What JNIM’s Entry into Nigeria Means for Security in the Sahel

Though limited in scale, JNIM's entry into Nigeria signals a potentially dangerous expansion that could redraw the map of insecurity across West Africa.

On the morning of Oct. 31, a short propaganda message began circulating across jihadist-aligned online channels. Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), the al-Qaeda-linked coalition that has spent the past decade reshaping conflict dynamics in the central Sahel, claimed responsibility for an attack inside Nigeria.

The claim, which was later accompanied by a video, revealed that the group killed a soldier at a border community in Kwara State, North Central Nigeria. The video showed the aftermath of the attack.

That incident is JNIM’s first publicly acknowledged violent operation on Nigerian soil. Earlier, in July, the terrorist group released a video claiming it had established a foothold somewhere in Niger State, also in the North Central region, where Ansaru, another al-Qaeda-linked group, dominates.

The October incident might seem small, yet the implications are not.

For years, JNIM has been the most resilient jihadist force in the Sahel, steadily expanding its reach across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Its presence, especially along the region’s porous borders, has challenged state authority, displaced millions, and contributed to one of the world’s fastest-growing humanitarian crises.

Nigeria, already battling multiple terrorist groups such as the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JAS), Lakurawa, IPOB, and other armed groups, has so far remained outside JNIM’s core theatre.

This, however, may now be changing.

A symbolic crossing

There is no evidence yet that JNIM has established permanent bases within Nigeria. The reported attack appears closer to a reconnaissance operation than a territorial campaign.

Even so, history suggests such incursions rarely occur by accident.

In Mali and Burkina Faso, JNIM’s expansion followed a familiar pattern. Small, initially ambiguous attacks were used to test military responses, identify sympathetic local actors, and map security gaps. Over time, these probing operations gave way to deeper entrenchment, including the imposition of parallel governance systems, taxation, and courts.

For instance, just a few months after it was formed, JNIM, through its Katiba Macina wing, ambushed the Malian forces near Dogofry on May 2, 2017, killing nine soldiers and injuring five others. This marked JNIM’s first attack in western Mali and was followed by many others once the group had tested the military’s readiness to respond and counterattack.

Seen in that context, the October attack may represent a strategic signal rather than an isolated act of violence. The group might be testing a loophole in Nigeria’s security architecture that could allow it to create additional fronts in Nigeria’s central region.

JNIM rarely announces a presence unless it believes the ground is already prepared.

Local networks

JNIM’s growth across the Sahel has not depended solely on the movement of fighters across borders. Rather, it has thrived by embedding itself within existing local conflicts.

A similar model may now be unfolding in northwestern Nigeria.

Over the past five years, the region has witnessed the rise of several terrorist groups. Among them is Lakurawa, a violent network operating across parts of Sokoto, Kebbi, Zamfara, and Katsina states. Initially framed by some officials as “harmless herders”, Lakurawa was designated a terrorist group by Nigerian authorities in September 2024 following a series of attacks, forced displacements, and the imposition of social control over rural communities.

Security analysts warn that such groups provide fertile entry points for transnational jihadist movements. “JNIM can sow chaos by tapping into armed group networks,” said Taiwo Hassan Adebayo, a Lake Chad Basin researcher at the Institute for Security Studies.

As seen elsewhere in the Sahel, JNIM has demonstrated its ability to forge tactical alliances with non-ideological armed actors. In exchange for training, weapons, and access to transnational funding networks, local groups offer intelligence, mobility, and legitimacy within their communities.

This convergence often blurs the distinctions between crime and insurgency, making the violence harder to contain and even harder to resolve.

Another key variable in JNIM’s potential Nigerian expansion is Ansaru.

Once a faction within Boko Haram, Ansaru formally broke away in 2012, aligning itself ideologically with al-Qaeda rather than the Islamic State. Though weakened by arrests and internal fragmentation, the group has never fully disappeared. In recent years, Nigerian and international security assessments have noted signs of renewed activity, particularly in the North West and North Central regions.

Ansaru’s ideological alignment makes it a natural bridge for JNIM. A 2020 report by the International Crisis Group confirmed an informal connection between Ansaru and JNIM, under which Ansaru members received training and weapons from JNIM due to a shared al-Qaeda affiliation.

“Ansaru, which has a long history of operating in the North West, where it engaged in the high-profile kidnapping of expatriate engineers between 2012 and 2013, is forging new relationships with other smaller radical groups in Zamfara State, particularly in the areas around Munhaye, Tsafe, Zurmi, Shinkafi, and Kaura Namoda,” the report noted.

Taken together, this indicates that JNIM offers Ansaru a functioning regional command structure, battlefield experience, and access to transnational jihadist networks. Ansaru, in turn, provides local knowledge, historical roots inside Nigeria, and pathways to recruit local armed groups into JNIM’s orbit.

Whether this relationship remains informal or evolves into something more structured will significantly shape the threat landscape.

Should JNIM formalise ties with terror groups in Nigeria, the country risks becoming part of a wider Sahelian war.

Civilian risks

Wherever JNIM has established a foothold, civilians have paid the price.

Across the central Sahel, more than four million people have been displaced, over 8,000 schools have closed, and at least 12 million people face acute food insecurity.

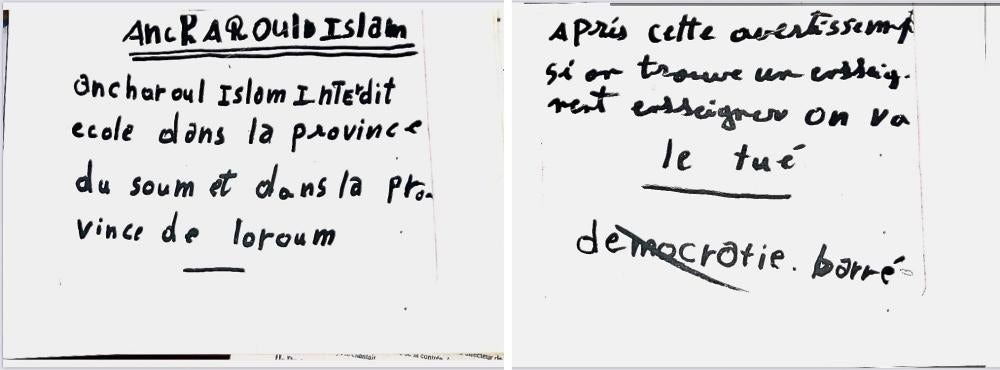

In Mali and Burkina Faso, resistance to jihadist rule has led to the wholesale abandonment of communities and markets. Recent JNIM fuel blockades have further paralysed the region, forcing the temporary closure of Malian educational institutions.

Meanwhile, the combined pressure of systemic insecurity and military juntas governing host countries has forced humanitarian agencies to suspend the very operations these populations depend on.

Since the fuel blockade in Mali began in September, JNIM has ambushed fuel tanker convoys on key routes, burning trucks, kidnapping or killing drivers, and looting fuel. This has led to hardship and economic sabotage in Mali, especially in Bamako.

By comparison, Northern Nigeria’s dependence on fuel trucks from the southern region creates a critical economic vulnerability. Ansaru, operating from its bases in the country’s North Central, could replicate JNIM’s strategy in Mali by attacking strategic supply routes to cripple the economy and undermine the state.

Nigeria’s northern region already faces severe humanitarian strain. The introduction of a Sahelian jihadist actor could further restrict access for aid groups and deepen food insecurity in already vulnerable areas.

For civilians, the distinction between terrorists in the North West and ideological insurgents like ISWAP and Boko Haram offers little comfort. What matters is whether they can farm, trade, and live without fear.

A limited, dangerous window

Nigeria still has an opportunity to prevent JNIM’s entrenchment.

“Unlike parts of Mali and Burkina Faso, where state authority has collapsed across vast rural areas, Nigeria retains functional institutions, an experienced military, and a relatively robust civil society,” Bello Mammadou, a Nigerien postdoctoral researcher on the extremist insurgencies in the Sahel, told HumAngle.

However, the window for action is narrow, he explained.

Heavy-handed military campaigns risk alienating communities and fuelling recruitment. Neglect, on the other hand, creates space for terrorists to present themselves as alternative authorities.

According to Mammadou, lessons from the Sahel suggest that responses must combine targeted security operations with local governance reforms, community engagement, and efforts to dismantle the financial networks that sustain armed groups.

“Anything less than that can only temporarily stop the terrorist operations, not entirely dismantle them,” he said.

Regional stakes

JNIM’s potential expansion into Nigeria is not merely a Nigerian security challenge; it represents a serious regional threat with far-reaching implications for West Africa.

Conflicts in the Sahel have consistently shown that insecurity does not respect national borders, as demonstrated by the tri-border axis of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. JNIM has repeatedly exploited these gaps, adapting more quickly than state institutions.

Terrorist groups thrive where regional coordination is weak, where political instability persists, and where fractured alliances prevent unified responses. In this context, the growing diplomatic rift between the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) risks deepening regional instability.

Following a series of coups, the military juntas of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger withdrew from ECOWAS to form the AES. This exit marked a formal fallout with Nigeria, Benin, and other West African nations, triggering the collapse of regional counterterrorism cooperation, particularly in the Lake Chad region.

The breakdown in cooperation, coupled with mutual distrust and competing security frameworks, undermines intelligence sharing, joint military operations, and coordinated border control. This fragmentation creates openings for groups like JNIM to expand, reposition, and exploit ungoverned spaces.

Should Nigeria become integrated into JNIM’s operational theatre, the repercussions would extend across West Africa, further straining already fragile security architectures.

“Without renewed political dialogue and security collaboration between AES and ECOWAS members, counterterrorism efforts will remain disjointed, increasing the likelihood that terrorist activities spread and intensify across the region,” Mammadou added.

Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), an al-Qaeda-affiliated group operational in the Sahel, claimed responsibility for its first attack in Nigeria, specifically in Kwara State. This marks a critical point as JNIM has expanded its influence beyond its usual territories of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, already burdened with humanitarian crises. The group's expansion historically involves tactical intrusions to identify security gaps and local allies, potentially setting a similar precedent in Nigeria.

The potential infiltration into Nigeria poses significant regional challenges, given the country's ongoing battles with other terrorist entities like ISIS' West Africa Province. JNIM may capitalize on local conflicts and networks, muddling crime and insurgency lines, and leveraging associations with groups like Ansaru for bolstering their influence in Nigeria. There's a narrow window for Nigerian authorities to prevent JNIM's entrenchment, which requires a strategic mix of military and governance tactics to forestall the group's integration into Nigeria's security landscape.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter