Weaponised Identity: From Dreadlocks to Dialects, How Profiling Threatens Lives in Nigeria

Nigeria’s obsession with stereotypes deepens division, fuels mob violence and exclusion, erodes due process, and obscures the real drivers of conflict. Breaking this circle requires a shift towards truth, equity, and nuanced engagement.

“I wear a niqab and a full jilbab. People often tell me that I am oppressed,” says Hajja Gana, a Nigerian housewife and mother of four.

“Once, when I was walking through a market in Kano, I heard traders yelling and warning others: hatara. I later learned that some women who wear hijabs steal and hide things in their clothes.”

When the Hausa word “hatara,” which means “be aware” or “be careful”, echoed through the market, people turned to look at her. They were suspicious, hostile. She hadn’t done anything wrong, but in that moment, her hijab felt less like a sign of faith and more like a verdict on her character. “This happened in Kano, not in France or elsewhere, where there is a ban on hijab,” she said.

The mother of four felt ashamed and out of place. For the first time, she wondered if her hijab, which she was proud of and thought of as part of her identity, was now a problem that made people look at her and be afraid. That day, a seed of doubt was planted, which may take years for her to shed.

In Nigeria, profiling doesn’t wait for context. A woman in a hijab can feel the sting of stigma among her own, and families cast away school dropouts, leaving them vulnerable to drugs or desperation.

A carpenter recounted to HumAngle how soldiers once cut off his dreadlocks at a checkpoint in Gora, along the Abuja-Keffi road, because he dared to answer a phone call in their presence. “I am still scared to grow my dreads back,” he said, two years after the traumatic incident.

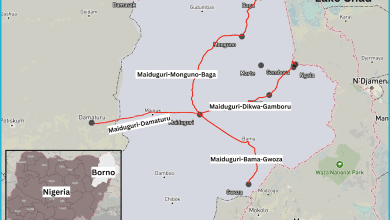

Profiling in Nigeria manifests in whispers, weapons, mob chants, and silent judgments. People from Borno State in the northeastern region, for instance, were routinely harassed at checkpoints during the height of the Boko Haram crisis simply for having a Maiduguri vehicle plate. “It was hard to be Kanuri,” reminisced Arch Shettima Abba, a resident of Borno State, emphasising that his identity as a Kanuri man became grounds for suspicion, as many Boko Haram members who are fighting to overthrow the government and establish an Islamic state are Kanuri-speaking.

“I met a girl in Dei-Dei, Abuja,” shared Muhammad Modu Lamba, 33, a business owner. “She said my accent was strange. When I told her I’m Kanuri from Maiduguri, she said I must be Boko Haram and told me to leave before I commit a suicide attack.”

A conflict reporter and media executive has faced years of profiling, harassment, and exile for his groundbreaking coverage of Boko Haram in Lake Chad. Despite surviving multiple assassination attempts and dozens of arrests, he has never been charged. His relentless reporting elicited deep suspicion from colleagues and intense scrutiny from authorities.

“The stigma of being associated with terrorism,” he claims, “is worse than the stigma of living with HIV in the 1980s and 1990s.” This experience serves as a stark reminder of the dangers that journalists face simply for reporting the truth in some of the world’s most dangerous areas. “I still can’t get over the trauma from years of stigmatisation. The stigma is worse than the threats and violence levelled at me.”

This weaponisation of identity cuts across every strata of society—from language to attire to religion, and often leads to persecution.

The risk of being Fulani

When Governor Charles Soludo of Anambra State recently denied that “Fulani herders” were responsible for killings in the South East, his statement punctured a dangerously widespread narrative. “Those who did the killings are criminals, not Fulani herdsmen,” he said. “We need to be careful not to make things worse by making false accusations.”

Soludo’s comments were a warning. In Nigeria’s public discourse, particularly online and in mainstream media, “Fulani” has become shorthand for danger. This framing dominates the South South, South West, and North Central regions. In 2023, Anka residents in Zamfara State, North West, blocked a major highway in protest over insecurity. In retaliation for what they described as ‘Fulani criminal violence’, they also set fire to displacement camps with a Fulani majority as part of the protest.

“We host and accommodate the innocent Fulanis in Anka town, but their relatives did not stop killing and kidnapping us,” one protester told HumAngle.

Such stereotyping distorts the truth by obscuring evidence, inflaming tensions, encouraging retaliation, and undermining Nigeria’s already fragile social fabric.

One story, many consequences

In 2016, the town of Nimbo in Enugu State was rocked by an attack that claimed many lives. Politicians, media outlets, and activists quickly blamed “Fulani terrorists.” Later investigations revealed that criminals from various communities were involved, yet the Fulani label stuck.

That same year, more than 300 people were killed in Agatu, Benue State. Again, Fulani herders were blamed. Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, the tragedy was woven into a growing national narrative of Fulani culpability, erasing the existence, let alone the slightest chance, of the involvement of local militias.

By 2021, the Fulani identity had become nearly synonymous with criminality, amplified by mass kidnappings and terror activities in the Northwest across states like Zamfara, Kaduna, and Katsina. Even in incidents with diverse perpetrators, Fulani herders faced the brunt of suspicion and hatred.

After the St. Francis Catholic Church massacre in Owo, Ondo State, in July 2022, authorities initially suspected the terror group Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), but within hours, the public blamed Fulani herders. It was later found that a violent criminal network linked to cultism may be behind the attack, but by then, distrust and fear had already taken root.

Ethnic fear as political currency

Insecurity in Nigeria is multifaceted, with insurgency in the North East, separatism in the South East, and multi-layered acts of terrorism in the North West. Yet, Fulani communities are increasingly scapegoated for this widespread violence.

Some leaders have exploited these fears. In 2019, a Southwest governor ordered Fulani herders to vacate forest reserves unless registered. Despite its framing as a security measure, many viewed the order as discriminatory and unconstitutional. Herder groups protested, while local communities hailed the move.

Weaponising ethnicity for political gain isn’t new; Northerners were labelled enemies during the June 12 protests. Kanuris were branded terrorists post-2009. During ‘End SARS’, ethnic narratives diluted the movement’s unity and focus. Across Northern Nigeria, derogatory terms are unfortunately used by many to describe non-Muslims and people from different ethnic or regional backgrounds. These expressions, often rooted in historical prejudice or ignorance, serve to alienate, stereotype, and dehumanise others.

Nevertheless, it is important to recognise that such divisive language is not confined to one region or group. Across Nigeria—in every region and among every ethnicity—there are slurs and expressions that reinforce harmful divisions. These words, no matter where they are used or whom they target, have no place in any society that seeks justice, inclusion, and progress.

The media and its double standards

The media plays a crucial role in either reinforcing or breaking stereotypes. Unfortunately, many outlets have leaned into ethnic scapegoating. Headlines such as “Fulani herdsmen kill 20 in Plateau” are common, even when there’s no confirmation.

Yet, when cult groups or armed militias from other regions act violently, ethnicity is seldom mentioned. In the Niger Delta, attackers are often called “militants” or “criminals.” The ethnic identity is downplayed or entirely omitted, creating a narrative that isolates violence as a cultural trait of some groups while absolving others of collective association. This double standard deepens bias, fans ethnic tensions, and undermines journalistic integrity.

When assassinations and kidnappings occur in the Southeast, perpetrators are typically described in vague terms such as “gunmen,” “criminal syndicates,” or “unknown gunmen.” Rarely is the ethnic identity of the attackers highlighted, even when there are strong indications of local involvement. Compare this to how the media handles similar crimes in the Northwest, where headlines quickly frame the perpetrators as “Fulani bandits,” “Fulani herders,” or simply “herders,” reinforcing a reductive ethnic profiling that feeds animosity and stigmatisation.

The media’s role in this linguistic sleight-of-hand is both consequential and dangerous. By selectively applying ethnic identifiers, the media fails its ethical obligation to report without prejudice. Such patterns distort truth and deepen divisions.

Real costs, real lives

The families of the 16 travellers lynched in March 2025 at Uromi in Edo State exemplify how negative profiling can be fatal. Some of the bereaved family members shared harrowing details with Daily Trust about the victims’ last moments.

Muhammadu Sunusi Torankawa, the younger brother of Ibrahim Isa, who survived the attack, recalled their phone call. “He told me how he hid and watched as his men were dragged one by one and set on fire. He had already resigned himself to his fate, believing he would bleed to death.”

A grieving woman, Sadiya Sa’adu, also told the same newspaper that aside from her son, Haruna Hamidan, she also lost her brother and nephew to the same mob attack. She stressed that “they were not criminals; they were simply out to make an honest living.” She called on the authorities to ensure justice was served.

Vigilantes in Delta, Ekiti, and Oyo states have razed or forcibly emptied Fulani settlements, citing security concerns, according to several media reports. Fulani families have also reported widespread enforced disappearances of young men in their home states of Zamfara, Katsina, and Sokoto.

A senior police officer in Abuja stated, “While it is acknowledged that members of the Fulani group are involved in criminal activities, attributing every crime to Fulani herders oversimplifies the issue.”

Civil liberties are collapsing under the weight of stereotypes. Injustice breeds resentment, and resentment fuels radicalisation. When communities are punished collectively, even the innocent can be pushed toward extremism.

Understanding the roots of division

Dr Mudassiru Gado, a sociologist at Usmanu Danfodiyo University, explains how colonial indirect rule entrenched ethnic and religious divides. Today, the Fulani’s visibility in pastoralism and insecurity discourse makes them a target for collective punishment.

He links mob justice and vigilante violence to state failure, sensationalist media, and political opportunism. “In a climate of fear and mistrust, mob justice emerges as a socially sanctioned expression of communal vengeance and power contestation,” he said.

Structural inequities in land access, education, and representation only worsen the Fulani’s marginalisation. Gado calls for inclusive land reform, culturally responsive education, and full implementation of the National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP).

Subtle violence, deep scars

Even small encounters reveal deep prejudices. Abubakar Abdul-hamid Mobbo, a corps member undergoing the mandatory National Youth Service for young graduates from Niger State, recalled visiting the Kwara Ministry of Physical Planning. “When the official heard I was Fulani, she demanded I assure her that she was ‘safe’ before signing my logbook,” he said. “I could have retaliated, but I chose not to—she was an old woman.”

Across Nigeria, young people with dreadlocks or laptops are labelled fraudsters, women in unconventional dress are branded sex workers, and cross-dressers are accused of destroying African values. These judgments often justify police brutality, job discrimination, and even lynching.

Governor Soludo’s intervention invites a national reckoning. Citizens, leaders, and the media must work to break the circle of divisive narratives. Safety is not merely the absence of violence — it is the presence of truth, justice, and dignity.

The content addresses the pervasive issue of stereotyping and profiling based on ethnicity and religion in Nigeria, exemplified by stigmatization against women in hijabs, people with ethnic hairstyles, and the Fulani community. Profiling leads to harassment, fear, and violence, as Fulani herders are often blamed for crimes without evidence, and such narratives are perpetuated by media and politicians. Ethnic scapegoating is used politically to instill fear, with the media often reinforcing biases. The article calls for breaking these narratives through equitable policies and promoting justice and dignity as foundations for safety and unity.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter