Visually Impaired Beggars in Nigeria’s Capital Suffer in the City’s Attempt to Hide the Poor

The clampdown on beggars in Nigeria’s capital city has left a vulnerable group displaced from the northwestern region by conflict in a dire situation. While the government says it plans to repatriate them, they vow to remain in the city rather than die by the guns of terrorists.

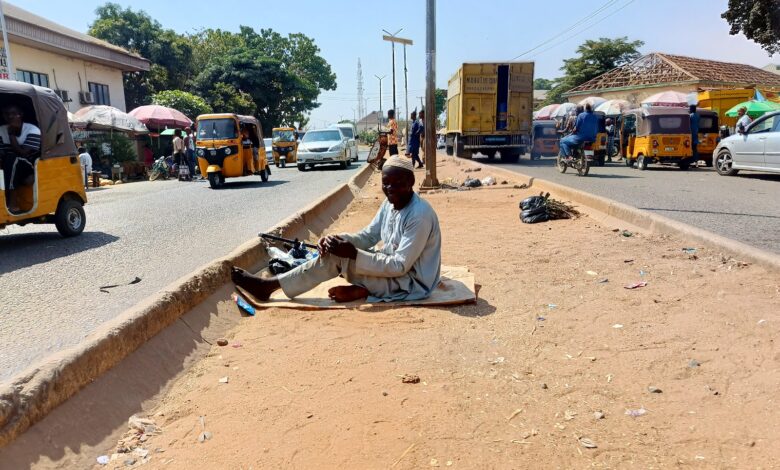

In the shadowy corners of the bustling streets of the Kado suburb in Abuja, Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT), where the hum of life rarely ceases, lie haunting echoes of displacement and despair.

Terrorism and insurgency have displaced countless across the country’s northwestern and northeastern regions, leaving an estimated 3.3 million, according to the United Nations.

For many of these individuals, survival has meant turning to begging in cities like Abuja. However, the situation has grown more dire; a recent government crackdown on street begging in the FCT has intensified the struggle of this vulnerable group, particularly those with disabilities.

Among them is 68-year-old Abdulrahman Yusuf, a visually impaired man whose life has been altered by violence and now that policy.

As the night sets in, Yusuf puts on his radio to listen to the news—one of his evening routines—before he rests for the day. It was through this medium that he first heard Nyesom Wike, FCT Minister, declare ‘war’ on beggars in the capital city.

Yusuf now spends his days confined to a small hut at the late Sarkin Makafi’s [the leader of the blind] residence in Kado, surviving on the kindness of neighbours. He recounted how he panicked upon hearing the news and pondered the thoughts of either running back home to insecurity by abandoning street begging or gambling on hopes—a decision he must quickly make. Yusuf no longer ventures out to beg, fearing arrest.

“Everyone wants to live in a peaceful environment,” he told HumAngle. “I would never leave my home in the first place if everything was fine and come here to suffer. We were forced to flee our homes by terrorists; we came here to seek refuge, and now we are asked to leave.”

Lives uprooted

Yusuf hails from Tsabare, a village in the Birnin Magaji Local Government Area of Zamfara State, north-west Nigeria, once known for its vibrant agriculture. Despite being visually impaired, he used to manage his farm with the help of his children and hired labourers.

However, the increased incursion of terrorists in Tsabare and, by extension, Zamfara State forced him and many others to flee their homes. Overnight, Yusuf was transformed from a farmer to a displaced beggar, stripped of his livelihood and community.

“If our hometown were peaceful, we would return immediately. Farming is all we know. But they [referring to the terrorists] won’t let us live—they seize crops, invade homes, and kill at will,” he said.

Terrorists have long preyed on rural communities in the region, turning it into a hotspot of violence since 2011. These armed groups hijack farmlands, displace residents, and perpetrate killings with impunity. Some communities, including Yusuf’s Tsabare, are now under the grip of these groups, where forced labour and fear have replaced normalcy.

Caught between terror and policy

Street begging is prohibited under FCT laws, with enforcement led by the Abuja Environmental Protection Board (AEPB). Successive FCT ministers have cited this prohibition to justify the forceful repatriation of beggars to their home states. However, Abba Hikima, a human rights lawyer and activist, told HumAngle that such actions violate citizens’ constitutional rights to freedom of movement and residence.

“There is no law that gives them the right to forcefully repatriate people,” he said. “This is a violation of both sections 34, 35, 41, and 42 of the Nigerian constitution [as amended].” He likened the policy to discrimination, where he said that “these vulnerable groups of Nigerians are targeted based on their disadvantage.”

Hikima has since filed a lawsuit against the FCT minister and four others.

“Since the minister instructed that we should not be seen on the streets, I don’t go out seeking alms anymore. It has been difficult living in such a situation. It’s only with the help of God and some of our neighbours here that we are surviving,” Yusuf said.

He is not alone. The widow of the late Sarkin Makafi, 50-year-old Balkisu Shuaibu, is also visually impaired. She echoed Yusuf’s concerns, lamenting the government’s failure to provide alternatives.

Since the crackdown, Balkisu’s survival has been difficult as they rely on food or donations from their neighbours.

“Where do they want us to go?” she asked. “I’ll gladly stop begging if I get some support to start a little business in the comfort of my hut. But I can never go back home because it’s not peaceful.”

“I am blind, and I can’t farm. Those who do not have any form of disability are not allowed to enjoy their gains; how then can we enjoy ours?” she added.

Her eldest son, Sirajo Shuaibu, explained that many beggars had fled the city out of fear of arrest. “Those who have alternative places to go to have all left the city due to fear of the unknown,” he said.

No beggars were in sight when HumAngle visited where Balkisu and other women sought alms around the Kado Fish Market axis.

‘At home, death is the only peaceful sleep’

The violence that drove these individuals from their homes shows no sign of abating. Yusuf recounted the horrors he left behind in Tsabare, including the murder of his in-laws and neighbour by armed terrorists. He takes long pauses as his face gleams with the pain echoing in his voice.

“They were killed by the same bullet. I can never forget that day,” he said. “If they know you have harvested your crops, they steal half of it and burn the remaining grains. How can we live in such an environment? There is no food, and you can’t do any business in your village.”

For 47-year-old Yusuf Sa’adatu, returning home is equally unthinkable. Even after she lost her niece to gunshots by terrorists, Sa’adatu couldn’t travel. Recently, she travelled to Tsabare to mourn a family member but was forced to flee again after another terrorist attack.

“I couldn’t spend three days there,” she recounted. “My neighbour and his son were attacked in their home and butchered with a cutlass. Before then, the terrorists had invaded their farmland and carted away with all their grains.”

“The only peaceful sleep you can enjoy in Tsabare community is death. You can’t sleep peacefully,” she said remorsefully.

When asked why she hasn’t taken any menial job and settled for begging, Sa’adatu said she got tired of searching because the response she received was that “I’m too old, and they prefer younger people for the job”.

Sirajo Shuaibu told HumAngle that Tsabare’s district head has been stripped of his authority and cannot perform his duties as the community leader without the explicit approval of the terrorists who have seized control. He described how the terrorists have assumed the role of mediators, settling disputes in the community in the absence of any state authority.

“People who have farmlands have no rights to their lands. They issue warnings to landowners. Those who defy them would face the consequences—the least is to be beaten to a stupor. People are being killed for farming on their ancestral lands.”

“In some instances, they push in their herds of cattle into people’s farmlands to destroy the crops, and nothing is being done about it. Those who revolted were either beaten or killed. You can’t fight someone yielding a gun,” he said.

A systemic failure

While experts condemn street begging in any form, they argue that displacement directly results from the government’s inability to create a safe environment for its citizens.

Yahuza Getso, a security and intelligence expert, observed that the initial displacement of these individuals underscores the government’s inability to provide adequate security and basic needs in crisis-affected regions. “Had the government fulfilled its responsibility to protect these communities, these individuals would not have had to leave their communities in the first place,” he said.

Getso further cautioned that the policy to clear beggars off the street of the FCT highlights the government’s failure to address the root causes of displacement effectively but risks creating further problems for the displaced population and the city itself. “Unscrupulous elements within the security forces can use this as an opportunity to exploit these displaced persons, making them easy targets for harassment and extortion,” he noted.

While weighing in on the potential consequences of relocating the displaced persons back to their original communities, Getso warned that forcing individuals to return to their communities without providing them with a sustainable livelihood could escalate tensions and breed more resentment.

When HumAngle sought clarification on the government’s plans for vulnerable people like Yusuf and Balkisu by reaching out to Peter Olumuji, the Secretary of FCT Authority Security Services’s Command and Control Centre, he asked us to send him a WhatsApp message. Since then, he has stopped answering phone calls.

For individuals like Yusuf, who are at risk of being displaced yet again, hope for a brighter future remains rooted in returning to their ancestral homes without being thrust into the hands of armed terrorists.

The article explores the plight of displaced individuals forced to beg in Abuja, Nigeria, due to terrorism in the northern regions.

The government's crackdown on street begging exacerbates their struggles, stripping people like Abdulrahman Yusuf of his livelihood and sense of security.

Human rights lawyer Abba Hikima argues such repatriations, conducted under the guise of legal prohibition, violate constitutional rights. The piece highlights the systemic failures that lead to displacement and criticizes the government's inability to address the root causes and provide alternatives or security for these vulnerable individuals, leaving them in dire conditions.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter