‘We Are Still Displaced’: Resettled IDPs Describe Greater Risks At Resettlement Site

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) who have been resettled in Nguro Soye, Borno State, say their transfer to a new location has not improved their situation.

When Ya Inde Ali, 30, was resettled to Nguro Soye, a community in Bama Local Government Area (LGA) of Borno state, northeast Nigeria, she planned to put her money into farming. She acquired a piece of land and bought three cups of bean seeds and five cans of pesticide, hopeful for a successful cultivation.

On the day she went to till and spray her farmland, she was ambushed by members of an insurgent group who stole her seeds, pesticides, and farming tools. “I told them I just wanted to cultivate my land and they said I should go away,” Ya Inde said.

As part of the Borno state government’s plan to empower internally displaced persons (IDPs) who are being resettled in various resettlement camps in Borno, Babagana Zulum, the state governor, had promised to dole out cash assistance to IDPs after months of halted donations. Although many have not received this pay, Ya Inde did. But after her encounter with the insurgents, she was set back to square one.

Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe states in the Northeast have been the epicentre of the decade-long armed conflict and insurgency that has killed thousands of people, displacing many more who have fled their homes to seek refuge in relatively safer areas.

These IDPs who occupy camps and camp-like settings have been facing worsening humanitarian disasters. However, last year, the Borno state government began to shut down camps in Maiduguri, the state’s capital, resettling IDPs in areas the displaced persons insist insurgent groups still patrol.

According to Zulum, the reason for resettling IDPs is the prevalence of drugs and substance abuse in the camps, prostitution and child marriages, street begging, and growing dependency on donations.

IDPs who are in the process of being or have been resettled were promised financial support, safety, and security but many of them now living in various resettlement areas have described it as a ‘second displacement’ while being at risk of terror attacks.

Second displacement

Ya Inde, originally from Kodo, a community in Borno state, is one of the displaced women whose husbands were arbitrarily detained by state forces on allegations of being members of or having affiliations with Boko Haramseven years ago. She tells HumAngle how she left home in search of safety and ended up in Banki, a town bordering Cameroon. From Banki, they were separated from their husbands and taken to an IDP camp in Bama.

“Almost eight years now, I have not heard from him until recently when I heard he had been taken to Borno Maximum Prison from Giwa Barracks.” She said it ignited her hope and she began to look for a way to see him when she heard, again, that he had been returned to Giwa.

Ya Inde explained that her stay in Bama without her husband was dreadful due to the lack of food and lack of support. “My children and I became malnourished. It was very severe and we were transferred to Maiduguri where we got treated, but our situation remained the same,” she said, noting that when some of the men who had been arrested with her husband were released, she thought her husband would be among them but he was not.

Ya Inde is a mother of five. “I am the mother and the father, and sometimes I have to find manual labour before we are able to eat.” She tells HumAngle that the state government had given them bags of grains and a sum of ₦50,000 to sustain themselves when they were being resettled, but after two months of resettlement in Nguro Soye without means of livelihood, they have been plunged back into extreme hardship.

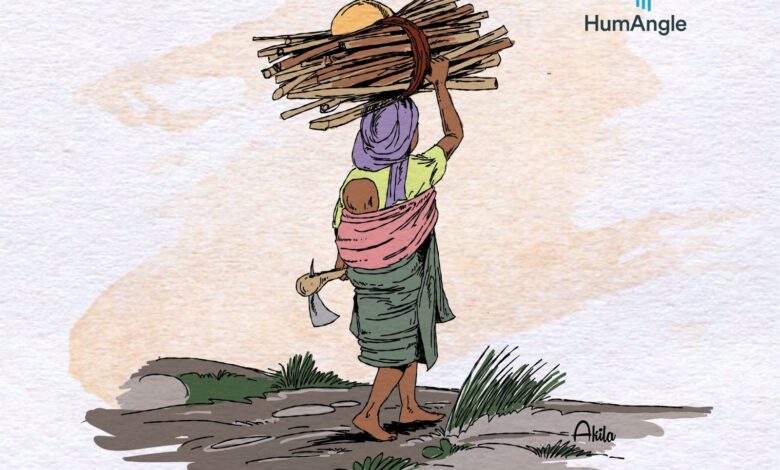

Apart from the lack of food, Dahiru Bulama, 33, originally from Kajere and now resettled in Nguro Soye says he still feels like a displaced person due to the lack of basic provisions. “No school for our children to attend, no hospitals, no water, no means of livelihood. Our women have to fetch firewood for sale before we are able to eat,” Bulama says.

He said that the state government had guaranteed they would be returned to their hometown. Instead, they have been kept in Nguro Soye where they are still regarded as IDPs and still live like IDPs. “When we came, we were not given a place to stay, we were just kept in a space they refer to as Bulabiri. I don’t know, is this where they would build a place for us or is this how we will continue living?”

Lack of water and sanitation hygiene facilities is forcing the resettled IDPs to resort to open defecation. Zara, 33, told HumAngle how they use polythene bags when they want to ease themselves, and this could exacerbate gender-based violence and the risk of infectious diseases, especially without clinics in the resettlement site.

“We can spend two days without water. Sometimes we contribute ₦20 each to fuel the generator that starts the pumping machine for water, but before we are able to fetch, the fuel has finished,” Zara said.

At risk of attack, recruitment

Women who find means through fetching firewood are exposed to being physically and sexually assaulted, abducted or even killed by the insurgent groups who are still in control of communities surrounding Nguro Soye. Hafsat Lawal, 40, told HumAngle that on several instances where she and other women went to collect firewood, they were ambushed by armed men, “We run away from them, but we do not get firewood.”

Resettled displaced persons also complained about the risk of being recruited by the insurgent group. Ya Inde noted that she has sons that go into the bush to fetch firewood or to work on farmlands owned by the town’s residents, “we are very close to Boko Haram. If our sons keep going near them, they could be drawn to them and get up one day and join them. Some can even be abducted.”

Heightened military presence in parts of Nguro Soye and other communities in Bama that are strongholds of insurgency means heightened military action in the areas. Zara noted that at the time of filing this report, they had no access to the spaces they usually collect firewood due to clashes between soldiers and the terror group.

“We have not had a chance to even get what we use to get food.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter