When Witchcraft Accusations Are Loud Enough, People Get Burned To Death

Losing your life in Nigeria’s Benue state can be as simple as getting labelled a witch, even in the absence of evidence. Those who survive the mob trials often suffer stigmatisation, injuries, and a seemingly unquenchable thirst for justice.

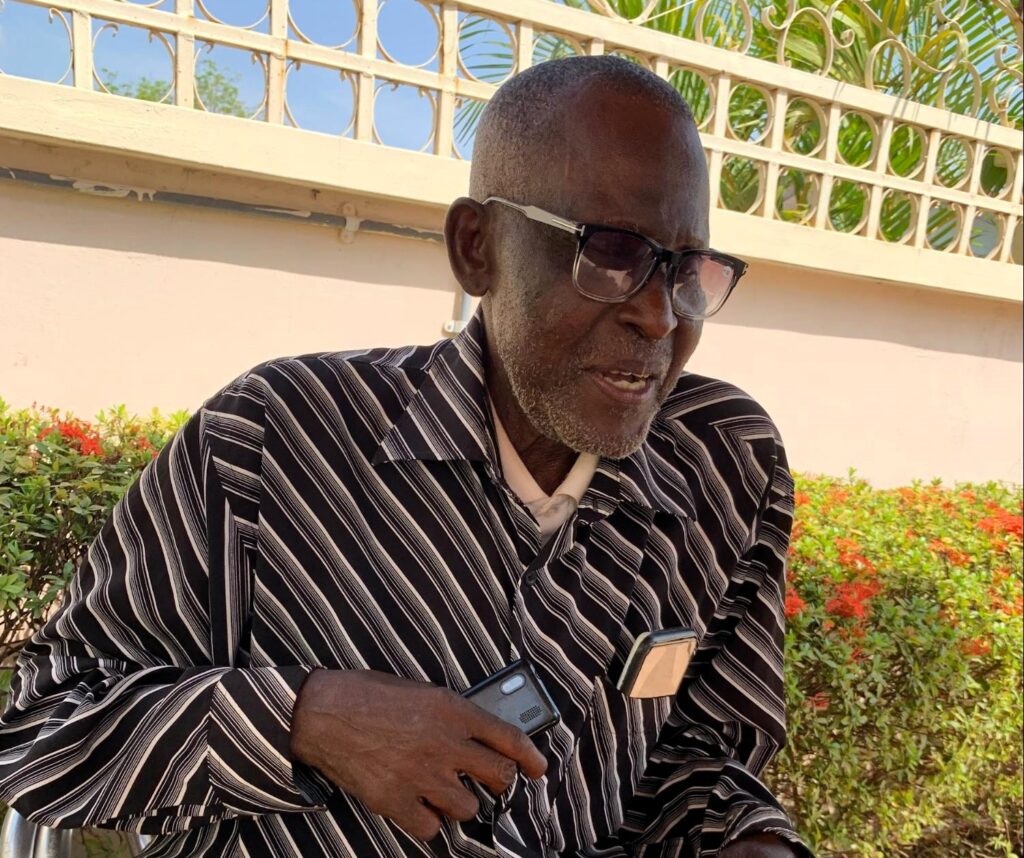

Though Justin Kyadoo looks nothing like it now, he had been a soldier once. During that time, he had gone on a rescue mission in Liberia and served the Nigerian military in Enugu, Calabar, Lagos, Jos, and some other states in Nigeria’s north. Many times, he came as close enough to death as any soldier can be. Yet in all of those times, he was not as helpless as he felt last year when he was accused of witchcraft and tossed by a raging fire.

The day was Jan. 13, 2023, and Kyadoo was away at the hospital when a group of young men, their motorcycles rumbling and raising the harmattan dust, came to his home in Gwer East Local Government Area (LGA) of Benue, North-central Nigeria, asking to see him.

Upon his return, the men, numbering ten, all between ages 20-23, informed him his presence was needed in the village but wouldn’t say more. When he asked for some time to eat first, they said they already had food waiting for him at the destination. The young men were quite convincing, and Kyadoo is quite old — 79 – sometimes needing to be repeatedly told something for comprehension.

When they got to the village, there were even more young men of about the same age waiting by a giant fire, which they fed with wood logs.

“They told me this [the fire] is the food they prepared for me,” Kyadoo remembers.

They held him still and, as butchers would do to a goat being led to slaughter, tied his hands and legs together and immediately tossed him by the fire.

“Even if it is a goat that you want to burn, you have to kill it first before setting it on fire,” Kyadoo said to explain how dehumanised he felt.

The young men were all members of the same age grade under which they regularly held meetings known as Bakwa; one of their members had taken to some terrible illness that wouldn’t go away, and an elderly member of their community had pointed to Kyadoo as the cause of the illness, hence the actions of the men.

Dooyum Ingye, the Benue State Director of the Advocacy for Alleged Witches (AfAW), tells HumAngle that accusations such as this are quite common among people in the state who believe in the existence and power of witchcraft.

Ingye’s organisation, founded in 2020, strives to see that public lynching, murder, and verbal witchcraft persecution are all things of the past.

“Our people believe there is a spiritual meaning to almost everything that happens anywhere and to anyone,” he explained.

Kyadoo’s daughter, Anne Sewuese, learned of the attempts to lynch her father a few hours after the young men took him.

Living in Makurdi, the state capital, with her husband and children, Anne could not immediately intervene physically to save him, so she sent security agents to the scene. They returned at 2 a.m., saying they had been overpowered by the mob consisting of about 80 people.

When the day dawned, Anne ran to the Police headquarters in Benue to complain. The authorities sent members of the E Division to Mbaivur.

Upon arriving at the spot, they found Kyadoo sprawled on the ground, having been left for dead by his torturers, with burns on the side of his stomach and both his hands.

The old man was taken to the hospital in a bid to save his life, but even there, his life remained in danger.

“Those guys were bragging about killing him. They said they thought they had finished him that day but that since he was still alive, they would come to the hospital to finish him off,” Anne said, her face reflecting the pain she felt.

Their threats, it would turn out, were far from empty because, on three different occasions, one of the men charged into the hospital, intending to attack Kyadoo. It was at that point that Anne formally reported the case to the Police, and they commenced arrests of the culprits.

The arrests of people around the village drew some dust and the attention of the village chief. Later on, it was found out that the young man whose ailment was blamed on Kyadoo was HIV positive and had been critically ill because he refused to be on his medications.

“They later confirmed that the guy has started taking drugs and is very okay,” Anne said.

Out of all the young men who accused Kyadoo of witchcraft and attempted to kill him, only six were identified, arrested, and jailed for about three months.

Currently, they have been released while Anne has pushed the case in court amidst pleas from them to withdraw.

“The only way I would want to consider withdrawing the case is if they [the six men] write an undertaking stating that they will be held responsible for any harm that comes to him,” Anne told HumAngle.

Even though the incident took place a year ago, and the gory burns from that day are all but scars now, Kyadoo carries one wound in his heart, which he says will never be healed.

When asked what would bring him some measure of peace, he firmly replies, “Firing squad.”

While Kyadoo may never get the closure he desires, Anne says she is satisfied with what she has been able to achieve with the arrests, jailing, and ongoing court cases she has built against her father’s attackers because it has instilled fear that will serve as a deterrent to others in the village.

She recalls a recent encounter she had with a man whose father was accused of witchcraft.

“He saw me by the roadside yesterday, stopped, and said, ‘Kai! Sister, I am so impressed by what you have done because when they burnt my daddy, and he died, I said one day, they will touch somebody that will warn them.’”

“They had been burning people in that village,” Anne said, explaining that even though some of them genuinely believed in the existence and power of witchcraft, they were also prone to making baseless accusations out of spite.

Ingye of AfAW confirms this through his personal experience growing up in Benue State as well as his experience doing advocacy under AfAW. “Accusations are driven by personal vendettas or conflicts within the community,” he said.

This was the case with 62-year-old Nathaniel Ijih, who was accused of causing the death of his now-deceased younger brother through witchcraft.

Personal vendetta

Ijih’s brother died in January 2023 of some illness that started after he went to the hospital to get his teeth pulled out. Before his death, there had been some disagreement within the extended family over the intended sale of a piece of land left to them by their dead father.

The death marked the beginning of Ijih’s woes because his sister-in-law accused him of killing her husband through witchcraft.

Ijih did not imagine that his troubles would get heavier than they already were, but they did; less than a week after an argument at a family meeting where he called out a man named Abeni, Abeni orchestrated a gathering that nearly cost Ijih his life and that of his 13-year-old daughter, Blessing.

Just like Kyadoo, Ijih and his daughter were tricked into attending their ‘interrogation’. It happened at about 1:45 a.m., Ijih said. Two persons came to his house, telling him his presence was needed at a meeting of the elders.

“[They said] I should go with my daughter, and I did, not knowing what they were planning,” he told HumAngle.

Many others were waiting, and an open fire was fed with firewood in preparation for their arrival.

The place turned out to be the compound belonging to Abeni’s father. There, Ijih was told he and his daughter had killed his late brother through witchcraft, and his daughter was seized.

“They asked my daughter, and she said she knew nothing about it. They sat her very close to the fire,” Ijih said, wincing now from the memory of that night.

Ijih was as confused as he was helpless. He had been accused before of killing his brother but had never heard a whisper about his little girl.

“On that very night, I asked Abeni why he said I killed my brother before and is involving my daughter now,” Ijih narrated, explaining that he was further down from the fire and that his daughter was the only one made to sit close to it.

His questions did nothing to change Abeni’s mind or that of the other people who had gathered for the ‘interrogation’.

That night, the mob consisted of about 30 people who believed that he and his daughter were witches, and between Ijih’s family and the crowd, not much could be done to save Blessing. With time, the little girl knew too that neither pleas nor the truth would save her.

Barely inches away from the fire, Blessing was dangerously close to death as any unguarded movement backwards would see her falling directly into it.

“After some time, she accepted having a hand in it so that they would spare her life,” Ijih said, explaining that they allowed her to leave the fireside after the fear-induced confession.

By the time the gathering dispersed, it was about 7 a.m. All those hours Blessing had endured by the fire caused a burn that tore open the flesh on her buttocks.

Ijih says there were simultaneous outcries of pain and sadness in his household that morning when Blessing showed her injuries.

“You see, as I am trying to say this, I am nearly shedding tears,” he said. “But as an old man, I cannot cry over that thing,” he continued, trying and failing to put up a strong front.

Ijih took his daughter to the hospital and then reported the matter to the Police. Subsequently, AfAW got involved.

Justice is often complicated

Even though it is clear as day that the rights of Ijih and his little girl have been violated, officials of AfAW tell HumAngle that obtaining justice for them has been challenging.

In Blessing’s case, for instance, they say they have had to remind the Police of their duty to charge Abeni in court. It also had to pay for things such as transportation fees (to government officials) and “other monies required by the clerks and state-appointed lawyer”.

Abeni, on the other hand, has not faced real consequences for his crime against 13-year-old Blessing and her father, having been able to meet the bail requirements.

Attempts by the organisation to bring him to book continue to be foiled by procedural challenges and the apparent ineptitudes of officials.

While the organisation has provided the prosecutor with financial and material support, he has, according to AfAW, “failed to handle the case with the expected sense of professionalism and commitment”.

“He failed to ask the judge to keep the suspect behind bars, given that he resisted arrest and tried mobilising his friends to the effect,” AfAW explained, going on to reveal other instances of ineptness, such as demanding money before accepting the case file from the Investigating Police Officer (IPO), attempting to convince Ijih and the family to drop the case, unexplained absence in court to argue the case as well as other issues that have delayed the case and prevented a proper hearing till date.

Currently, AfAW says it has employed the services of a new lawyer who has written to the commissioner of justice to have the case reassigned to his office so that he can take it over.

AfAW tells HumAngle that it is not their first rodeo, nor is it the only sort of challenge they face while fighting for those whose rights have been violated.

More often than not, the Police frustrate their efforts as well, he says.

“We get cases, swing into action, refer the case to the Police and they demand huge amounts of money from us before arresting those who are involved, and even when we pay in most instances, they still don’t do anything about it,” Ingye says, emphasising that this particular challenge is the reason AfAW, even though it has provided overwhelming evidence, has been unable to obtain justice for the victims whose cases they have handled.

Consequences are far-reaching

Apart from the physical torture that victims of witchcraft accusations go through, they additionally have to endure emotional and psychological trauma. Ijih, for instance, hurts every day because of what his little girl has had to endure. He wishes he could make it all go away.

“As an old man, I know myself, so I don’t bother to feel affected by whatever people are saying about me; I feel more concerned about Blessing,” he said. “I even told the principal that after some time, I will take her away from there [her current school].”

The damage wrought by the witchcraft accusation on Ijih and Blessing’s lives is such that the arrest and prosecution of the man responsible have done nothing to change how they are perceived by people.

“Nobody can meet me and my daughter today and say that we are witches, but they still see us with that eye until today,” he said.

For someone like 31-year-old Jude Abigi, whose mob trial was filmed, the consequences of a witchcraft accusation are as far-reaching as they can get. Not only was he sacked from his job, but he has become a recluse due to the stigmatisation that has trailed him since Oct. 28, 2023.

It happened around the time the genital theft hysteria peaked across different cities in Nigeria.

Abigi, a security guard with a bank (at the time), was going home at about 4:30 p.m. when he casually greeted a boy carrying two gallons of water, adding a few jokes as he would do with anybody.

About fifteen minutes later, when he saw the same boy coming towards him, stone in hand, Abigi thought nothing of it but would be utterly shocked when the boy suddenly charged at him and lunged the stone at his head, accusing him of stealing his genitals.

In a twinkle of an eye, he found himself ducking from more hands slapping, grabbing and hitting him. He landed in a gutter next, and when he was pulled out, it wasn’t for respite but for even more beating.

“Everybody was beating me. Some would park their motorcycles and begin hitting me,” Abigi said, remembering that they threatened to burn him as he repeatedly begged them to hear his side of the story.

The elderly people in the mob asked that he be allowed to explain himself, but all he said did not matter again when the boy, visibly furious, tore away his own clothes to prove to everyone the lies he believed Abigi was telling.

“He said that he has a very big manhood, but now his manhood is little,” he remembered the boy saying.

The boy may have been suffering from a condition known as Koro syndrome, and it had made him earnestly believe that Abigi, a stranger, had used witchcraft to steal his genitals when he greeted him.

Koro syndrome, first noted in northern China as far back as 7000 BC, is described in the first Chinese textbook of medicine as “an episode of sudden and intense anxiety that the penis (or in females, the vulva and nipples) will recede into the body and possibly cause death.” It was first documented in Nigeria in 1975 by a Kaduna-based Psychiatrist, Dr. Sunday Ilechukwu.

The syndrome has, however, manifested differently in both countries. While the Chinese sufferers, who see the issue as an imbalance of the yin and yang, panic over what they think is the receding of their organs, Nigerians tend to believe that theirs have disappeared by way of magic — hence Ilechukwu’s decision to name it “magical penis loss”.

The sufferers believed that when their genitals “vanished, they did not lodge inside the body but were supposed to have been magically taken by spiritually powerful persons or their agents for ritual purposes”.

Abigi was filmed while he was assaulted and humiliated. At a certain point, a knife and a gun materialised.

They searched his call log and realised that his pastor had been the last person he called. Having heard stories of a pastor who was killed and his church burned by people who believed he had connived with his members to steal penises for rituals, they became more convinced than ever that Abigi was guilty, so they made to end it once and for all by cutting off from him, what they believed he took from the boy.

Abigi, terrified at the knife edging closer to his genitals, told the crowd what they wanted to hear.

“I began telling lies so they would take me to my pastor,” he narrated, explaining that he added more details that would make them believe his pastor had indeed sent him to steal penises. He led them to the pastor. They beat the pastor up and bundled him into the trunk of a car.

On reaching yet another location, they made the decision to kill Abigi and his pastor.

“They put our legs inside a tyre and poured petrol from our head down,” he said, gesturing with his hands how the petrol was poured all over their bodies.

Just as the mob lit a match and threw it at them, the pastor’s wife arrived at the place with police officers in tow. At the police station, Abigi was treated, and the officers took his account of the events of that day.

Stigmatisation, loss, and reclusion

Even though he initially wanted to, Abigi was advised by his brothers against prosecuting his assaulters, as they did not have the financial means to follow it through. Deprived of the little respite that seeing his tormentors in jail might have given him, he had to quietly nurse his wounds.

He had barely registered the shock of all that happened to him when two days later, he was sacked from his job. “They [the management] had seen the video and said it is a disgrace to them,” he said.

While he grappled with the loss of his job, he also had to deal with the immense shame of having dehumanising videos of him out on social media, where strangers and those who know him could see them. He was further afraid of leaving his house.

Having lost his job, Abigi had to brave it and leave the confines of his house to a building site. He noted, to his dismay, that things had also changed there.

“Some people at my site believe what happened, and people are even afraid of me,” he said, stressing how adversely affected he had been by the incident. “If government work can come, I will be applying for them rather than to be hustling these ones because they cannot accept me in any site again.”

Once, he had tried entering a building site with hopes of securing a job as a mason but he had to withdraw when he saw people there pointing fingers at him. The stigma followed him everywhere like a stubborn stench.

“Anywhere I go, people would call me Mr Penis. I really felt very bad, but such is life.”

While he faced ridicule and rejection from all fronts, he also painfully bore the resentment of his pastor who, even though said he had forgiven him, had clearly not forgotten the near-death experience he suffered on his account. Abigi understood that his pastor was hurting as he was also filmed by the attackers, and so he continued to be cordial to the clergyman until he recently came around and completely forgave him.

Although the incident took place last October, the emotional and psychological impacts that the witchcraft accusation has had on Abigi remain with him. Currently, he stays home all the time, only ever stepping out in the evening when he strolls just around his vicinity and never beyond.

AfAW’s Ingye tells HumAngle that the stigmatisation and other sufferings Abigi is facing are not peculiar to him.

“It is a common pattern noticed in most of the cases handled by AfAW,” Ingye said, listing other victims who lost things and were forced to leave their homes as a result of witchcraft accusations and resulting attacks.

“In most cases, alleged persons are accused and banished from their communities; that is if they survive the attack.”

Tsav, the belief enabling accusations

One afternoon in a village in the Buruku Local Government Area, Tyawerse had just come back from dropping off some of his relatives and was squatting by his car examining his tyres when his son lounged at the car with a stick, hitting and breaking its windscreen, headlight, trafficator, and other things.

He was just about to directly attack him when people, drawn by the shouts of Tyawerse’s mother and wife, came to his rescue.

Earlier that day, while his father was away, Tyawerse’s son had told his grandmother that he was going to kill his father because he believed the man to be responsible for the miscarriage his wife suffered before, the stillborn child she birthed later, the death of their toddler, and for the sickness he was suffering from at that time.

Before the attack, though, Tyawerse had underlying issues with his son; for one, the young man (who was an offspring from his first marriage) grew up soaking up his late mother’s grievances against his father and thus never completely warmed up to him.

The main issue, Tyawerse says, however, arose when, after four years in the university, his son had no credible explanation as to why he had not been called up for the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC), a mandatory service for graduates of tertiary institutions in Nigeria.

“One day, I decided to go to the school, and I discovered that for four semesters, he didn’t pay his school fees,” Tyawerse said, explaining that he made sure to provide the fees for him. “He was writing exams all along, and although the results showed that he did not have carryovers, he was owing school fees and must clear it before he could go to service.”

He added that he was deeply disappointed and refused to provide the outstanding fees. This refusal would, in turn, cause a rift between them, which Tyawerse believes partly influenced the witchcraft accusation and assault. He also suspects that his son’s genuine belief in Tsav led him to the accusation and assault.

The Tsav belief system rests on confidence in the ability of individuals to harness and inflict harm with supernatural powers. Those who are suspected of being witches (possessing supernatural powers) are referred to as Mbatsav.

“It is commonly believed that witches use Tsav to inflict harm, manipulate events, and seek revenge on those who have wronged them,” Ingye explained.

Although the words Tsav and Mbatsav are Tiv words and the belief prevalent among the Tiv people of Benue State, it is not isolated or peculiar to them as other ethnic groups have similar beliefs. “Benue people, irrespective of ethnic affiliation, hold tightly to these beliefs and are likely to use them to explain happenings around them,” he emphasised.

A very difficult task

Before he established the Advocacy For Alleged Witches in January 2020, Dr Leo Igwe, who is also founder of the Nigeria Humanist Movement, had witnessed witchcraft accusations growing up and had later gone on to write his thesis on the dynamics of such accusations in Northern Ghana.

“The main objective of this initiative is to create a witch-hunting-free Africa by sensitising Africans on witch hunting and spearheading the advocacy for alleged witches within Africa,” Igwe stated on the group’s website.

Over the years, AfAW’s advocacy has come across numerous setbacks and difficulties, and just like in other states in Nigeria, the advocacy to protect the rights of accused persons has faced its fair share of challenges in Benue.

Apart from the challenges with the Police, the organisation also struggles with media coverage (of cases and their programmes) so much that the witch persecution in Benue has failed to attract needed attention like incidents in the South-South region of Nigeria.

“This [the notion that witchcraft accusation is not prevalent in Benue] is a wrong impression that I have been working to correct,” Igwe told HumAngle in a chat.

Ingye, the Benue State Director, says the media coverage is so poor that sometimes, the organisation only gets to hear about some cases years after they had taken place, and even then, it is through different links usually not related to the press. This problem, he explains, exists because there isn’t efficient independent media in the state.

“Whenever we invite journalists to come and tell these stories, they are just simply interested in what they are going to get from us; the passion to actually do the work is not there,” he said.

As in other states, they also face a funding problem as they have to cater to various needs of the cases as well as the victims, and this requires them to pay for things like transportation fees, hotel fees, and medical bills in the case of those who are injured, resettle some victims, and in some occasions provide for families whose breadwinners have been incapacitated as a result of witch accusation and persecution.

“We don’t receive funding from the Nigerian government or individuals in Africa because Africans are very suspicious people,” he said. They are instead funded by Humanists International, a non-governmental organisation based in the Netherlands.

The advocacy has also faced some opposition from the government of the state. Once, AfAW organised a seminar, only for it to be disrupted by police officers acting under the government’s directives.

“The Police claimed that they got some ‘intelligence’ that witches were meeting at the venue and were instructed to stop the meeting,” Igwe said, explaining that they were prevented from holding the seminar even after they explained their motive to the officers, who later admitted they were misinformed.

Even after the seminar was rescheduled for a later date, the organisers were invited by the Department of State Security (DSS) to “enlighten” them about the event. “This invitation was disturbing. The DSS works in secret, and an invitation meant that they must have uncovered something of real concern,” AfAW said.

Asked about the possibility of the state government being more supportive, Ingye couldn’t be clearer in his answer: the chances were zero.

For one, he believes that the person of the current governor, Rev. Fr. Hyacinth Alia, makes this rather inconceivable as, according to him, Alia had risen to fame in Benue precisely because of his belief in the existence of occultic powers and his many deliverance masses held to cast them out.

“I grew up knowing him [the current governor] as an exorcist priest: somebody who claims to drive out demons and witches, battle them and all that,” he said. People from faraway villages would attend his healing masses armed with jerrycans of water, which they brought to him to “bless and salt for them to go and fight witches and all that”.

A Google search on the governor seemed to prove Ingye’s statement.

“Hyacinth Alia, a reverend father, has always been a household name in Benue state. Famous for healing the sick and exorcising demons with a sprinkle of holy water, Alia’s name fast became a point of reference for testimonies,” the first paragraph of a close-up article on the governor read.

Ingye tells HumAngle that even though the premise of the governor’s reputation makes it unseemly for him to support AfAW’s advocacy, he would love more than anything to be proven wrong.

He believes that support, recognition, or even a non-hostile gesture from the government would go a long way in helping the fight against witchcraft accusations in the state because saving one victim after the other may not prevent those who accuse them from doing the same to even more people.

To address the superstitious beliefs still held by some in the state, Leo Igwe started a critical thinking campaign that seeks to train and challenge young people to independently think, question, and challenge beliefs rather than succumb to them.

In the meantime, however, Ingye thinks that the Advocacy for Alleged Witches has a long way to go in Benue.

However, the police in Benue tell HumAngle they are collaborating with non-governmental organisations in the state to curb future occurrences of mob violence over witchcraft accusations. Anene Sewuese, the state’s police spokesman, told HumAngle that most victims of such accusations do not get a chance to report the case on time.

“If at all there are delays in getting justice, it won’t be from the police. We make arrests once such cases get to us and ensure arraignments,” he said.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter