Turning Grief Into A War Cry: The Women On The Frontline Against Boko Haram

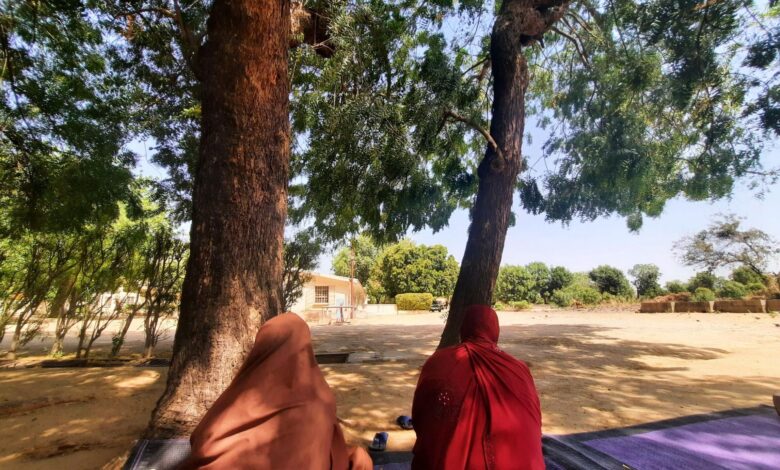

Though the war on terror in northeastern Nigeria is often pictured with a male face and baritone voice, a lot of women are also putting their lives on the line in the hopes of seeing peace return fully to the region.

Ever since Amina had to watch as her husband was killed, she’s made herself a thorn in the flesh of those responsible for his death, dedicating her life to making sure others do not suffer the same fate.

Mohammed had done nothing wrong. One morning in 2013, as he took his breakfast, Boko Haram terrorists stormed the couple’s house in the Gwange area of Maiduguri. They had been pursuing a young woman living in the neighbourhood who was an informant to the military and thought she must’ve entered the house.

Amina and her husband had no idea she had sneaked in and told the invaders no stranger was with them. So, when the terrorists looked around and found her, they became angry.

“Kill him,” Amina tearfully recalls one of them saying in Kanuri. Three gunshots followed. The bullets pierced Mohammed’s shoulder and chest. He was killed instantly.

That same year, as people picked up sticks across Maiduguri and formed vigilante groups with the aim of uprooting Boko Haram from their communities, Amina knew right away that she had to be a part of the movement. “I joined them to avenge my husband’s killing and defend my community,” she explains, her lips and eyes twitching in a way that bears testimony to underlying anguish.

Those vigilante groups later came to be known as the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) — or informally as ‘Yan Gora (stick-wielding people). Members work together with the Nigerian military to identify, arrest, and fight members of the terror group. They are also deployed to repel attacks. Because they were drawn directly from the affected communities, they acted passionately but also prudently, their involvement reducing the rates of arbitrary arrests by soldiers.

Since it erupted in 2009, the Boko Haram crisis has directly caused the death of at least 34,000 people and indirectly killed over 300,000 others. It has displaced millions of people, including over 343,000 Nigerians seeking refuge in neighbouring countries. What’s more, it has pushed over 8.4 million people into extreme lack and a life of dependency in the northeastern region.

The war against terrorism has wavered in effectiveness over the years as the insurgents continue to adapt to new strategies. Aside from the CJTF, another establishment that fills security gaps at the grassroots and in ungoverned spaces is the association of hunters. But unlike the CJTF, it is not open to just anyone. The privilege is inherited, passed from generation to generation. So it was the natural choice for Nawi, a hunter’s daughter, when she joined five years ago.

Her husband too was shot by Boko Haram in 2013, as he lounged in their front yard. She heard the gunshot from inside the house and was jolted by the sight of his lifeless body when she stepped out. She is not sure why he was killed. He was, after all, only a driver.

“Maybe they suspected that he may have a rapport with security officials or had made bad statements about them.”

Nawi is happy with her decision to become a hunter. Armed with a Dane or pump-action gun, she joins others in search of Boko Haram militants outside the metropolis and even in other local government areas. Sometimes, she’s joined by her two sons, who have taken an interest in security work too.

“I will do it for as long as I can till I get old,” she says. And that is likely many years down the line. The oldest female hunter she knows is at least 60 years old.

Women remain a minority in volunteer security outfits such as the CJTF. Amina says there are only two women in her sector compared to a total population of about 140 trained personnel. Across Maiduguri, she estimates that there are only 10 women out of about 800 trained officers. “Although members are primarily young men, women are also active in the group in many locations. The number of women members varies according to locality,” observes the Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC). “According to one man from Gwoza, over 10 per cent of ‘Yan gora members in Gwoza are women, whereas in Bama, it seems only some older women are members with younger women unable to participate.”

The scale is more balanced in the hunter association, where over 100 members are female out of an estimated population of about 800 in Maiduguri. The poor representation of women in security forces is reflected in government agencies too. The percentage of women in the police, for instance, has dropped gradually over the years, from 19.1 per cent in 2016 to 9.8 per cent two years later. The number of female officers also drops as they move up the ranks.

Like Amina and Nawi, there are other women who joined the security outfits because of personal grievances. Some were motivated to join after seeing fellow women in the forces. But the process is hardly smooth, especially for pioneers like Amina. Many people told her she was taking on a man’s job, but she resisted the pressure to give up, telling the naysayers that nothing would stop her from avenging her husband’s murder.

Living among many male officers and sleeping in the same space with them during operations is another challenge that came with the job. Everyone is treated the same way, but sometimes, women are allowed to sleep in the car while others use a makeshift shelter.

About eight years ago, the state government started paying Amina ₦15,000 ($33) monthly, just like other trained CJTF personnel. Then it later doubled the allowance. Nawi earns the same amount. The Economist reported in 2016 that only about 7 percent of CJTF’s troops were on the government’s payroll. The rest are considered volunteers. As of January, the government was said to be spending ₦150 million on monthly allowances for task force members, suggesting that only 5,000 people out of tens of thousands who contributed were rewarded. But those getting paid complain that the compensation is too little.

“It is not enough, but we just manage,” says Amina, who does not have another source of income. In spite of this, she has to take care of herself, her two daughters, and other relatives. Just this morning, she tells HumAngle, her children were sent out of school because they had not paid their fees. She has also not contacted her mother in several days because she has nothing to give her.

“Our request is for the government to review our salary because it is not enough to sustain us,” she appeals. “They are helping, but they should please do more, even if it’s with our children’s schooling. We are always buying things on credit to fend for ourselves.”

Apart from the financial distress, the job also takes a great toll on their mental health.

Amina has killed two Boko Haram militants since she joined the CJTF, and she still has not recovered from the experiences. She starts to cry again when she mentions this and uses the hem of her hijab to dry her cheeks. She had her first kill in 2016 when she went with military officers for an operation in Gudumbali in northern Borno, and then the second the following year when terrorists attacked Maiduguri from behind the Government Day Secondary School.

She says she has had access to a counselling programme, though, thanks to the government, and is now passing down what she learnt to junior officers.

Nawi says they receive all necessary support from local government agencies and traditional rulers, adding that she is respected by her male colleagues, who see how committed she is during operations. The people are another backbone of support.

“The villagers and farmers in the bush commend our efforts because we provide security for them to do their activities. They hail us and sometimes even give us water,” she tells HumAngle. They have killed many terrorists during such operations and have also arrested others. Some of the communities her work has taken her to include Baram Karawwa, Dikwa, Konduga, Mafa, Marte, Tamsuwu Ngamnduwa, and Tungushe.

“I feel very happy whenever we capture the Boko Haram members because they have terrorised people in the town and killed innocent people,” she says.

At the same time, she is saddened whenever she sees the conditions of women living with the insurgents. One time, less than two years ago, her team went to Nguro Soye for an operation and saw over a hundred women who were barely clothed.

“Kai, Allah. We really pitied the women when we rescued them because of the terrible condition they were in alongside their children. No proper dress. Some were even naked, barefooted and malnourished. You would find some women tying plastic bags around their bodies. They didn’t have what to wear. We are the ones who would provide clothes for them. Very pathetic. This has always bothered me when I think about it.”

Including women in field security operations helps to improve the effectiveness of counterinsurgency efforts. Amina explains that there are places only women can enter and some work they are better suited for, such as helping to frisk other women.

“While men accompany soldiers in their operations and conduct patrols of their locality, the roles of women in the ‘Yan gora include: interacting with other women, conducting body searches when required, screening women as they enter towns, and keeping an eye out for female ‘suicide’ bombers,” says CIVIC. The women also interview female suspects and informants, who tend to feel more comfortable around them. Those in vigilante and hunting groups famously take part in military operations alongside the men.

Amina urges other women to join the task force because it affords them an opportunity not only to protect themselves but the city they all cherish.

_______________________________

Ten years after the devastating incident at her Gwange home, Amina’s heart still aches whenever her mind flashes back to it. Mohammed had provided for the family from his earnings as a carpenter, but now she is a single mother waging a war against his killers while also fighting off the sharp blades of poverty.

It helps to know that the terrorists who pulled the trigger have met their end though. She knew who they were. They were people who lived in the same area. And when they entered their house, they had asked her to raise her head so that she saw them.

Months later, they returned to kill someone else, but the locals easily recognised them as ‘the same people who killed the carpenter’. So they alerted the military, who then gave chase and executed them.

All she wants now is for the war to end and for the terrorists to lay down their weapons and return home. Far too many children have become orphans and far too many women have been widowed by the crisis, she says. And for someone like her, she derives no pleasure in taking another person’s life — even if they’re Boko Haram members.

Nawi shares the same sentiments.

“My message to them [the terrorists] is they should embrace peace,” she says, her eyes locked on something far into the distance. “Nothing will happen to them. Before this incident, we were together with them. We are people of the same area, the same tribe, the same religion. If they surrender, we will go back to living together as we once did.”

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter

This blog has opened my eyes to new ideas and perspectives that I may not have considered before Thank you for broadening my horizons