What A Normalised Israeli-Sudanese Relation Means For Security In The Sahel

Shortly after overseeing a successful diplomatic deal between Israel and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the United States (U.S.) has started pushing for the establishment of similar ties between the Middle East country and Sudan. And this may have far-reaching consequences for security in the Sahel region.

Known as the Abraham Deal, the bilateral agreement with UAE was announced on Thursday, August 13, by U.S.

President Donald Trump. It cements relations pertaining to commerce, tourism, direct flight operations, scientific cooperation, security and, eventually, full ambassadorial ties.

In return, the UAE had asked Israel to stop plans to annex parts of the West Bank, a landlocked territory widely considered to be illegally occupied Palestinian land. For Israel, the agreement is a welcome step in ultimately ending its isolation in the Middle East and improving its reputation globally.

Fired up by the breakthrough, the U.S. is now prepping for the normalisation of Israeli-Sudanese relations.

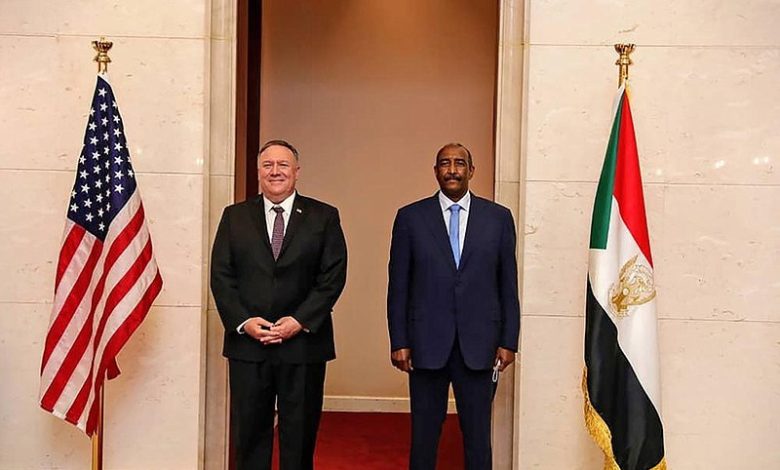

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in a recent visit to the African country discussed the possibility of removing it from the list of state sponsors of terrorism to which it was added in 1993 as well as “continued deepening of the Israel-Sudan bilateral relationship”.

The Sudanese transitional government, which took over after a coup that deposed former President Omar al-Bashir last year, has, however, replied that it lacks the mandate to make such resolutions.

All the same, if the country decides to formalise diplomatic ties with Israel, this might have significant consequences on its political stability and the direction of terrorist activities in the region.

Sudan’s keg of gunpowder

Sudan has a notorious history of serving as a transit hub and haven for jihadi terrorists because of its size and strategic location. It is the third largest country on the continent and is bordered by Egypt, Libya, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, South Sudan, Central African Republic and the Red Sea.

When it was designated as a state sponsor of terrorism, it was based on the allegation that it supported international terrorist groups such as the Abu Nidal Organisation, Palestine Islamic Jihad, Hamas, and Hizballah.

The government has since joined hands with the U.S. in counterterrorism and deradicalisation initiatives. But the battle is far from over.

“Despite the absence of high profile terrorist attacks, ISIS [Islamic State of Iraq and Syria] facilitation networks appear to be active within Sudan,” the U.S. noted in its 2019 Country Reports on Terrorism.

“The newly appointed Minister of Religious Affairs and Endowments under the CLTG denied the existence of an official ISIS entity in Sudan but acknowledged that there were ‘extremists’ linked to ISIS in the country”.

Last November, the transitional government announced preparations to return between 16 and 20 terrorists from various groups to their countries of origin, including Egypt, Tunisia, Chad, and Nigeria.

Since the 20th century, radical young terrorists in Africa have considered a career in the Middle East to be the ultimate source of pride. This is because “it was considered far more dignifying to kill or be killed by a Westerner than to kill or be killed by local security forces”.

Those who could not make it to Afghanistan and other parts of the Middle East settled for the outskirts of places like Sudan, Algeria, and Libya, which served both as training grounds and transit zones.

In the 1990s, Sudan provided a haven for Osama bin Laden, the late founder of Al-Qaeda, who invested heavily in infrastructure in the country, including funding the construction of an airport at Port Sudan and a road connecting it to Khartoum.

Apart from receiving huge tracts of land for agriculture, the Al-Qaeda leader was able to build “several training camps in Sudan at which militants from Hamas, ANO, Lebanese Hizbullah and Algeria’s Armed Islamic Group (GIA) trained for terrorist operations”.

What is more, Sudan currently lacks the technical and physical capacities to make its borders less porous. “Sudan’s expansive size, and the government’s outdated technology and limited visa restrictions, present challenges for border security,” the U.S. stated in its Reports on Terrorism.

Anti-Semitism: a jihadi common ground

Even though the terrorists currently in Sudan hardly conduct attacks locally, this could change with the normalisation of relations with Israel because of strong anti-Semitic sentiments. And it could worsen if the deal involves the local deployment of Israeli or American military forces to boost counter-terrorism efforts and gather intelligence as foreign military presence has been found to be a “factor for recruitment into jihadist groups”.

Anti-Semitism has, in fact, been described as a “pillar of Islamic extremist ideology”. In a video message shared by Hamza bin Laden, Osama bin Laden’s son, in 2015, urged Muslims to support their brethren in Palestine by fighting the Jews and Americans “not in America and occupied Palestine and Afghanistan alone, but all over the world”.

Inciting anti-Semitic violence has been at the core of Al-Qaeda’ ideology and is also a popular propaganda message from the leadership of ISIS, Al-Shabaab, Boko Haram, among other groups, to motivate members.

According to the Anti-Defamation League, they “continue to rely on depictions of a Jewish enemy – often combined with violent opposition to the State of Israel – to recruit followers, motivate adherents and draw attention to their cause.

“Anti-Israel sentiment is not the same as anti-Semitism. However, terrorist groups often link the two, exploiting hatred of Israel to further encourage attacks against Jews worldwide and as an additional means of diverting attention to their cause,” the organisation stated.

Israel’s uncompromising position to halt further incursions into Palestinian territories and the grave human rights violations against Palestinians despite global condemnation have not helped the predominant Jewish nation.

Considering the silent presence of terrorists from various backgrounds in Sudan and the anti-Semitic agenda that unifies them, normalisation of ties with Israel by the government might backfire, especially as the state still lacks adequate means of clamping down on jihadi groups.

Meanwhile, strong views against the Israeli government are not only common among extremist groups. The transitional government is also palpably divided on the issue and what shape the country’s foreign policy should take.

“Israel must actively seek friendship and a real relationship with all stakeholders in Sudan to guarantee that the Sudanese populace will not reject such a relationship in the future,” Areig Elhag, an expert contributor at The Washington Institute, suggested.

Elhag added that national dialogue and a popular referendum should be held on the subject.

“Ignoring the civilian side of relations will not be in Israel’s future interests,” he said.

Elhag pointed out that this was important “especially as the Forces of Freedom and Change and the Assembly of Professionals, the primary incubator for Prime Minister Hamdok, have a large influence on the Sudanese populace.”

A double whammy?

Sudan is desperate for economic support with a quarter of its population estimated to be in need of humanitarian support as well as an external debt of 60 billion dollars, nearly 200 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product. But it is unlikely that what the country stands to gain from a formal deal with Israel is anywhere close to the costs.

The U.S. has already committed to lifting trade embargo against Sudan since 2017, in recognition of its “sustained progress” fighting terrorism and allowing humanitarian aid into Darfur. The sanctions, the United Nations said, had sustained a “cycle of poverty and desperation”.

It is not the first time the U.S. will be using removal from the terrorism sponsors’ list as a bait to get what it wants.

In 2010, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said the country would hasten to delist Sudan if it held a referendum to see if the southern region wanted to secede and adhered to the results. The government complied, ending a decades-long civil war, but the country remains on the infamous list.

The true condition for its removal appears to be the payment of a 300 million dollars compensation for victims of bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. Once this is done, legislation has to be passed by the American Congress and approval by the president before Sudan’s name can be finally taken off.

Besides, a look at the experiences of Arab countries that have normalised relations with Israel is not reassuring.

Following secret negotiations, Egypt was the first to sign a peace deal with the country in 1979, then Jordan in 1994. While Egypt regained possession of the Sinai Peninsula, for Jordan the motivation was potential economic incentives.

“Despite the treaties on paper, Egyptian and Jordanian relations with Israel have hit some lows over the years. The countries often maintain close security cooperation, and Israelis frequently vacation in Egypt’s Sinai. But the economic benefits promised have often not materialised,” summarised Miriam Berger, a staff writer at The Washington Post.

Though Egypt was suspended by the Arab League between 1979 and 1989 for entering into a treaty with Israel, no action was taken against Jordan. Public sentiments are, however, still strongly tilted against the Israeli state across the region.

Seeing the Abraham Acc as a betrayal and “blow to the Arab Peace Initiative”, the Palestinian Authority swiftly withdrew its ambassador from the UAE in protest. Iran and Qatar have also condemned the accord, and Turkey similarly threatened to recall its ambassador from Abu Dhabi.

Although suspending the West Bank annexation move seemed to have sealed the deal, Israel has insisted it has only agreed to a “temporary postponement”.

“Ultimately, the deal is only as strong as the benefits all parties get, and yet again with Trump in office, Netanyahu appears to have bagged the lion share of those,” argued CNN international diplomatic editor, Nic Robertson.

It would, therefore, be wise for the Sudanese transitional government to carefully consider the pros and cons to avoid escalating conflict both locally and in the Sahel region that could undo the progress made since Al-Bashir’s administration was toppled.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter