What Resettlement Looks Like When The Gunshots Haven’t Stopped

After years in a displacement camp, Fati, like thousands of others, is being resettled into the town she once fled in Borno State, northeastern Nigeria. She worries about security threats, poor living conditions, and being separated from her loved ones.

There is a tenderness between Fati Bukar and her eldest son, Lawal.

When he sits next to her, she holds his hands. As he gets up to leave the room, she asks where he’s going, and he says he’ll be back soon. When Lawal returns and sits across from her, she taps the mat beside her, and he moves closer. She holds his hands again. He says something, and she laughs.

The next day, Fati and seven of her children are set to leave the Muna Garage camp for Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) in Maiduguri, the Borno State capital in northeastern Nigeria. They are heading to Dikwa Local Government Area (LGA), as part of a government resettlement programme to close the IDP camps in the state. The initiative began in 2021.

Lawal, however, will not be going with his mother and siblings.

His resettlement papers indicate that he will be taken to Mafa LGA, approximately an hour and a half from Dikwa. Both mother and son are deeply unsettled by this development.

Lawal had told the officials he wanted to be with his mother and siblings, but the arrangements didn’t go as he hoped. Since Lawal has a family of his own, he registered as a separate household from his mother, who was listed as the head of the household with his younger siblings. They assumed they would all be sent to Dikwa, their place of origin, but the resettlement programme does not always work that way.

With one arm paralysed from a motorbike accident, the 23-year-old can no longer farm efficiently. Instead, he guides his younger siblings through it, showing them what to plant, how to weed, and when to harvest.

Fati is especially close to Lawal, and the thought of their separation weighs heavily on both of them.

She and her children have lived in the Muna Garage IDP Camp for seven years.

Fleeing home

Back in 2014, as news of insurgency spread like wildfire, and terrorists invaded town after town in Borno, Fati and her husband hadn’t decided to leave their village in Dikwa yet. They were holding on to hope that maybe the war would end. Still, she thought the worst-case scenario would be displacement.

She was wrong.

The worst-case scenario unfolded as she was tending to her livestock by a stream when someone came running to tell her that her husband had been shot.

She let the animals loose and ran home, crying, in disbelief, her heart pounding as she inched closer to her husband’s lifeless body.

“I fell, and for the next three days, I didn’t even know what was going on. It was like I was going in and out of consciousness,” Fati narrated, her hands lifted, then fell, as if even they had lost the will to explain.

Grief consumed her completely, but survival demanded she keep going. So in 2018, she gathered her eight children and headed into the bush, trying to find a way to Maiduguri.

They eventually found safety at the Muna Garage IDP Camp, a crowded settlement on the outskirts of the city full of families like hers; people who had lost homes and loved ones to the Boko Haram insurgency. The camp shelters about 10,000 displaced people.

Fati shared her story with HumAngle through an interpreter, who bridged the language barrier. It was a scorching Sunday afternoon in the camp, and people were packing and preparing for the journey ahead.

“I don’t want to go,” Fati frowned. “I know the kind of terror that made me come here. I know how much we suffered. Why would I go back to such danger?”

There is anger in the pitch of her voice and the sharp, insistent gestures of her arms.

After the conversation, she agreed to show what packing looked like.

Fati ducks to enter her thatched room, which has a small partition just inside the entrance, so that her makeshift bed isn’t immediately visible to anyone stepping in. The air inside is warm and still.

“I don’t have a lot of things, so they’re just in this bag,” she says, pointing to a bag and two sacks beside her bed.

“The first time we tried to flee from our homes before coming here, soldiers chased us back. So we had to try again. When I left, I knew I wouldn’t go back until everywhere became safe. But is it even safe now?” Fati reflects.

The return

It’s been four years since the Borno State government began working to close all official IDP camps in Maiduguri and resettle displaced people, either back to their home communities or new locations across the state.

Governor Babagana Zulum maintained that “we will never eradicate insurgency without resettling people,” arguing that the camps have become sites of deepening social problems, including child abuse and prostitution.

The United Nations defines resettlement as a “voluntary, safe and regulated transfer of people [and] is intended as a long-term solution.”

But that’s the theory. In reality, many residents in the Muna Garage Camp remain hesitant. They are unsure what they are returning to or what kind of life awaits them.

Some are returning to places where security remains fragile. Others are being moved to unfamiliar towns with no jobs and no clear path forward. What was meant to be a temporary displacement now stretches into a second chapter that looks different but feels just as unstable.

With resettlement comes many fears: the fear of starting all over again, the fear of the unknown, and most terrifying of all, as Fati puts it, the fear of “coming face to face with the terrorists you fled from almost a decade ago.”

“If I go back there, what I fear most is that I won’t have peace of mind. That I’ll be constantly thinking, ‘Will the terrorists come today? Will they come tomorrow?’ That alone is enough to make someone lose weight, to live in constant fear. That alone is enough.” Fati says, then looks down at the floor, and starts to draw invisible circles with her index finger.

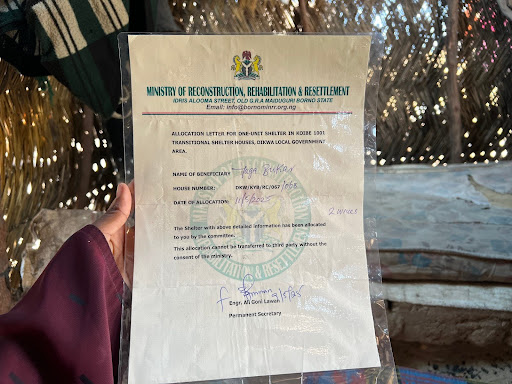

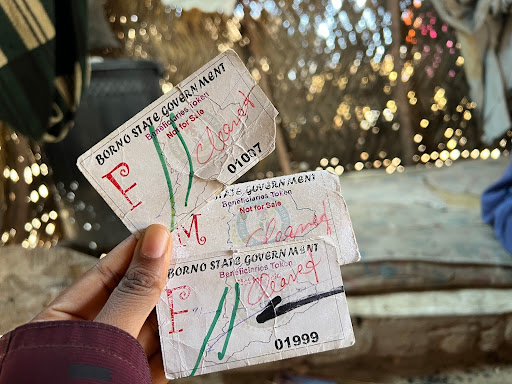

Outside the hut, a cluster of people sat together in the open, under the shade of trees, waiting to collect documents needed to claim shelters in Dikwa. They were also given meal tickets, with both the papers and tickets handed to heads of households.

The buses arrived at sunrise on Monday, May 12.

Even before they left, parts of Muna Camp were already coming down. Huts made of straw and tarpaulin were dismantled. A crowd formed near the camp’s edge where HumAngle met Fati amidst the chatter of people, children playing, and some murmuring their unwillingness to leave.

She was squatting, shielding her face from the sun with her hands. When asked whether she is tired, she simply smiles. She was very quiet but managed to say, “I’ve packed up. We’re just waiting to leave now.”

Then she continues looking into the distance.

They left around 11 a.m.. Lawal stayed behind and waved goodbye to his mother. A few hours later, he tried to call his brother, but the call didn’t go through. It turns out that his brother’s mobile network, like many others’, doesn’t work in Dikwa. His mother’s phone was also switched off. It wasn’t until later in the day that he could finally reach them. They told him they had arrived safely.

Still not safe

Soon after their journey to Dikwa, Fati’s fears started to materialise.

Although HumAngle couldn’t reach her for a few days after their trip, we were able to reach other returnees.

“We keep hearing gunshots at night. People are going back to Maiduguri in scores. Everyone is scared,” one of them, Kaka, explains over the phone.

The following day, on Friday, May 16, Kaka reached out to HumAngle and said, “I just called to tell you I am back to Maiduguri. I can’t live there with my baby. But my parents are still there.”

Kaka is now staying with a neighbour in Muna camp who, like Lawal, was meant to be relocated to Mafa. However, none of those assigned to Mafa have been relocated yet, so a few rooms in the camp remain standing. She had heard about an ISWAP attack in Marte, a nearby town, which forced thousands of people to flee to Dikwa.

That attack is one of several recent signs of ISWAP’s resurgence in Borno State, including another in Dikwa on May 13. These incidents have prompted many to flee again, with some heading towards the Cameroonian border and others to Maiduguri.

Some security analysts and international groups say the resettlements are ill-timed. They point to recent attacks and the ongoing threat from ISWAP as signs that many areas remain volatile. The violence, they argue, reflects a level of instability that makes voluntary return difficult, if not dangerous. Without consistent safety, people are unlikely to settle and may continue to move.

For example, the International Crisis Group has warned that these resettlement efforts are “endangering displaced people’s lives,” especially in areas that “tend to lack rudimentary health care, education and other state services.”

With no updates from officials and the relocation to Mafa still on hold, Lawal decided to travel to Dikwa on Sunday, May 18, to check on his mother and siblings.

Fati was delighted to see him.

“When she saw me, her face lit up with a smile,” he said. “She looked over my shoulder and asked, ‘Where is your wife? Why didn’t you come with her? I kept a room for you that used to belong to a woman who has returned to Maiduguri.’”

Fati wants him to stay, because “it’s easier for the family.”

She tells HumAngle that they are fine and prays no harm comes to them.

“When we arrived, the government gave us one bag of rice, four litres of cooking oil, seasoning, a few measures of guinea corn and ₦50,000,” Fati says. “The problem is that there’s no running water even though they [the officials] said they’ll sort it out. The toilets are quite crowded too because some of them were damaged by the wind, so there aren’t enough.”

Fati explains that, while they are getting by now, the future remains uncertain, as there will be no food once their current supply runs out. The farmland in Dikwa is far, and going there means risking an encounter with terrorists. Reaching the fields also requires a bicycle or motorbike, neither of which they own.

These poor living conditions and persistent threats have forced many returnees in other communities to flee once again, despite having been resettled in recent years through the same programme. Kaka’s return to Maiduguri, for instance, is not an isolated case; several families have also left Dikwa.

Such recurring setbacks paint a bleak picture for Fati and her family.

For now, she is focused on surviving each day in Dikwa, caring for her children, rationing food, and holding onto hope. What she wants most, she says, is not just food or water, but peace.

When HumAngle last spoke to her, over a week after the trip to Dikwa, Fati still sounded worried, but there was also a lightness.

In the background, Lawal teased her attempts to greet in Hausa, a language she doesn’t speak. She laughed. Then he took over and facilitated the conversation, fluently translating her Gamargu to Hausa and vice versa. But laughter needs no translation, and neither does the anxiety in Fati’s voice.

Fati Bukar and her children are being resettled from the Muna Garage IDP Camp in Maiduguri to their original home in Dikwa, Borno State, as part of a government initiative.

Despite the hope for a new start, the separation from her eldest son Lawal, who is being relocated to a different area, intensifies her reluctance to leave. Fati recalls the trauma of losing her husband to insurgency violence, which forced her to flee with her children to the camp in 2014.

Upon arrival in Dikwa, Fati is faced with an unstable situation, with reports of nearby insurgent activities causing fear among returnees. The resettlement program's limitations, such as inadequate resources and continued security threats, challenge the program's promises of safety and stability. Some families, including Kaka’s, have already fled back to Maiduguri due to these issues. While Fati strives to care for her family with limited provisions, her primary wish is for peace and stability in their lives.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter