Three Peace Accords Later, Tshobo and Bachama Still Clash in Adamawa

After several clashes that claimed many lives and property, two Adamawa tribes signed three peace accords in quick succession, but another attack has just happened.

It was December 23, 2025. A group of young men mounted motorcycles and rode through the warring communities of Lamurde Local Government Area in Adamawa State, northeastern Nigeria, to deliver the governor’s message. A peace accord had been signed, they announced, and all hostilities between the Bachama and Tshobo tribes had ceased.

“We don’t expect further damage. Enough is enough,” Ahmadu Fintiri, the state governor, said during the signing. “With this, I want to declare, there is no victor and no vanquish.”

In the days that followed, residents who had fled to neighbouring towns began returning home. Commercial farming, which had largely stopped after the July 2025 clashes between the two tribes, was slowly resuming after months of standstill.

Eager to resume work, Grace Joshua, a 35-year-old Tshobo woman based in Lamurde Town, and her group of friends secured a contract at a commercial rice farm on the outskirts of the town. On Jan. 3, they set out. But as they were about to commence work, a man appeared.

“We were all frightened, and we immediately stood up,” Grace told HumAngle, taking laboured breaths over the phone. The man, she said, was tall and dressed in black, wearing a mask.

“Two of us started running [to the opposite direction] towards Tingo Village, and then we saw two other men in front of us. That was when we realised that it was an ambush,” she recalled.

Gunshots broke out. Grace was hit in the thigh and fell to the ground, but the other woman reached the village unharmed. “I thought I was going to die until I saw people coming from my village, and that was how I was rescued,” she said.

By the time a rescue team arrived on the farm, the attackers had fled, leaving the other three women dead in a pool of their own blood. The villagers rushed Grace to a clinic for treatment, while the other women were buried that same day.

As Grace continues to receive treatment, the question echoes in her mind: when will the attacks cease?

The clashes

For centuries, the Tshobo and Bachama tribes coexisted peacefully, living side by side, sharing schools, markets, water sources, health centres, and even marriages. Situated barely a kilometre apart, both tribes fall under the same local government council, with most of the shared social infrastructure located in Lamurde Town, the local government headquarters.

However, this long-standing harmony was breached in July 2025, when a dispute over land ownership broke out. Locals say the farmland at the centre of the recent crisis is in Waduku and has been disputed for several years. The claimants — Mallam England Waduku, Afiniki Monday, and Engeti — are members of the same extended family, linked through intermarriage between the Tshobo and Bachama tribes. The violence reportedly began when members of the Engeti family, from the Tshobo tribe, went to work on the land, which they said was allocated to them through inheritance. Members of Mallam England’s family, from the Bachama tribe, confronted them and attempted to stop the farming, insisting that the land also belonged to them. What began as a family disagreement soon escalated into communal violence.

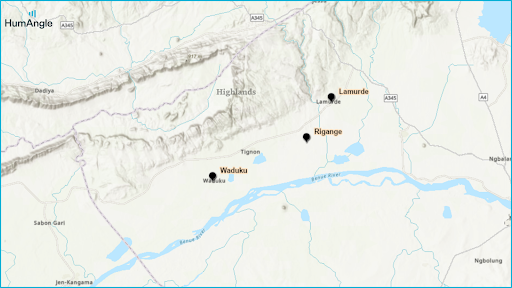

The Tshobo people primarily inhabit the mountainous areas of Lamurde Local Government Area, including communities such as Wammi, Lakan, and Sikori, which stretch toward the border with Gombe State. The Bachama, on the other hand, are largely settled in Rigange, Waduku, and other lowland communities. In towns such as Waduku and Lamurde, members of both tribes live side by side and often speak one another’s languages.

The violent land dispute has shattered daily life in these communities. Two months after the violence, HumAngle extensively documented the impact: some locals had fled to stay with relatives in other towns, while those who remained lamented being trapped within their communities, unable to move freely. Access to healthcare and other social services became difficult, especially for Tshobo communities, which had long depended on clinics in Lamurde town, a Bachama stronghold.

The crisis deepened communal divisions, as both tribes began avoiding routes and activities that previously brought them together, such as trading. By September 2025, social and economic ties were being severed. Despite several peace talks and reconciliation efforts by the government and stakeholders, both communities continued to clash.

In early December, both communities violently clashed again, prompting the intervention of the Nigerian Army. Tragically, the intervention resulted in casualties when the military allegedly opened fire on a group of Bachama women who had come out in Lamurde Town to protest the violence. Seven women and a man were killed, while many others sustained injuries. The Nigerian Army denied shooting protesters, but locals insist otherwise.

Hensley Audu, whose wife was killed in the protest, said his mind will never be at peace until justice is served. “Our house was burnt to the ground in Rigange, so we moved to Lamurde Town for safety, but then another incident broke out in the township in December, and my wife joined a group of women to protest peacefully on that day,” he said.

Hensley told HumAngle that he wasn’t at the protest ground, but eyewitnesses said it was the military who shot at his wife and the other women. “She was 63 years old. She left behind five children and two grandchildren,” he added.

While calm seems to have been restored in Lamurde Town, Hensley said locals no longer trust the military officials patrolling the area. “They were the ones who shot our women,” he stated.

He said his family has relied on support from relatives since his wife’s death.

“The government also came to check on us. They offered a token, but until the military takes responsibility and my wife gets justice, my mind will never be at rest,” he said.

The accords that keep failing

Since the conflict began, community leaders and residents have told HumAngle that the warring sides have signed three peace agreements, yet new clashes continue to erupt.

Hyginus Mangu, the leader of the Tshobo tribe, said that the first accord was signed in the office of the state’s Commissioner of Police when the clashes first broke out around July 2025, in the presence of all the state’s security heads. The other two, he said, were signed in the state governor’s office in September and December 2025.

“It was agreed that there would be interactions between the two communities. And it was unanimously signed like that without any argument,” Hyginus said.

Simon Kade, a Bachama stakeholder, corroborated the account. He noted that the accords were meant to bring a definitive end to the recurring clashes. However, with the recent attack on the Tshobo women, Hyginus said, the accord has been breached yet again.

To Hensley, the peace accord is just a piece of paper: “The government is not tackling the main issue. They need to arrest those who incite the conflict despite agreements to maintain peace.”

HumAngle learned that two suspects linked to the attack were arrested by security operatives and are now in custody.

Trading blames

Hensley accused some Tshobo youths of using social media to provoke hostility against the Bachama. Hyginus, on the other hand, blamed the Bachama for instilling fear among his people. He said Tshobo farmers who own land in Lamurde Town, Tingo, and other Bachama-dominated areas have yet to resume dry-season farming. Civil servants from Tshobo communities have also stayed away from the Lamurde secretariat, fearing attack.

Simon disputed this, claiming Tshobo residents around Tingo provoke Bachama people with insults, which he fears could spark renewed clashes. He added that Bachama residents living in Tshobo-dominated areas do not feel safe.

At night, Simon said, locals do not sleep despite the presence of security officials in the area. He explained that the community has set up its vigilante to patrol the area every night. Hyginus said the same situation exists in the communities where his subjects live.

Ready to embrace peace?

Wilson Ezra, who lost his wife in the Jan. 3 attack, said he feels hopeless without his wife, who left behind six young children. The last of them, he said, is barely a year old. “Even the other two women who died were breastfeeding mothers,” he told HumAngle.

While he grapples with the loss of his wife, he prays that more attacks do not happen in the future. “There is nothing I want in this life more than peace,” Wilson said.

The recent incident has sparked a new wave of displacement among both tribes. Residents are leaving communities such as Rigange and Waduku, which were significantly affected in previous clashes.

“We have left our home in Rigange and moved into Lamurde Town because we don’t know what might come next,” said Azurfa Morisson, a Bachama native from Rigange who lost her son in the December clash. Since the town houses the local government secretariat, she feels safer.

This displacement comes at a high cost for families like Azurfa’s, as they have abandoned their farmlands and businesses. But she is willing to do anything to stay alive.

Lamurde LGA is known for its rich cultural heritage, agricultural productivity, and trade. Before the violent conflict, locals across Adamawa and neighbouring states flocked to Tingo, home to one of the state’s largest markets. Recently, however, the area has become increasingly inaccessible. Roads leading to Lamurde Town, the Tingo market, and nearby villages are largely deserted. Business in Tingo is gradually coming to a standstill.

Simon, a commercial farmer who lost his home in one of the clashes, said economic activity has collapsed. “This situation has changed the market in Tingo. A lot of people used to bring their farm produce here, but as a result of this conflict, even the big trucks that come to buy and pack our goods and take them to other states have stopped coming,” he noted.

Hyginus, the leader of the Tshobo tribe, said they are ready to embrace peace. “There will be peace if today the Bachama’s will stop harassing, attacking, or provoking us, so that there’s a peaceful movement of people from my area, wherever they want to go,” he said.

He called on the government and the leadership of the Bwatiye Traditional Council, which comprises leaders of both tribes, to investigate the recurring incidents.

Simon argues that the Bachama tribe also want peace, but the Tshobo doesn’t want to let their guard down. “Everyone should hold on to what they own and stop trying to take over other people’s lands or property,” he said.

HumAngle reached out to the Adamawa State government for comments, but no response had been provided at the time of filing this report.

As both parties fail to maintain the fragile peace, many lives are strained.

In December 2025, Adamawa State's Bachama and Tshobo tribes signed a peace accord to end land dispute violence, but hostilities persist.

The conflict began over land ownership, disrupting community life and prompting retaliatory violence, leaving villages deserted and local markets inactive.

Despite signing three peace agreements, recent attacks, including one on Tshobo women, expose the fragility of the peace.

Residents are displaced, fearing violence and mistrust of security forces, particularly after a deadly protest incident involving the Army. Stakeholders from both tribes express a willingness for peace but accuse each other of instigating tensions and using provocative tactics. The community leaders urge government intervention for a thorough investigation to prevent further conflicts, as the local economy and social structures remain affected by ongoing tension.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter