Baba Jugudum was not there when his father was killed, but those who were there said the man died tragically.

Now, about 10 years later, he has begun to forget his father’s face. I watch as the realisation dawns on him when I ask what the man looked like. He seems thrown off by the fact, bowing his head to the floor where we are sitting and drawing lines on it with his index finger. At first, it looks like an attempt to conceal tears, but when he lifts his head, his eyes are dry as ever. It is not sadness, just shame.

“I can’t remember,” the 16-year-old says quietly, looking down again. He recalls the events of that day clearly, but his father’s face… it has begun to slip from him.

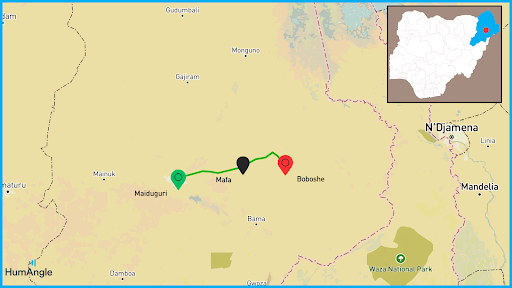

They lived in Boboshe, a village in northeastern Nigeria at the time, and the Boko Haram insurgency had begun to gain momentum. Villages in Borno State, the birthplace of the group, were falling to the terror group like flies, and those that remained intent on standing were besieged. The mission to topple democracy and impose “an Islamic state” where secular education was a sin and women were not to be seen was to be completed at all costs, including suicide bombing incidents, assassinations, and mass kidnappings of schoolchildren—all tactics the group used at the time.

It’s been nearly two decades since the conflict started, and though the mission has been largely unsuccessful, over 350,000 people have died for it, whether directly or indirectly, 25,000 others are missing, and children like Baba have had their lives upturned.

The insurgents took over Boboshe in 2014. They demanded grown men join them as combatants. But for those who refused, they demanded that they live in those villages under their rule as loyal subjects. Those rules were difficult: women could not go out, men were beaten and sometimes publicly executed if found to violate any “laws”, and nobody could go to school. As the situation got worse, the state government urged people trapped in these realities, through radio broadcasts, to have the courage to flee and make their way to Maiduguri, the capital city, where camps for internally displaced people had been set up. But anyone who attempted to flee and was caught by Boko Haram was branded a traitor and summarily executed. Many people risked this and tried to flee, but not Baba’s father.

“He used to say nothing could drive him away from his home,” Baba recalls.

But one day, armed men invaded their home and grabbed the man, saying an informant had told them that he was planning to escape with his family. They took him to another town where he was tortured and killed, Baba says. That day was the last time he ever saw his father.

“He was framed. My father used to say This is my home, even if the entire world spoils, this will still be my home. Someone lied against him. Those who were there said he tried to plead his case and explain that he was not planning to leave, but nobody listened to him. They held him for about a week… and then they killed him.”

Baba and his family tried to sneak out of town the night they learned he had been killed. They had gone a considerable distance when Boko Haram men caught them and took them back to the village. Perhaps because they were mostly children and women, they were not executed.

They tried again shortly after and were finally successful. They made it to Mafa Local Government Area (LGA) and stayed there for about a week, hoping to throw off anyone who might have gone after them. They successfully made it to state-controlled territories, where they were put up in several camps over several months before they made it to Maiduguri.

Now, he is no longer on the run. But despite his young age, his days are filled with thoughts of what to do for food. Sometimes he does menial jobs. Other times, he farms. Some days, he goes to the forests and cuts down trees for sale.

“If I don’t go into the forests to cut down trees to sell, I won’t have anything to eat for the day. And yet, if we go out, we run the risk of encountering Boko Haram. Sometimes, they demand your money. If you say you don’t have money, they might even kill you. But if we don’t risk it, we and our families will starve overnight and have nothing to eat.”

The risk of abduction for people who go in search of firewood has been notoriously high in the past few years. Several IDPs, especially those in the same camp as Baba, have reported abduction experiences to HumAngle in the past. Some were snatched right from the camp as they slept in their tents.

Beyond the economic hardship, however, there are other stark differences between what life was for Baba before Boko Haram and now. For example, he has memories of a communal kind of living before the insurgency, in a large family house with immediate and extended family members living nearby. That is no longer the case.

“I have not seen many relatives face-to-face in years. Many have died. Some have moved to Lagos. Others are inside town here in Maiduguri, and sometimes they visit,” he says.

His older brother, for example, lives in Lagos now, but things are not so rosy for him. He alternates between multiple jobs: a gateman today, a commercial motorcycle rider tomorrow.

This lack of familial proximity has rendered Baba’s life difficult and bleak. His mother, before the war, used to sell vegetables and farm produce. She was not rich, but she was comfortable. It also ensured a steady troop of neighbours visiting to buy things from her, such that the house was seldom ever quiet. Now, she cannot afford to sell farm produce anymore.

There is also the matter of education. Baba was enrolled in school before the war. Now, as a displaced person, he is no longer in school. He wants to become a doctor when he grows up. But for now, he remains out of school, hungry, and hopeful for a miracle.

Education has been a major casualty in the Boko Haram war, and authorities and individuals alike are aware and have made some efforts. Last year, UNICEF said it had trained 285,000 children orphaned by the Boko Haram insurgency and children of the vulnerable, in basic numeracy and literacy. The Borno State government itself has tried to bridge the gap through rehabilitating destroyed schools, building new ones, and implementing initiatives like The Learning Centre and interventions by UNICEF, the Qatar government, and several others.

On the other end of town

As Baba and his family were torn apart in Boboshe that day in 2014 after his father was captured and later executed, many other families were going through similar situations. In a different part of the village, another execution was going on, this time targeting a man who had been making arrangements to flee town with his family.

As Tala Adamu and his parents sat down to supper that day in their home, three men on a motorcycle, each masked and holding a gun, arrived at their compound. The armed men spoke very loudly, but it did not matter because Tala could not hear them. They were speaking a different language. As they entered the house, their mission seemed very simple. One of them pointed his gun at Tala’s father and shot him, killing him instantly. Then, the group got back on their motorcycle and went on their way, leaving Tala and his mother in shock.

The men were members of Boko Haram, and they had gotten word that the man was preparing to flee town with his family.

“Anyone who planned to escape from the village and got their plans exposed was immediately hunted down and killed by Boko Haram,” Tala tells HumAngle, corroborating many similar interviews. “That was what happened to my father. Many people were killed in this fashion. There were informants in the village.”

Later that day, villagers gathered and prepared his father’s remains for burial. As they hoisted his wrapped body on their shoulders after prayers and headed to the graveyard to bury him, Tala hung back at home.

“I was not allowed to go because I was just a kid,” he said. He was only about 9 at the time, by his calculations.

The following night, using darkness as a cover, he and his mother gathered what they could of their belongings and fled Boboshe for Dikwa. He believes they would have been killed if they were caught, but the brutal killing of his father the day before had shaken them so badly that they were willing to take the chance for escape. Dikwa was not entirely safe, but it was one step closer to the capital city, and so it would have to do. It had begun to serve as some sort of transit centre for people fleeing.

They made it to Maiduguri after several days and were set up in an IDP camp. A year later, still struggling to get used to life as a displaced child, Tala’s mother came down with cholera. Though she was rushed to the hospital when things deteriorated, she did not survive the illness. In the blink of an eye, Tala became all alone in the world.

He says that since he was just a kid at the time of his father’s death, he had not been able to learn any trade or skill from the man. This has made living hard for him, even now at 20. He spends all his time alone, has no friends, and does not go to school. He squats with the camp’s security guards; they let him sleep in their tent.

Tala is a young man of few words. His eyes seem devoid of life, and he struggles to keep them on people for long. He prefers to focus them far into the distance, on nearby objects, or on the floor. He looks anywhere but at me.

When asked what he would have wanted to be when he grew up if he had his way, he seems unable to understand that that choice, even in the imagination, is possible.

“What do you mean?” he asks. “If you had access to education,” I say, “And you went to the university and got a degree and started working. What work would you be doing?”

He is silent for a long time.

“Whatever God sees fit,” he says, finally. When pressed further, he says he would like to be a teacher.

***

For many people who go through these traumatic experiences as children, the memories fall away as the years pass by. But not for Modu Hassan, another displaced boy whose father was killed in the same year as Tala and Baba.

“I remember everything,” says Modu, now 18.

After weeks of enduring Boko Haram rule and the anxiety that came with it, his family decided to flee. They knew how dangerous it was, however, and therefore engaged the services of a man known simply as Abubakar. Abubakar was a courier who seemed to know the safest routes for people to escape and had accompanied a number of people to safety.

They travelled with him, all hoisting their luggage on their heads and trying to sneak out of the village that night. They had gone as far as where buildings ended and the bushes started. Unknown to them, armed men were hiding behind the tall bushes and trees, observing as they snaked through the forests. Suddenly, they emerged from their hiding spots and intercepted them.

“They collected our water, food, valuables, everything. They left us, the women and children, like that. Then, they took our father and Abubakar. They killed them both.”

Modu was 8 or 7 at the time. “They said spilling the blood of those seeking to escape was a religious obligation upon them,” he recalls.

He remembers his father as an exceptionally kind man. He took care of his family. “Everyone loved him. He was charismatic. In almost every nearby village, there were people who knew him.”

Things had not been peaceful before that day. They had been held under siege by the terror group for a while. And so even now, he struggles to think back to a time in his life when he knew peace.

He misses his friends: Baba and Kadi. His best friend’s father escaped successfully that year, but the friend was abducted by Boko Haram and is stuck with them to this day. They say he fights for them now. Modu believes if he had not gotten out when he did, the same fate may have befallen him.

“This was what my father was trying to avoid for me and my siblings. But Allah did not destine his safe migration. Only ours.”

Children have often been considered a valuable fodder of potential soldiers for terror groups operating in Africa. UNICEF said in 2021 that it had verified at least 21,000 child soldiers since 2016 in West and Central Africa alone. More than 3,500 of those were recruited through abduction. In Nigeria, specifically, over 8,000 boys and girls had been recruited as child soldiers since 2009, according to a 2022 report.

Modu does not think his best friend would ever return, even if he had an opportunity to do so. “Many people have returned, but not him. If he wanted to, he would have, because even his siblings found a way out. He has been radicalised.”

Modu’s mother has not quite remained the same since. She cries often, wanders aimlessly, and speaks of her husband all the time. Not too long ago, she ran into Boko Haram as she went in search of firewood. Luckily, she was a safe distance away by the time she realised.

Modu is grateful to have made it out alive, but his life now is filled with problems. Young as he is, he farms, does menial jobs for people whenever possible, and spends his time roaming about the camp. While he used to go to school before Boko Haram, that is no longer possible. He would have loved to become a police officer.

It is a common fate he shares with thousands of children in Borno State, including Tala and Baba. Boko Haram may not have succeeded in toppling Nigeria’s democracy. But it has succeeded in keeping thousands of people out of school: potential doctors, teachers, and police officers.

Baba Jugudum, along with other children like Tala Adamu and Modu Hassan, has faced severe hardships due to the Boko Haram insurgency in northeastern Nigeria.

Ten years after Baba's father was tragically killed for allegedly planning to escape, Baba and his family managed to flee their village, Boboshe, to seek refuge in Maiduguri. Despite now living in relative safety, Baba's life is fraught with difficulties like food insecurity and the risk of Boko Haram encounters, and he cannot pursue his dream of becoming a doctor.

Tala and Modu experienced similar tragic events, with their fathers killed in efforts to escape the insurgency. Tala, who lost both parents in quick succession, struggles with a solitary life without education, while Modu remembers his father fondly and grapples with the harsh realities of living without peace.

Education remains a significant casualty of the conflict, with countless children deprived of schooling, shaping a bleak future for many potential professionals in the region despite some governmental and non-governmental educational interventions.

Support Our Journalism

There are millions of ordinary people affected by conflict in Africa whose stories are missing in the mainstream media. HumAngle is determined to tell those challenging and under-reported stories, hoping that the people impacted by these conflicts will find the safety and security they deserve.

To ensure that we continue to provide public service coverage, we have a small favour to ask you. We want you to be part of our journalistic endeavour by contributing a token to us.

Your donation will further promote a robust, free, and independent media.

Donate HereStay Closer To The Stories That Matter