‘Unwrapped Lollipops:’ The Consequences Of Purity Culture Are Far Reaching For Women

In many communities, there is a huge emphasis on the need for women’s chastity, and not so much of it on men. But this disproportionate assignment of responsibily has far reaching consequences for women, from difficulty getting medical diagnosis to sexual violence. We spoke to women in Sudan and Nigeria.

Hiba Ahmad* didn’t need a lot of years to figure out that the purity culture she was raised in has been impacting her life in many ways. Growing up between Saudi Arabia and Sudan, this culture has been a major part of her life even though she was raised in a moderately religious home.

Purity culture, which is heavily attached to religious communities, is a practice that enforces sexual abstinence through educational programming. Despite the fact that this practice is supposed to safeguard the chastity of people in these communities, its impact has left many people, especially women fragmented.

According to Dr Sahar Wertheimer, a fertility expert and orthodox Jew, “the hesitancy to speak about certain aspects of women’s health because of modesty reasons, because of privacy reasons has hindered some of the basic knowledge that I think all women need to be better self-advocates, to take care of themselves, to take care of their loved ones and to make people feel less alone.”

“Being chaste was a huge highlight in my life growing up,” says Hiba. Even if my parents allowed us to be in the company of men, they were big on warning us. But it never felt like ‘don’t do this because Allah loves you,’ it was taboo and societal reasons that were the major culprit.”

At a point in her life, she had a 7 p.m. curfew for that reason but her brothers did not have the same restrictions. In purity culture, women are usually expected to shoulder the responsibility of keeping the community chaste.

When Hiba was 26 years old, she sought a diagnosis of what she believed to be Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), but the doctor refused to do a vaginal examination because of her assumed virginity. To make matters worse, her father, who was also a medical doctor, discouraged her from seeking more help.

“And years later, I discovered I wasn’t alone when I met a friend from Kenya who had similar experiences. Despite us coming from different cultural and religious backgrounds, we were both prevented from taking hormonal drugs to regulate our periods and suffered limitations in seeking help.” Learning this reality made Hiba realize how deeply purity culture impacts the lives of women all over the world.

“Back then, I was misinformed and didn’t understand that my body belonged to me.” But Hiba is still sceptical about seeking further help due to those experiences. She has been managing her condition by making lifestyle and dietary changes.

“My brothers didn’t face similar restrictions; the males in a patriarchal community aren’t scrutinized and in fact are free from all consequences. There is this common belief or understanding that a man can get away with anything just because he is a man.”

Even though this culture impacts both genders, for men the impact tends to be mostly in how it enforces an unrealistic view of masculinity and sexuality, but for women, the impact is all-encompassing; from what they wear, to how they should behave and even extends to being held responsible for the actions of the men around them.

Women raised under purity culture are usually compared with inanimate objects like expired milk, unwrapped lollipops, chewing gums, etc. This makes many feel devalued and dehumanized them.

However, a United States study published in 2009 shows that there is little difference in the sexual behaviour of teenagers who took a purity pledge and the sexual behaviour of teenagers who didn’t but those who pledged are less likely to take precautions during sexual activities.

Living In Fear

“The biggest impact in my life was when I was harassed and I was unable to seek refuge in my guardians because I immediately assumed they would punish me and this is relevant to all girls I know and have spoken to over the years.”

For many women raised in purity culture, they are placed on a pedestal and are punished for not maintaining that image whether it was consensual or not. And in cases of abuse or harassment, the burden is placed on the woman for tempting the abusers as a result of what she wore, what she did, and even what she didn’t do. This discourages girls and women that went through abuse to come out with their stories.

When Hiba joined the 2019 Sudanese revolution, she saw the way the women were dismissed for attempting to have awareness campaigns to empower women despite the fact that they were at the forefront of the protest.

“We would get told that this is not the time for it and often get attacked. Women were constantly being shut down and were at higher risk.”

Hiba believed that the Wahabism that was introduced to Sudan in the 80s brought purity culture with it. “A woman was flogged once for wearing jeans and even though we now wear them, we are to face consequences when we get caught.”

Purity culture divides women into categories of good and bad, where women society considers as ‘good women’ are rewarded and those considered ‘bad women’ are punished. For instance, when a ‘bad woman’ is abused, it is seen as a consequence of her actions; this division also leads to honor killings where women are killed by male family members when their actions are believed to bring dishonour to the family. The ‘immoral sexual’ actions that can lead to honour killings under purity culture may include openly conversing with men outside marriage, being a victim of rape, assault or having consensual sex outside marriage or even refusing to enter into an arranged marriage.

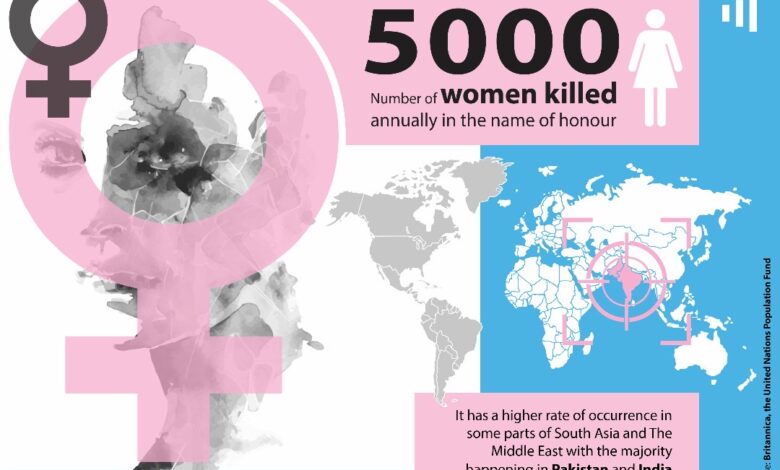

According to Britannica, the United Nations Population Fund made an estimate that 5,000 women are killed annually in the name of honour, and this crime is not limited to one specific faith or religion, even though it has a higher rate of occurrence in some parts of South Asia and The Middle East with the majority happening in Pakistan and India.

A New Dawn

“I want to say religion is free from the politicization that placed the unregulated patriarch in authority. The fact that purity culture is introduced to us through this religion that holds women in high regard is the failure of society.”

Hiba does not believe she has to let go of her beliefs in order to unlearn purity culture. She has found a way to coexist without the toxicity of the harmful beliefs she was raised with hanging over her head.

“It has detrimental effects on our society and on us individuals because in a world where women are not protected, everyone is in danger. We need to go back a couple of steps and instead of requiring chastity from women, we emphasize the importance of self, highlight how people can love themselves, give women the tools and support they need, educate everyone involved and enforce laws that serve to protect society. We have been in the dark for too long, dictated into misery and sentenced to suffering. If purity culture should do anything, it should go away.”

“I am now able to recognize my body and claim agency over it. It is a long way from where I was because I could not give it love the same way if I still exist in purity culture.”

The culture teaches women that their worth lies in their virginity and what is done to their bodies but by finding her worth in other things and unlearning that belief, 30-year-old Hiba was able to find peace and safety within herself.

As in Sudan, so in Nigeria

Halima Mason, a 29-year-old psychologist, holistic sex therapist in training, and the host of Spit and Swallow, a podcast aimed at normalizing and demystifying sex matters in Nigeria, was not raised in a strict purity culture. However, the elements of it in her life and her encounter with women raised in it as a result of her work opened her eyes to how harmful it is.

She also highlighted the punishment technique used to enforce the culture.

“There was a lot of slut shaming and fear-based teachings in terms of not getting pregnant or punishing students who were found kissing and making them seem like they’re so loose or bad. I remember even in Yoruba class, I learned about virginity and the white cloth and blood on the sheets being a sign of virtue after the first night and how some people would actually get chicken blood to put on the sheets if they didn’t bleed just so they were not disgraced or dishonoured, because the ‘first time’ wasn’t with their husbands. Which in itself is problematic because not everyone bleeds after their first penetrative sexual encounter and not everyone has a hymen; some get dissolved or get broken from other activities.”

Women in purity culture are often told that their virginity is a gift they can present to their husbands on their wedding night. And because of these harmful teachings, old beliefs on what constitutes virginity are still being maintained in order to police women’s bodies.

Several young girls HumAngle has spoken to who were sexually abused especially in conflict settings by insurgents and terrorists used words like ‘useless’ and ‘worthless’ to describe how they feel about having been ‘disvirgined’ before marriage. We noted that focus was given to that instead of the violation they had suffered.

Rape Culture

Halima explains that purity culture impacts rape culture and largely supports it.

“A singular pipeline I will draw is looking at how purity culture simply does not account for the bodily and sexual autonomy of the woman or the girl and when you do that without teaching boys consent or appropriate sexual behaviour, you are basically telling them that the women belongs to them,” she said.

“Purity culture condones all forms of male sexual behaviour and it starts from as little as using ‘boys will be boys’ to justify bad behaviour. This basically reinforces that their needs are more important than that of a woman. If you don’t teach consent, you teach all sexes that what the man thinks, says or wants is superior. He does not prioritize female pleasure or safety and can even go further to manipulate or be violent because his approval is seen as paramount.”

The conversation of assault or rape in purity culture shifts the scrutiny from the abuser to the victim, blaming them for what happened by asking what they were wearing or why they were around the abuser in the first place. This discourages a lot of girls and women from speaking out about their stories, according to Halima.

Long-term Effects

A big impact of purity culture that Halima sees in her work is vaginismus, which is a condition where women have challenges during penetrative sex: the vagina, more or less, clamps up to resist penetration and any attempts can be very painful. A lot of times that can be tied to psychological factors because there is the fear that if they have sex, then they are impure.

A 2021 study by Sheila Wray Gregoire, author and host of the Bare Marriage Podcast and other colleagues showed that 22.6 of 20,000 married Christian women reported vaginismus or another form of primary sexual dysfunction and after conducting one-on-one interviews with women, many of the participants reported cases of domestic violence with 43 per cent of the women believing that they are obligated to give sex to their husbands when they want it.

Halima emphasizes how purity culture also leads to gender identity issues due to the expectations of acting a specific way and the punishment and demonization that comes with acting outside of the norm.

“You also have an important bit which is the neglect of female pleasure. A lot of women do not take responsibility for their pleasure, not only that but their sexual health in general. You find people ashamed to talk about anything that has to do with sex. Sex is seen as a taboo so people won’t get tested for STIs, they won’t go on birth control or take charge of their sex lives…”

Purity culture affects sexual expression and body image. Sometimes it causes anxiety or even depression that is in relation to anything that has to do with sex and sexual behaviour.

“…It’s hard to undo this programming even after marriage (if it happens). They are afraid to explore or speak up when they have been harmed or abused or even when they’re suffering.”

Finding Healing

However, Halima believes that this culture can change with certain actions.

“The first thing is talking about it and normalizing conversations around sex and sexuality. We have a culture of being okay with being spoon-fed and not doing any research on our own or seeking out information. Reading, listening to podcasts, watching YouTube videos, and asking questions helps. Opening the mind first of all to different points of view, finding information, talking to trusted people, and talking with friends and family gradually peels back the layer of shame and taboo around these conversations.”

She also emphasized the need for psychological help for those who need it.

Sexual dysfunction that can arise from purity culture can cause sexual performance anxiety, genophobia or sexual disorders even within the limits allowed by society such as marriages, she says.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter