Why Terrorists Are Moving Into Kano Villages from Katsina

For terror groups displaced by military operations or peace pacts in Katsina State, North West Nigeria, the temptation to expand into softer, less militarised neighbouring territories like Kano State is very high.

For years, the commercial hub of Kano stood apart in the insecurity-ravaged northwestern Nigeria. It is a state often spoken of for its relative calm. Its borders touch troubled territories of Katsina State, yet its interior remained mostly insulated from the daily terror that has become routine in neighbouring states.

But that illusion of distance is collapsing. Kano is facing terror attacks.

One recent attack was on Monday night, Nov. 24, in Biresawa, a village in Tsanyawa Local Government Area (LGA), in which six women and two men were reportedly abducted by terrorists who stormed the village. More people were said to have been abducted along the way.

“We received reports that they entered the towns of Biresawa and Sundu in the Yangamau ward, and they also abducted some people in Masaurari in the Yankamaye ward, all in Tsanyawa LGA last night,” posted Sani Bala on Facebook, a member representing Tsanyawa/Ghari at the House of Representatives.

Residents claimed that a warning came before the terrorists’ arrival, so they informed the police and the military. “They gave us their numbers and asked us to call if we got any additional information,” Kabiru Usman, a resident, said. However, the operatives didn’t arrive on time.

Local vigilantes who spoke to HumAngle said the residents attempted to counter the terrorists, but they were overpowered, and the terrorists ran into the edges of Katsina with some of the kidnapped victims.

“We are living in constant fear,” said Alhaji Jibrin, a resident of Tsanyawa. “Some people have already moved to Bichi, and others have scattered to somewhere safe.”

Across Tsanyawa and Shanono, the fear of a terrorist invasion from Katsina has already overwhelmed many residents. Katsina has been a reference point for violence. Villages have been emptied after repeated raids, farmlands abandoned, and markets shattered by fear.

Now, villagers in Kano fear they are witnessing the same pattern unfolding across their homes, farms, and footpaths.

The geography of fear

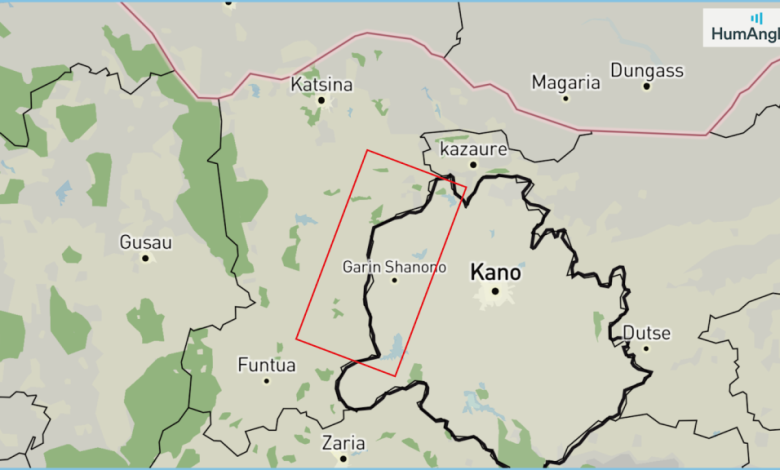

The security crisis in northwestern Nigeria has always been an ecology of movement; one of armed groups, displaced families, and ungoverned spaces where the state is heard but not felt. From the forested belts of Safana and Batsari in Katsina, groups have gradually pushed southwards and eastwards, exploiting porous borders between LGAs and the vast, unpoliced farmlands that serve as both routes and hideouts.

The boundary between Katsina and Kano is not a wall; it is an open field traversed daily by farmers, traders, herders, and, increasingly, armed groups who use the cover of night to slip between territories. Villagers in border communities have long observed that the terrorists who attack them vanish across these invisible borders the same way they came.

Through interviews with residents across Tsanyawa and Shanono, HumAngle gathered a common description of attackers arriving in groups of 10, 30, or 50, on motorcycles moving with an ease that reveals familiarity with the terrain. They started with targeting isolated villages, then moved to attacking towns and markets.

“Abductions in Shanono are not a new threat,” said Musbahu Shanono, a resident. “They started about three years ago, but the situation has become much worse now, especially since the beginning of this year.”

The former governor of Kano State and a former Minister of Defence, Rabiu Kwankwaso, has blamed the recent web of attacks on the unofficial peace deals Katsina communities continue to enter with the terrorists, who then move to Kano to wage attacks. “These bandits come from LGAs in Katsina, enter Kano to commit crimes, and then return to Katsina,” he said, describing the “peace deals” as reckless.

A crisis unfolding in slow motion

“We used to hear these stories from Katsina,” Jibrin Tsanyawa told HumAngle. “Now, when night comes, we sleep in fear.”

The attack in Biresawa is one of a growing list of recent attacks. Villagers speak of increased sightings of strange men moving around in the community’s farmlands. Farmers are beginning to avoid sections of their land that they once walked freely on. The market in Shanono now closes slightly earlier than usual.

The signs are subtle, but they add up; the way insecurity always does.

The Kano State Government has been eager to demonstrate its concern over the insecurity. Last week, the governor commissioned security vehicles and motorcycles, distributed across different commands to improve mobility and rapid response by the Joint Task Force in the state.

But rural residents insist that, despite the shiny vehicles and televised launch events, security presence remains thin on the ground. Many of these communities lie several kilometres from the nearest police or military outpost, and when distress calls are made, help often arrives long after the attackers have departed.

“It is not that security agencies are unwilling; it is that the geography itself defeats them,” said Musbahu. “To protect these areas effectively requires more than patrol vehicles; it requires intelligence networks, local collaboration, early warning systems, and most importantly, enough personnel to sustain presence.”

Even then, the attackers have one advantage the state lacks: they are not tied to any location. They move, regroup, adapt, and reappear. The state, meanwhile, is expected to stay rooted in every village, at every hour, with limited resources.

Security analysts have long warned of a potential insecurity spillover into Kano. Unlike some of its neighbours, the state possesses several characteristics that make it strategically attractive to armed non-state actors.

These characteristics include vast rural margins bordering Katsina, thick farmlands and forest patches that provide temporary shelter for armed groups, and thriving markets where stolen goods can be quietly absorbed into existing supply chains. These conditions are compounded by a lingering perception of Kano as inherently safe, leaving many communities unprepared for sudden threats.

For groups displaced by military operations or peace pacts in Katsina, the temptation to expand into softer, less militarised neighbouring territories is very high.

Kano, once considered a relatively safe area in northwestern Nigeria, is now experiencing an increase in terrorist activity, with recent attacks leading to abductions and a rise in fear among residents. The boundary between Kano and the troubled Katsina State has allowed armed groups to exploit porous borders and unpoliced farmlands to move and carry out attacks. Despite efforts by the Kano State Government to enhance security measures with new vehicles and resources, the challenges of geography and insufficient intelligence networks have hindered effective protection.

Local vigilantes and residents have noted the ease with which attackers navigate the terrain, indicating a familiarity with the region that poses further problems for security forces. It's suggested that unofficial peace deals in neighboring Katsina have contributed to the migration of terrorists into Kano. Security analysts caution that Kano's vast rural borders, fertile farmlands, and active markets make it a strategic target for armed groups, highlighting the need for better intelligence collaboration and increased personnel presence to secure the area effectively.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter