on their marital status. Those who are unmarried eat in the central kitchen and receive a monthly allowance of ₦10,000 ($13). The married ones, like Abubakar, receive a monthly food supply that includes 50kg of maize flour, 25kg of rice, 2 litres of oil, 1 sachet of seasoning, 1 sachet of salt, and ₦5,000 to buy charcoal. They also receive the ₦10,000 allowance while their wives are given half the amount. Those with multiple wives receive double the food supply.

“The day we arrived, they gave us five yards of clothes, plastic mats and mattress, ₦3,000 for shaving, and blankets. They gave us a room. In the morning, they gave us rice as breakfast, and in the night, they gave us maize flour,” said Lawal, another former insurgent who surrendered sometime in April. He’s not certain of his age, but he does not look any older than 20. He confirmed that the food served in the kitchen is sufficient, “with even leftover sometimes”.

Occasionally, when the foodstuff is not supplied on time — maybe there’s a delay of a few days to one week — the ex-terrorists would protest.

One disadvantage of the distribution system, according to Abubakar, is that it favours those with few children, such as him. Residents with a wife and multiple children receive the same amount of food. So, while the supply easily lasts his family for more than a month, other households struggle — especially when they sell the food to get money for other things, such as fish and meat, after exhausting the cash allowance.

The animal feed that IDPs have now resorted to eating comes from excess food at the Hajj Camp.

Abubakar says those who eat in the central kitchen rarely have surplus food to turn into biri gamda, unlike family men like him who cook more than enough from time to time. Since they have no one to give the food to, they place it on top of sacks in front of their tents and leave it to dry. They then sell it to people “who want to use it for animal fattening”.

“We sell it for ₦50 or ₦60 per kilogram. But because it is now rainy season and it takes time to dry, the price has gone up to about ₦150,” said Abubakar.

Across the camp, 15 to 20 sacks of biri gamda are gathered every few days. Some people among the camp residents buy from the various households and then resell to vendors on the outside.

Asked if he was aware those sacks end up being sold to people who eat the leftovers, Abubakar replied that he wasn’t, nor did he ever imagine that could be happening. Lawal, too, insisted that the people buying it must be giving their livestock.

Several factors are responsible for the impoverishment of the internally displaced people. Three of the major ones are the suspension of humanitarian aid by the Borno state government, astronomical food inflation across Nigeria, and frequent attacks by terrorists in areas farmed by the IDPs in Borno.

The authorities accuse displacement camps of encouraging prostitution, drug abuse, and unchecked childbirth. They argue that the aim of the resettlement programme is to restore the dignity of displaced people and to build their resilience such that they can earn their livelihood through agriculture and would no longer have to rely on aid. The only problem is the farmlands and forest areas on the outskirts of the town, which are the only ones available and vast enough, have become more unsafe since the mass surrender of insurgents. This may be partly due to the splintering of the terrorist faction formerly led by Abubakar Shekau, who is now late.

Ahmadu Aga, a community leader at the Muna Elbadawi camp in Jere, recalled that it started with Boko Haram terrorists seizing food from farmers two years ago. Then, they started shaking them down for valuables such as mobile phones. Then, they started abducting them for ransom.

“For the nine years we have been here, this year is the worst,” said Ahmadu, who is fondly known as Ba Wakil. “So many people have been taken. From our community alone, more than 30 people have been abducted this year. There’s too much hunger and starvation.”

The Muna displacement camp is managed by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA), but Ba Wakil said they last supplied any aid in April. Before that, they donated foodstuff to the IDPs every month.

Many IDPs complain of not having food to eat for several days at a time. They are faced with the dilemma of staying at the camp, which is safe from terror attacks but not from starvation, or going to the farmlands, where they might get some sustenance while risking death or abduction.

The kidnappings have become so frequent that the displaced people were forced to start a committee to crowdsource ransoms. People contribute from the little they have — ₦50, ₦100, ₦50, ₦100 — in hopes that others will reciprocate their gesture when they also run into the terrorists’ jaws.

“It’s been three years since we were resettled, but there’s been no help from the government or NGOs,” lamented Isa. “People are hungry and begging people to feed their children. Children have become malnourished.”

He told the story of one man who went to the farmlands in search of work as a labourer, but he was not fortunate to get any. He then sold his hoe just so he could return to his family with some food.

Despite worsening poverty among IDPs, the state government plans to double down on its resettlement strategy.

“On the assumption of duty, I promised the people of Borno State that I’d close all official camps that are inside Maiduguri Metropolitan Council and we did so with the help of Almighty Allah,” the governor, Babagana Zulum, said in October. “Now my next agenda is to see how we shall close all the IDP camps that are in the local government areas without which there shall be no peace.”

When we shared the complaints with Director-General of the Borno State Emergency Management Agency (SEMA), Dr Barkindo Saidu, he confirmed that the agency took food items to the IDPs at the Muna camp in the first week of November following HumAngle’s visit.

He explained that the delay in the provision of aid from NEMA was because the federal agency was waiting for the approval of funds — though formal displacement camps managed by the state government experienced similar suspension of aid months before their resettlement.

The SEMA Director-General said he was not disputing the struggles the IDPs are facing but lamented their continued reliance on humanitarian support. “For somebody to stay for 13 years in a location without finding a means of livelihood … honestly, the issue of taking care of them is not sustainable.”

He mentioned that the government provided 52 buses to take people to their farms and agro-rangers were escorting them to their farms, which means “anyone who is not lazy” could farm. He added that the government is in the process of giving reasonable business grants to the displaced people so they can become self-reliant as they are resettled from the camp. This, he said, should be finalised by December.

“We will continue giving them succour. They should be patient. As we have been considering them, we will continue considering them. For those who can find a means of livelihood, we are encouraging them to find any vocational or income-generating activity.”

When we talked to Abubakar in September, he had spent nine months at Hajj Camp and was eager to leave despite the fine treatment. His eagerness might have something to do with the lump sum they are given after the programme to support their reintegration.

The government gives ₦100,000 ($125) to married men and ₦30,000 to their wives. It gives ₦70,000 and some foodstuff to unmarried men.

Many IDPs who were recently resettled, however, did not receive this much support. Usually, the authorities gave ₦50,000 to men-led households with the promise of paying the same amount after they had moved to the new location. However, many IDPs did not get that second payment.

When the government sent them packing from the Farm Centre displacement camp in Maiduguri in December 2021, Isa said it gave people from Bama two options: return to Bama or move to Shuwari. Eventually, “only those from Kalabalge were paid when they went to their local government area. Those of us from Bama and Gulumba were told to get shelter in Shuwari and then they would take us to Gulumba for our balance. But we didn’t get it. Those from Jere, too, didn’t get their balance.”

Again, there’s limited housing in Shuwari, and those like him who are not native to the area were not allocated any. Hundreds of households were forced to put up tent-like structures again, just like in the camp. Isa noted that one disadvantage of this was that occasionally, when aid was distributed, it only went to those assigned government houses.

Asked about the disparate treatment of IDPs and former insurgents, SEMA Director-General Dr Barkindo said the rehabilitation programme for Boko Haram deserters was to ensure they embraced peace.

“It is better we encourage them to come out so that we can get more space for farming,” he told HumAngle. “The Boko Haram (members) are just coming. We will not retain them for more than a year or so, just like the IDPs. Once we have studied them and see that they are reformed, we will also stop giving them food.”

It is not clear how much resources go into sustaining the rehabilitation camps for ex-terrorists. The Borno state governor revealed last year that his government secured €15 million from Berlin while speaking about the repatriation of refugees and reintegration of insurgents. Former Vice President Yemi Osinbajo also confirmed that the government was partnering with donors when he told the deserters: “We will be working with you and with the state government as well as donor agencies and friends to ensure that we are providing you with not just income, but a place where you can settle down with your families and do your work and your businesses.” According to France24, the United Nations, the European Union, and the British government have all pledged their support for the programme. During a visit to Nigeria in May 2022, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said he was “fully supportive” of plans to expand the reintegration facilities. The Borno state government is looking to raise $150 million for that expansion.

However, in spite of all the money pumped into it at the expense of displaced people, the programme’s effectiveness in reforming the minds of the former Boko Haram members is doubtful. The term “repentant Boko Haram” is often used in the media to refer to the deserters, but many of them have admitted that the major push behind their surrender was the crisis that broke out following the death of Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau — not regret about their actions.

HumAngle’s assessment has shown that the government-run programme is not doing a lot to evoke this sense of regret. Abubakar says they spend most of their time being idle. They lounge in their tents. Some of them with small businesses go to the market to buy goods to sell. “We don’t do anything. People stay, sleep, wake up, and visit others.”

But sometimes, on Wednesdays, clerics are invited to address them at the mosque, and whoever is interested can join them.

“They preach to us that our former doctrines are misconceptions, our understanding of jihad is false, and we were astray,” Abubakar said. He added that the sermons do not cause people to grumble or argue, but he cannot tell what is in their hearts and whether it had any impact on them.

Lawal did not seem to know about the Wednesday sermons. He said nobody had come to preach to them since he arrived months back, except the very previous Wednesday — suggesting that the activity was either not frequent or not everyone was engaged. Neither of them mentioned any other attempt at disabusing them of their radical beliefs.

The sermons might have had some effect on Abubakar, though. He says he has learnt that what they did was not good, and he feels bad. He adds that when you leave fighting behind you and rejoin a people, you should accept their way of thinking. But it is still obvious he is sympathetic towards Boko Haram. He tries to distinguish between harm inflicted by law-abiding members of the terror group and that from rebellious elements.

“You know there is fai [seizures taken from enemies]. Some, with the knowledge of their leaders, attack people and receive their properties. But even there in the daulat [Boko Haram-controlled territory], we had criminals who attacked people without the knowledge of the leaders. We see those people as bandits.”

Governor Zulum himself was sceptical about the OSC deradicalisation programme before the mass surrenders, describing it as ineffective and favouring speedy court trials instead.

Another flaw with the state government’s programme is that the screening process is not airtight. The camp is meant to hold combatants and other members of Boko Haram, not those who simply lived in areas governed by the group. The assessment is done by a group led by Retired Brigadier General Abdullahi Sabi Ishaq, who is a special adviser to the governor on security affairs, with members including former insurgents and officials of the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF).

Abubakar, however, noted that many Boko Haram fighters were allowed to leave the camp after a few days because no one exposed them — a claim corroborated by the France24 report.

He also observed that people suffering from trauma have no access to counselling, and the camp authorities only opened a Qur’anic school for children after there were complaints.

There are fears that the unequal treatment of Boko Haram deserters and IDPs may cause existing tensions among victims of the insurgency to reach a boiling point when the two groups inevitably return to the same communities.

For example, several displaced women have complained to HumAngle in the past about the government’s double standards of releasing confirmed Boko Haram fighters while continuing to detain their husbands without trial, even though they were arrested arbitrarily.

Tijjani Modu, a peacebuilding expert based in Maiduguri, believes the absence of transitional justice for victims of the insurgency could lead to a state of “post-crisis conflict” and says he has already started seeing the early warning signals. According to him, it is not enough to build houses for the resettlement of IDPs, especially considering the trauma they went through and the scale of their loss, involving both loved ones and properties.

“If you can kill my father and brother and burn my house, now the government is saying you have surrendered and repented and the government supports you with ₦1 million or ₦100,000 to come and stay with me, but me whose parents you killed, you cannot apologise to me. And they want me to stay with you?”

Modu stressed that the former insurgents would not be accepted if justice is not done to all, both the victims of the insurgency and the repentant combatants. “Now people are afraid of the military. But some years to come when the military return to their barracks, it [ill feelings against former insurgents] would definitely burst out,” he said.

But Abubakar does not think he has anything to worry about. One, he joined the terror group as a teenager, and except for his family, not many people know his background. Two, he has seen many of his associates visit their relatives and mingle with people in the communities without incident. He himself has gone to his hometown for a few days.

“People don’t usually stigmatise,” he said. “And even when you see that they are sad or annoyed, they don’t openly express it. We stayed with them; we went to visit our families here. Nothing happened.”

As Abubakar walks freely on the streets of Maiduguri and looks forward to a prosperous future with the help of the government, his former associates in the bush continue to terrorise displaced people in Borno, flooding their hearts with fear and squeezing life out of them — again, technically with the help of the government.

I asked Ba Wakil why people still go to farm and fetch firewood on the outskirts, knowing the dangers that lurk in these places. His answer was simple.

“If you are lucky, you will return and get your food. If you are kidnapped, we will raise money and send for your release.”

“But if you don’t go, what are you going to eat?”

*The names of the former Boko Haram members interviewed for this article have been changed to protect their identity.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter