Untold Deaths, Tears Trail The Closure Of Abuja Arts And Craft Village

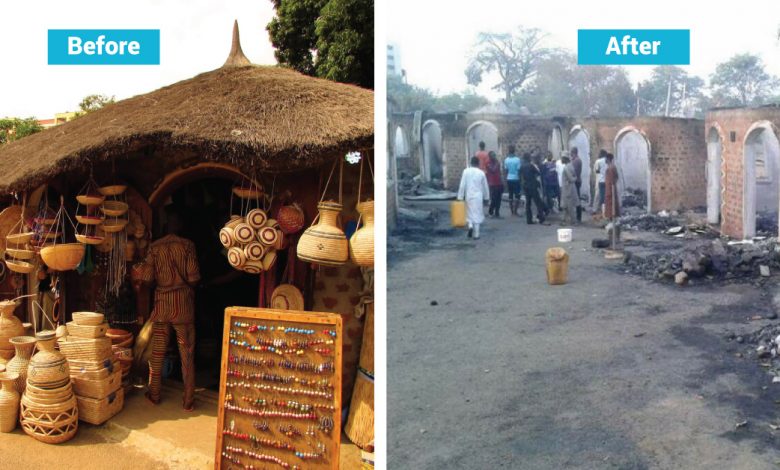

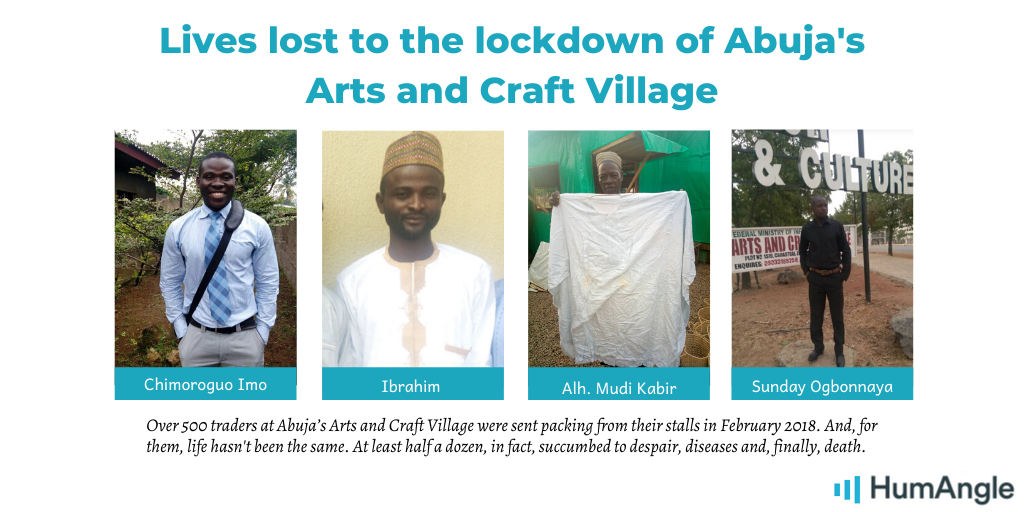

More than 500 traders at Abuja Arts and Craft Village were ejected from their shops in February 2018, their goods locked up and no alternatives provided. Having lost their source of livelihood, at least half a dozen have succumbed to despair, diseases and death.

Sunday Boniface Ogbonnaya, 31, was cheerful and easy going. He got along with other traders at the famous Arts and Craft Village, Abuja, where he managed two stalls with his cousin, regardless of their ethnic group.

Even while he was a student of Computer Science at Ebonyi State University, Ogbonnaya spent the holiday selling craft and cultural items in the market.

After serving in the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) scheme in November 2017, Ogbonnaya resumed at the market to support the family business and earn a living pending the time he would get a paid job.

About a year later, the National Council for Arts and Culture (NCAC) decided to close down the market and he started growing increasingly depressed.

He lost money, some of which was from loans, lost access to the shops, lost hope, and then lost his life.

It started with a mysterious fire incident in December 2017 that razed the bigger of his two shops with everything in it.

Thinking the situation could not get any worse, he quickly sought help from other traders and concentrated on the second shop.

Three months later, the Arts and Craft Village was shut under controversial circumstances based on the directive of the NCAC Director-General, Otunba Olusegun Runsewe.

“We thought it could be resolved in a matter of days,” recalls Festus Nwafor, Ogbonna’s cousin.

“We all went home. There was no alternative anywhere. No business. No money. No white-collar job. People were just living from hand to mouth.

“At a point, we all went to Jabi, Airport Junction Market. We pitched a makeshift tent but because we were new, we didn’t have customers.

“We were back to the same ordeal of no money, no business.”

Because of those challenges and the traumatising effect, Ogbonna started developing severe symptoms of High Blood Pressure.

Tossed from hospital to hospital

Sometime in May 2018, Nwafor said he discovered that Ogbonnaya’s phone could not be reached throughout the day.

Out of concern, he made his way to his house as soon as he closed from work.

On getting to the place he met Ogbonnaya lying on the floor, almost unconscious.

Immediately he called Ogbonnaya’s younger brother to the scene and together they moved to enable him to receive medical attention.

The time was 7 p.m.

First, they went to Wuse General Hospital but were turned back because there was no available bed to accommodate him.

From Wuse they proceeded to the Federal Medical Centre, Jabi where they were instructed to buy some drugs.

Then, the workers realised the department that could treat him was part of an ongoing strike and as such they could attend to him.

Immediately, they moved to Nisa Premier, a private hospital, also located in Jabi.

But the workers in Nisa Premier refused to admit him after examining him in the car and concluded that they could not handle his case.

By then Ogbonnaya was barely conscious and his blood pressure had risen to 200 /150, classified as hypertensive crisis.

When Nwafor took him to Nizamiye, another private hospital a little over 6km away, the hospital asked for a deposit of 300,000 naira to admit Ogbonnaya.

As Nwafor could not meet the demand, he moved to Limi Hospital but was told that the branch at Central Business District, did not treat heart-related problems. They also said that staff of the Garki branch, who could help, did not do night duty.

“We moved from there to Asokoro District Hospital,” Nwafor said, adding that by that time it was 5 a.m.

“They also told us the whole hospital was filled up and they didn’t have any bed space. But after we pleaded and told them we were desperate for any option available, they discussed among themselves and permitted us to manage a bed space by the reception.”

Nwafor said he paid for a list of prescribed drugs. Soon after, a test was conducted on Ogbonnaya and the result placed in a Compact disc.

There was only one problem: The expert who could interpret the content of the disc had gone home.

So they waited for hours and after the result of the tests came out Ogbonnaya was placed on a drip.

No further treatment was given to him until around 9 p.m., when he started breathing heavily, he said.

The nurses gathered and, “feigning seriousness”, brought all manner of items, manually compressed his chest, and supplied him artificial ventilation. But it was too late as Ogbonnaya died, Nwafor said.

He said Ogbonnaya was the only son among three children and that

his death shook his mother.

Nwafor thinks it was a miracle she survived because she was known to have serious health conditions.

“They must’ve told you about one guy they called Imoh,” Nwafor told HumAngle.

He continued, “He was an artist in the market. It was just last year somebody uploaded his picture and said he had died.

“There was one other guy called Muhammed. He recently died too. These guys mostly all died out of frustration and depression,” Nwafor said.

Kanayo Chukwumezie, who has been President of the African Arts and Cultural Heritage Association (AACHA), the sellers’ trade union, since 2011, said the problem started in 2010 when NCAC took over management of the property.

Before then, the Federal Capital Development Authority (FCDA) managed it.

After he took over as Director-General of NCAC in 2017, Olusegun Runsewe in February 2018 ordered the closure of the village on the allegation that firearms, drugs and stolen vehicles were found in the premises.

The order was in spite of a court injunction against the directive.

“I called a press conference challenging him to bring the proof,” he said.

“You say you saw 24 stolen vehicles, tell us where they are. You say you saw guns, tell us where they are and in what shops you saw them.

“Who have you prosecuted? Who were the vehicles traced to? Even from the chassis numbers, we can tell who owns them. You don’t just try to give a dog a bad name to hang it,” Chukwumezie said.

Chas Nwam, the Special Assistant to Runsewe, however, said the agency would not comment on the matter as some of the issues were in court.

Meanwhile, Chukwuemezie said the closure affected over 150 shops, over 500 traders as well as investments worth hundreds of millions of naira.

He said since the closure, many of the traders have returned to their villages, while others have tried to establish shops in different parts of Abuja.

But he stressed: “At the end of the day, whatever comes out of our struggle, we will know that we have exhausted all that is within our powers without fighting.

“Whether we win or lose in the matter is irrelevant, the record will show that there is a group that once fought to have this place to be what it is.

“Even if they remove it, they would say some people fought but did not succeed,” Chukwuemezie said.

‘Have they opened the market yet?’

Alhaji Mudi Kabir’s death was slow and distressing. Long before he died, he was already detached from the world ― no thanks to the shutdown of Art and Craft Village.

Eighty-something-year-old Baba Oja (the market’s father), as he was fondly called, moved to Abuja in 2000.

Before then, he sold cultural items at the famous Kurmi Market in Kano.

Auwal Suleiman, his close associate of over 30 years, recalls that they both set up shops at the Airport Junction Market before moving to the village in 2007 as part of the first set of vendors.

“When he heard that the market had been closed, the news shook him more than any other person,” Suleiman said.

“He had become accustomed to that market as if it was his own home.

The effect it had on him could have also been partly because of the number of people depending on him for survival, including two wives and 19 children in Kano.

Baba Oja was disoriented. He suddenly started acting irrationally and no amount of consolation from colleagues could help.

“Have they reopened the market yet?” he would ask at odd moments of silence or when unrelated matters were being discussed.

He was losing his mind. His health worsened over time and he had to retire to a hospital in Kano with the help of his family.

“When I went there to visit him, he could not recognise me even though I was standing right in front of him and we were the closest of friends,” Sulaiman recalled.

“He could not even mention my name because he was traumatised over what happened.

From there, things got worse until we heard that he passed away in the hospital.”

Sulaiman himself nearly lost everything.

He said he was distressed because after the closure some of his children quit school as he could not pay their fees.

Sulaiman said he sold some of his belongings and his wife’s to feed the family.

He said by the time he had access to his old shop, some of the items had been destroyed by rain.

Sulaiman said that he had moved to Airport Junction Market but was still not able to make ends meet.

He said it could take up to a week for him to make 1,000 naira unlike in the village when it was a daily routine. But he was happy he still worked closely with some traders in the same business.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

Detailed only that NCAC angle is scanty